The 1966 Division Street Uprising & the Puerto Rican community in Chicago

In 1966, Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley declared that the first week of June would be known as “Puerto Rican Week,” culminating in the first Puerto Rican Parade, to honor the growing Puerto Rican population in the city. After the parade, while people were still celebrating, police shot a Puerto Rican man in the leg, following a pattern of police violence against the Puerto Rican community, which sparked a three-day uprising in the Humboldt Park neighborhood that changed Puerto Rican history in Chicago.

Joining me to help us understand the Puerto Rican community in Chicago both before and after the Division Street uprising is Dr. Mirelsie Velázquez, an associate professor of education at the University of Oklahoma and author of Puerto Rican Chicago: Schooling the City, 1940-1977.

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The mid-episode audio is “Quiero Vivir en Puerto Rico,” performed by Marta Romero and Anibal Herrero y Su Orquesta, and written by Guillermo Venegas (Hijo). The audio is in the public domain and is available via the Internet Archive.

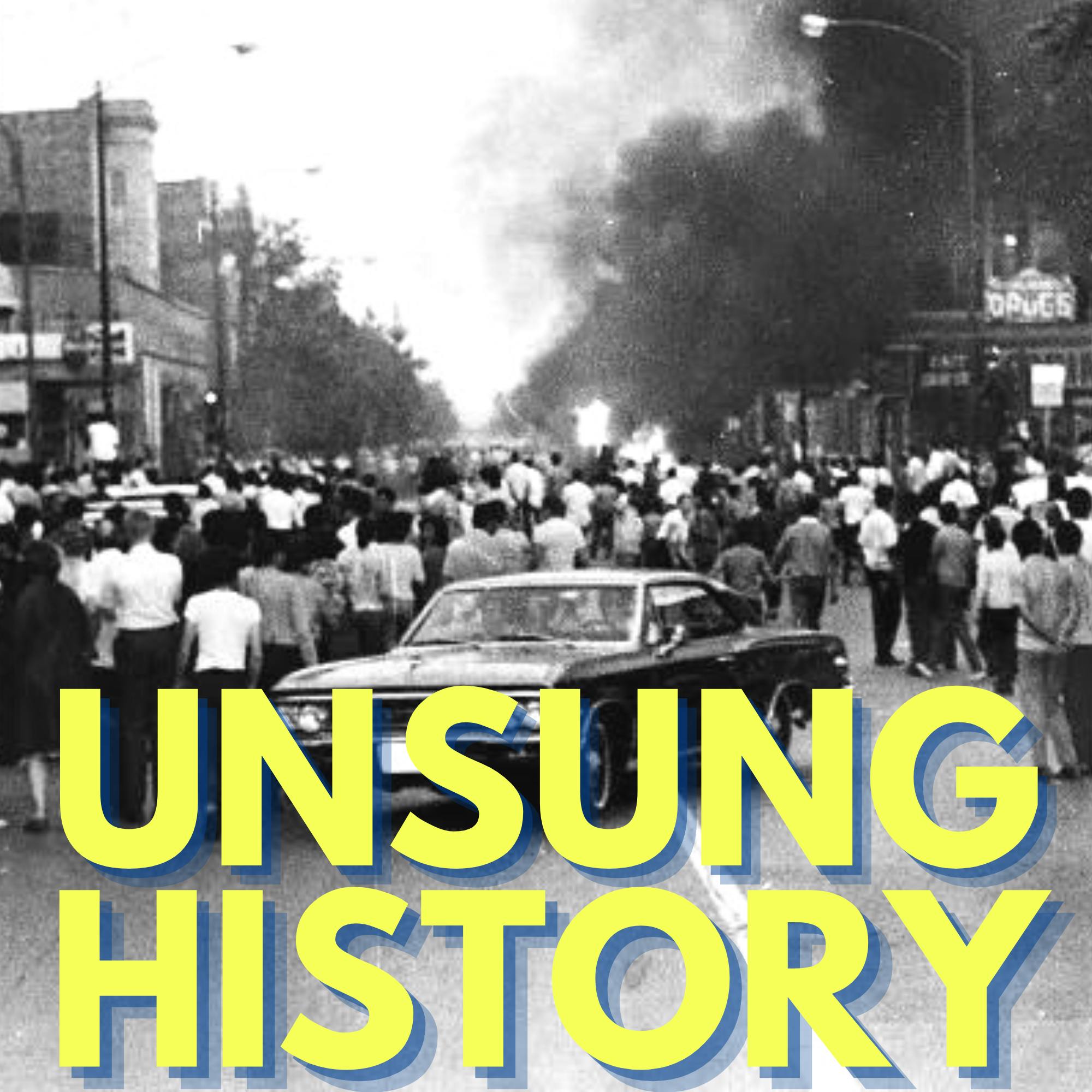

The episode image is “June 12 1966: Smoke rises from burning squad car as a crowd surrounds it during riots in Humboldt Park,” from the 1960s: Days of Rage website.

Additional Sources:

- “It Was a Rebellion: Chicago’s Puerto Rican Community in 1966,” Chicago History Museum, via Google Arts & Culture.

- “Chicago's 1966 Division Street Riot,” by Daniel Hautzinger, WTTW, September 2, 2020.

- "Recollections: 1966 Division Street Riot," by Mervin Méndez, Diálogo: Vol. 2 (1997): No. 1 , Article 6.

- “Puerto Ricans Riots: Chicago 1966,” Center for Puerto Rican Studies, CUNY Hunter.

- “Spanish-American War,” History.com

- “1917: Jones-Shafroth Act,” Library of Congress.

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Kelly Therese Pollock 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app, so you never miss an episode. And please, tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen too. On today's episode, we're discussing the Puerto Rican community in Chicago, and the 1966 Division Street uprising, the first uprising in the country attributed to Puerto Ricans. In 1898, the United States inserted itself into the Cuban struggle for independence from Spain, launching the Spanish American War. The war was brief, with the United States quickly declaring victory. On December 10, 1898, the Treaty of Paris formally ended the war. In this treaty, Spain gave up its claim to Cuba and ceded Puerto Rico and Guam to the United States. In the same treaty, Spain transferred control of the Philippines to the United States for $20 million, as we discussed previously, in our episode on Filipino nurses. In March of 1917, President Woodrow Wilson signed the Jones Shafroth Act, commonly referred to as the Jones Act. This act granted United States citizenship to Puerto Ricans. It also separated Puerto Rico's government into executive, judicial and legislative branches, with the legislative branch split into a bicameral legislature. During the 1920s, around 42,000 Puerto Ricans, now with US citizenship migrated to the US mainland, mostly moving to New York State. After World War II, Puerto Ricans began to move to the US mainland in larger numbers. By 1960, 32,000 Puerto Ricans had settled in Chicago, with a large community living near Humboldt Park on the northwest side. Most of the Puerto Rican population in the city worked in low paying jobs in factories, or in the service industry, having been recruited to the city by employment agencies. In 1966, Mayor Richard J. Daley, declared that the first week of June would be known as Puerto Rican week, culminating in the first Puerto Rican parade. The parade was held on State Street, downtown on June 11, 1966. Until 1957, it had been a felony in the United States to display a Puerto Rican flag. So the site of hundreds of Puerto Rican flags along the parade route was historic. On June 12, police, who were possibly responding to a call about a fight, chased two Puerto Rican men and shot one of them, 20 year old Arcelis Cruz in the leg, near the intersection of Damon Avenue and Division Street. Chicago police patrolman Thomas Munyon claimed that Cruz had drawn a gun. Some witnesses claimed otherwise. The shooting was only the latest in a pattern of police brutality against Puerto Ricans, and it sparked an uprising against police violence in the neighborhood, involving over 1000 participants and hundreds more onlookers. Local radio stations covered the event in real time, including a Spanish language radio host named Carlos Agrelot. That coverage attracted more people to come to the neighborhood to join in. As more police were called into the area, a police dog bit a Puerto Rican man in the leg, which intensified the fighting. The crowd attacked the police officers with rocks and bottles, and to overturn and set fire to police cars.

The next evening there was again violence along Division Street, including looting. The police responded in force, and shot seven people. Community leaders who recognized that the police presence was making things worse, asked them to leave; and the police department did ask the officers to de-escalate. There was a brief peace during a 3000 person rally in Humboldt Park, organized by community organization leaders and clergymen. But after the rally, there was more rioting, and the police returned, again fanning the flames as they beat the protesters with clubs and fired shots. On the third and final night of the uprising, Chicago police sent 500 officers to patrol the area. Although less violent than the West Side riots in Chicago later in 1966, during the three nights of the Division Street uprising, 16 people were injured and 50 buildings were seriously damaged. The uprising lasted three days, but the impact lived on. In many ways the event was a turning point in the history of Puerto Ricans in Chicago, waking up the city to the issues facing the community. A few weeks later, on June 28, over 200 people marched from Division Street to City Hall, a five mile trek to protest police brutality. Following that, the Chicago Commission on Human Relations held hearings at which Puerto Rican residents discussed the challenges they faced, including not just police violence, but also housing discrimination and poor educational opportunities, and they proposed policy solutions. The city established a Division Street office in order to better track and respond to the needs of the community. The Puerto Rican community itself was inspired to create several organizations, including the Spanish Action Committee of Chicago, SACC, and the Latin American Defense Organization, LADO. In 1977, the Puerto Rican community again clashed with the Chicago Police Department in the Humboldt Park riot. Today, there are around 100,000 people of Puerto Rican descent in Chicago. Chicago is the US city with the third largest population of people of Puerto Rican descent, after New York and Philadelphia. The Humboldt Park Paseo Boricua neighborhood continues to be home to the Puerto Rican community, with the largest concentration of Puerto Ricans in the Midwest living there. Puerto Rico itself is still an unincorporated territory of the United States. Various pushes for either independence or statehood have not yet come to fruition. Residents of Puerto Rico are United States citizens, but cannot vote in US presidential elections and have no voting representation in the US Congress. In the most recent non binding statehood referendum during the November, 2020 elections, 52% of Puerto Ricans answered "yes" to the question, "Should Puerto Rico be admitted immediately into the Union as a state?" HR 1522, The Puerto Rico Statehood Admission Act, was introduced into Congress by Representative Darren Soto of Florida in March, 2021. It has not received a vote. Joining me to help us understand the Puerto Rican community in Chicago, both before and after the Division Street uprising is Dr. Mirelsie Velazquez, an associate Professor of Education at the University of Oklahoma, and the author of, "Puerto Rican Chicago: Schooling the City, 1940-1977."

Thanks so much for joining me today.

Dr. Mirelsie Velazquez 10:06

No, thanks for having me.

Kelly Therese Pollock 10:07

Yeah, I love anything to do with Chicago history, and this was a piece of Chicago history I didn't know, so I'm thrilled to have learned about it. So I wanted to start by asking how you got interested in this topic. I know that your book is part of a larger series on Latinos in the Midwest, which I think is not what people think of when they think of Latinos. So I'm interested in how you got interested in this sort of broader topic, but then the specific topic of your book.

Dr. Mirelsie Velazquez 10:36

You know, the easiest response to that is, you know, I grew up in Chicago. My family migrated to Chicago, you know, in, I won't, I won't say the date, the year, I won't out myself; but they migrated to Chicago, and I kind of walked into history without realizing that I was walking into history as a child, you know. And so me, you know, writing about the history of Puerto Ricans in the city and using schools as a way to have that conversation was really inspired, or at least framed around my own experience with schooling as someone that walked into a space that not only did I not know what I had walked into as a child, but didn't understand what I inherited, as a student in those spaces. So I write about the very community that I moved into, as a almost five year old, right, you know, monolingual speaker coming, you know, coming into the city. And so I can't separate my separate my own history in relationship to the space to the work that I do. And so it was never supposed to be, you know, this lifelong project. It was supposed to be something that I was going to write about for just a little bit of, you know, a small moment. And then it's, it's become part of my identity in a lot of different ways. So here I go walking into it, because it was part of my identity. But now the work itself has become part of who I am, and a sense of responsibility. And so Chicago offers, you know, so many of us that opportunity to kind of engage with our own familial and community histories and write us into or at least pull us out of the footnote of history, like my community itself.

Kelly Therese Pollock 12:04

Yeah. And so in your book, you're looking specifically at 1940 to 1977. So can we talk about sort of what what bookends that why that is the period of time?

Dr. Mirelsie Velazquez 12:16

And there are bookends, right? And so when I think about those years, I think about how they situate the history of the community in a very particular way. In 1940, you start seeing the migration through the city, in small numbers, you know, and kind of moving into the 50s and 60s, it intensifies. And then 1977, you know, there's two reasons why, and then '77, one of them being that it's the second community uprising that happens in the Puerto Rican community in 1977. And so everything that's happened, you know, from 1940 to 1977, tell us a story of a community that was not just waiting for things to happen for them, but working toward creating change, right. I also ended in 1977, because I enter history a few years right after that. And so there's something to be said about not wanting to be, I don't know, not wanting to kind of be biased in the way in which I was writing this historical narrative, right. So I enter history right after that. So '77 really is a reminder to the city that the Puerto Rican community has been present at that point for three decades, and very little change has happened. And so then what happens after '77, it's a conversation that people are starting to write about a little more. And I think it's something that eventually I'll probably pick up a little more in terms of what's going on there. But '77 really does signal to the, to the city, but then also the community itself, that what's been happening hasn't worked. And so now we have to move from, you know, mobilizing on the streets to then becoming a political force in the city. And we start seeing people move into political office in the city, Puerto Ricans moving into political office after 1977 in larger numbers. And I think, you know, we have to have a conversation about what led us to that point. And I think '77 is a good space to have a very intentional conversation about knowing that whatever, whatever has been going on isn't working, and we're just not sure what's going to work for us.

Kelly Therese Pollock 14:12

Yeah, so I wanted to talk some about your sources as well. And so, in you talk about this in the book that the earlier sources, it's difficult because often it is the Puerto Rican community being written about, but it is not necessarily their voices coming out. And that becomes a little bit easier as they become as they start to have their own print media sources, multiple sources. So I wonder if you could talk through what you're looking at during this time period to figure out what what is going on here.

Dr. Mirelsie Velazquez 14:43

You know, and, and it becomes this obsession right for me in terms of what does it mean to move our you know, voices and people like literally people out of the footnotes of history? What does it mean to be constantly living in other people's memories right and other people writing about the community, writing about individuals? And we already know that decisions are being made about the community without their consent and without their voice, especially early on in the 1940s, '50s, and early '60s. But the documents support that and tell us that right. And so, you know, really what was available to me and for other folks that are writing about Puerto Ricans in Chicago from the same time period, obviously, using a different lens is that most of the documents are coming and materials are coming from from the agencies, right city government documents, memos, you know, that probably were never meant to be seen by anybody. Right. And so when they're having a conversation and calling Puerto Rican women, the best import that the island has to offer, right, and this is written by city officials, nobody was meant to see that right? Or maybe they didn't care who saw it, right? Because we're talking about a community that's historically has been marginalized. Right? And And history shows us that and contemporary conversations actually show us that if we look at what's happening across the archipelago right now. And so what does it mean for someone like me, that that has a connection to the community, and this is my history that I'm writing about, to then be in the archives and seeing these things written about, about us, about our bodies, about the, you know, interesting ways that the city was trying to come up to deport people who were US citizens, right? Because these are the conversations that are happening, you know, let's not make you know, Chicago an appealing option for them, you know, because then what are we going to do with them once they're here, right? And so these documents are coming from city officials who are writing policies, who are framing the opportunities and the resources that are going to be available to the community without their consent, and without their knowledge. Once in a while, you'll you know, you will come across, you know, documents and materials that signal a little bit of hope, too, you know, in terms of people that were going to use their positionality to provide resources and opportunities, especially around schooling for the community. But those are very few, right, and so, you know, that's what the '40s and '50s look like, you know, for any of us that are doing work on the community, that the materials that are available, are written by people who are perpetuating harm in our community, whether they know that they're doing it or not, you know, who's to say? But it's just what's what's going to happen to the community? The hope comes from what happens in the '60s and '70s, where the community itself is writing under their own terms, and creating newspapers and creating journals, and creating, you know, community based organizations that then invite them into the writing of their own narratives, their own history.

Kelly Therese Pollock 17:35

So you focus on education. So can we talk some about why why that is your focus, but also the sort of lens that gives us into the larger community and what is happening?

Dr. Mirelsie Velazquez 17:48

You know, as I told my, my students, you know, those who I'm training to do some engage in historical research themselves, is that there's two ways that you can really understand how communities build community and engage with one another right, in order to understand the social processes that go into, especially for marginalized and racialized communities to build community themselves, right? And it's either churches, religion, right, or schools. I don't write about religion, I don't write about church or religious organizations. And so schools gave me a platform and a way for me to engage in conversation about what happens once the community starts migrating to the city right to labor migration, initially, not all of it. And so then how is it that then they start reimagining the city as the place for themselves, right, that their families are going to come and join them, their children are going to attend schools, right. And so schools become an opportunity for people to reimagine a future for themselves, right. But then also as a way, for them to be reminded just how little investment there is in their their humanity in those spaces, because schools, for many of us are the first place that we understand our identities. And I don't mean that in a good way. I mean it in the way in which we enter schools, understanding that these aren't places for us, that they're not places that are going to inform our day to day experiences under our own terms, right. We don't see ourselves written into histories in a lot of different ways. And so schools for Puerto Ricans, where education will formally and informally right, become a place where they start negotiating their positionality within the cities, right? Moreso, it also becomes a place ,schooling in general becomes a way for Puerto Rican women to start moving out of the domestic sphere, right and start moving into roles as not just community activists, but educators themselves, right. And so Puerto Rican women utilize education and schooling as a way to navigate the city. And then also to think about the ways in which they want to be informed, but also inform the future for the community in very interesting ways.

Kelly Therese Pollock 20:01

Can you talk some about, you talk about this in the book, the the education system that was in place in Puerto Rico that they were coming from, was already an American system because it was already part of the colonialism? And then they come to Chicago. And yet Chicago can't seem to figure out how to educate students who are already coming from an American education system. So what did that transition look like? And seems like there's a number of places where there's sort of misunderstandings, miscommunications, or willful ignorance on how to best help these students.

Dr. Mirelsie Velazquez 20:38

Willful willful ignorance, right? You know, Sonia Nieto tells us that Puerto Ricans have been in US schools since 1898. Right since occupation in 1898. And the first thing that or two things that the US government did, once they occupied Puerto Rico, beginning in the, in the late 1890s, was to transform education. Right, but then also the military. And this is before citizenship becomes part of the conversation, right? And so, before they even talk about what these bodies are going to mean themselves, they think about how those people, you know, across the archipelago are going to best serve the Empire, right? And so if you want to convince a population of people, to, in some ways, kind of buy into the system that's being imposed on them, then schools become part of that conversation, right. And so Puerto Rican children, then become infused with the responsibility of what Puerto Rico is going to mean, right, in turn, under American ideals, right under, you know, US ideologies. And so Puerto Rican children are expected to start learning English, Puerto Rican children are expected to engage in patriotic exercises, right learning, patriotic music, learning American history, in ways that people argued were better informed than what you, you know, students in the United States were engaging, right. And so this becomes the reality for Puerto Rican children very early on, right. They become, they take on the responsibility of what it's going to mean to be Puerto Rican, under US occupation, children, and then teachers as well, right. And so they start bringing in, you know, educators from the United States, who are also going to help in training Puerto Rican teachers across the archipelago, to become part of this social process that's going to happen on the island, right? But the the problem is, is that they start using Americanization practices that are working in New York, Chicago, Detroit, to talk about European immigrants or engage with European immigrants who are going to have access to whiteness. They tried to impose that on these racialized bodies, who, you know, whose entire system is framed around Spanish language, right? But then also who education in some ways is on you, or this form of education is new, because education look really different under, you know, Spanish colonial rule. And so this idea that you can impose or use a system or these ideologies that are working for European immigrants in the United States, on Puerto Rican bodies is not going to work, right. And so we see then, that these migrants, what people don't think about, and this is, you know, the argument that I'm trying to make really early on in the book is that when these, you know, labor, migrants moved to Chicago in the 1940s, 1950s, you know, and their children started attending schools in Chicago, the parents of those children were educated under US ideals. They were the ones who are at the receiving end of the these Americanization, you know, practices there. They were the ones who are having English imposed on their schooling like really, really early on, right, who were being forced to learn to be American, as schoolchildren. And so there's a disconnect there, right. And it's not one that I explore fully in the book. And I'm hoping to return to it in some way. But it's very clear that if you don't have a conversation about what education looked like, across the archipelago, for the parents and the children that are moving into it, then what kind of real investment do you have in creating a system that's going to work for them in Chicago schools, right. And so they enter, you know, classrooms in Chicago, that are monolingual, right? English speaking, they're not prepared to, to work with with students who are either, you know, only speak Spanish, or some of them are, you know, bilingual too, because some of them were exposed to English, but then also that you don't have a clear understanding of who these people are, right? Who they are in terms of their cultural identity, their ethnic identity, what kind of migration history that these, this population had, because not all of them are coming from straight from Puerto Rico. Some of them are moving from New York and from other US cities to Chicago. And so there is no clear understanding of who the population is as children, right. And so if you have no investment in finding out who these children are, right But then how is it that you are expected to educate them? How is it that you expect them to engage them fully in an education and educational system that's not invested in them. And this is what they're walking into, right? Very early on, they're kind of spread across the city. And so they don't have the same kind of enclave that we see developing in the 1960s and 1970s. So very early on, they become very isolated in these individual schools in these community communities. And again, meeting on Americanization, these Americanization programs that aren't working for them, but this time people are starting to in the background are starting to have that conversation, right. And so we start seeing some social agencies and some some groups and some scholars, you know, coming out of the University of Chicago during that time period saying like, telling people, "Hold on. We have to, we have to have a very thoughtful and intentional conversation about how we're going to engage with the population. What does Americanization look like, for not just for Puerto Ricans for but for indigenous populations, and for Black Americans who are now coming, you know, moving to Chicago in high numbers as well, because these are citizens, right, and Americanization programs, the initial tool of them is to create a citizenry. But these people are already citizens, right. But we're not taking that into account. And so schools become a site in which these conversations are forced to happen. Because, you know, by the, by the 1970s, you have, you know, a drop out or push out rate for Puerto Rican students that has reached over 70%. And it's because of that history. And these are, you know, students who are not first generation for the most part at that point by the 1970s. Right. But they have experienced a system of education that has failed their community for a few decades at this point.

Kelly Therese Pollock 26:51

One thing I think we we have to talk about, at least briefly, is Richard J. Daly, who is sort of a massive precedence over all of this. He is the mayor of Chicago for the majority of the time period that you're writing about in this book. And of course, the the system of government in Chicago, then and in a lot of ways still now is very much a strong mayor system, the Board of Education is appointed, not elected. So can you talk a little bit about that, how that sort of frames the relationship with the community?

Dr. Mirelsie Velazquez 27:23

Daly, and or the Dalies at this point, because I graduated from high school under the second Daly, you know, so I inherited that system in a lot of different ways. But what Daly is doing very early on with the population is trying to sell them as acceptable neighbors, right, and is trying to sell Puerto Ricans as, or trying to try and create a narrative, using their citizenship really interesting me right, that he's using their their citizenship as a way to differentiate them from other, you know, populations, right? That if, you know, if we welcome them, then they're going to become our neighbors, right. And so, you know, he starts recording news reels, he really is pushing this narrative right, around Puerto Ricans, because he needs to push them or at least bring them into the city as laborers. There's a need for them during these, you know, these particular moments in history. And so but then Daly, while he's trying to force others to welcome them as neighbors, is not being intentional about what that's going to mean for them as a students in schools, right. And this is happening, you know, the 1960s and '70s in Chicago, are, are framed, or at least around educational history, are framed around community activism, especially around the Black community and what they're doing transform that then, you know, the rest of us get to inherit in a lot of different ways, right. And so, you know, Daly for, for for whatever it's worth was smart. He knew he knows what he's doing, right? He also knows these numbers, their numbers are growing in the city. So I need to support them, or at least, publicly engage with them in a particular way, because I need their votes. They're starting to create a voting bloc. And that's what we see in the 1960s. Right. And so when when we get to the point of the Division Street uprising of 1966, he's very quick to respond, actually. He's very quick to respond on the surface, about the kind of programs that he himself sees the community needs, right. And English language acquisition becomes a way that or at least comes becomes the main framework that he uses. Right. And so he enters the picture in terms of creating a working relationship with the community after the uprising, when the uprising shouldn't have happened to begin with, right. It happens under his his watch, right? We see an increase in police brutality, right Chicago police towards the community during that time period, and this is what happens with the 1966 uprising. And so he waits for this to happen in order to publicly respond. And the conversation becomes framed around increasing participation or relationship around police and community relations, increasing language, English language acquisition and programs within the Puerto Rican community, which at this point, the population is at its highesties numbers living in Humboldt Park in Chicago, bringing in representation on Chicago Board of Education, right. And the the first person that is appointed, the first Latina or Latino pointed out in Chicago Board of Education is Maria Sela, a Puerto Rican woman. And so he's very intentional about what he's doing, because he needs those votes. But he's very intentional in the way that he approaches a segment of the population that could be categorized as middle class. They're the business owners. They're the community leaders, or self proclaimed community leaders. They're the ones who founded newspapers in the community, right? So he's very intentional about how he's navigating that space, because at the end of the day, he knows that it's going to mean votes for him. It has nothing to do with the community itself, it just becomes part of the daily machine, the Democratic Party, in the city during that time period. And so the uprising awakens him to realizing they're a force. And so now I have to align myself in a particular way with the community, because the community is no longer gonna sit silently and wait for these things to happen to them. In some ways, it works for him for a decade. You know, you see representation across social agencies across the city, you see your representation on the board of education, you also see the creation of programs in the city. But again, a lot of these programs, what people aren't realizing it's not the city actually supporting them as they're using federal money to do it. It's not the city itself, that's doing it. But then on the other side, when he's called out for the things that aren't working for particular communities, especially around education, he retaliates, you know, towards the city, he's also appointing people on, you know, superintendents to lead Chicago schools, who then recreate harm. Right, and that we still see that happening in the city today, too.

Kelly Therese Pollock 32:09

Yeah. So let's talk some about the the effects of the 1966 uprising. So there's these sort of official effects and things that are put into place. But there's also this larger sort of community effect of realizing we, we have a voice I mean, of course, they knew that that's why it happened in the first place. But, you know, a really sort of, okay, we have this, this a certain amount of power, how can we use this? What can we do and sort of drives a lot of what happens in community activism after that point. So can you talk a little bit about that, and sort of the, the far reaching effects of this uprising?

Dr. Mirelsie Velazquez 32:47

One of the interesting things that also happens with the uprising is that it reminds the Puerto Rican community itself that they can't do this alone, right. And so what we start seeing is mobilization across groups, right. We see, you know, the Black community, the Puerto Rican community and the Mexican American community in Chicago, looking at ways that they can work together, right. And some of that comes with the creation of organizations. What folks have argued, what that then leads to is to, even though it hasn't been mapped out that way, it actually is what leads to the election of Harold Washington later on, right, that mobilization that happens in the 1960s. You know, where these groups are realizing we can't do this together, we have to be in conversation with one another, because they're almost creating these these invisible borders, between our communities, right, so that we don't engage with one another, right? And so in '66, you start seeing Puerto Ricans reaching out to other organizations and other populations in the city to engage in acts of transformation. With the community itself, Puerto Rican community itself starts creating agencies and organizations that are community based, right and so we see organizations that their sole focus is to ensure the sobrevivencia, right, the livelihood of the Puerto Rican community, right. And that might mean helping educate new migrants on social services available to them, right, using citizenship as a way to remind them nope, the city actually has a responsibility to you. They have to provide resources for you, you have legal recourse that you can engage with if landlords aren't meeting your needs within within these spaces, right, while they're also trying to battle urban renewal and gentrification that's pushing them into these neighborhoods. Right. And that's what we see or, you know, groups such as the Young Lords actually confronting during that time period, right. You know, here's youth led organization that has experienced the city first as students because they, you know, for the most part, most of them were students across city schools, whether parochial or public schools, who then transform this one street gang into one of the leading organization, community based organization that's going to help transform Puerto Rican community in the city in a lot of different ways. Right? And so we see different groups within a community itself, utilizing their cultural capital and their social capital in order to enact change. Right? You see that with the Young Lords, we see that with Claudio Flores when he founded "El Puertorriqueno" the newspaper in the city that then became a platform for then the community to stay informed about what's happening, and engaging with one another in that space. We see that with the creation of us, Vida incorporated Illinois, which becomes, it's part of a national organization that began as a way to increase access and resources for Puerto Rican students, starts out in New York and then gets brought to Chicago by a Puerto Rican woman lead that I made is in the 1960s. So we start seeing these, these individuals enacting change from their position, and at times, overlapping with one another. And so you know, when we look at history, as outsiders, as people who aren't experiencing it, we, we assume that they're siloed. But one of the things that I was able to find out later on, is that even though these organizations looked like they were in conflict with one another, that they were secretly supporting one another, right? I remember Cha Cha Jimenez telling me once that even though their newspaper, the Young Lords newspaper was seen as a radical, you know, space, right, and they themselves were a radical organization that, you know, middle class Puerto Ricans in the city weren't engaging with because of how they viewed their politics, that members of what then became, you know, the, the self proclaimed elite,Puerto Rican elite in the city, were actually funneling money to them without people realizing that they were doing this. And so it's interesting to see that even though they were creating their own spaces and their own organizations as a response to the 1966 uprising, because all of these groups are coming out after uprising. So even though they're coming out separately and utilizing their own positionalities, they're actually in conversation with one another in different ways. It's not always perfect, right? Because, you know, these are, this is a community that has been defined by how they view the relationship to Puerto Rico itself, right, whether you believe in self determination of Puerto Rico, whether you lean towards statehood, whether you lean towards Commonwealth status, right, that's how these organizations actually kind of function, that there's moments in history that they come together, because they realize that even though the ways in which they engage in community based organizing or action may be different at the end of the day, I do believe and I think they all believe that what they wanted was to better the community. They just couldn't agree on under whose terms I was going to happen.

Kelly Therese Pollock 37:41

I want to ask too, you talk a lot about the role of women and women's activism in this space in ways that's not always obvious, because they're not necessarily the ones whose names are on the masthead of the newspapers or have the positions. But can you talk a little bit about that, and how important it is that that these women are taking really important leadership roles, especially in the fights for education?

Dr. Mirelsie Velazquez 38:06

I start that with the 1940s, because in the 1940s, you have two, two different migrations happening even at small numbers to the city, right? You have labor migration happening and women become, Puerto Rican women become part of that, right? You have a group of domesticas, domestic workers who are coming to to work for middle class, or affluent families in Chicago, during that time period and becomes organized by a labor agency, an employment agency. But at the same time, you have a really small group of women who are coming as students at the University of Chicago, right. And so here you have domestic workers, and also University of Chicago, you know, students, graduate students, who then cross paths, and they cross paths, because they're both seeking, you know, spaces in which to socialize. Right. And they're looking for places in order to be Puerto Rican, you know, in a city that they don't recognize, that's not familiar to them. Right. So what ends up happening is that you, you, you see, the University of Chicago students, and particularly in Elena Padilla and Muna Munoz Lee, finding out what's happening to the domesticas within their employment, site of employment, right, that they're being exploited, that they're not being paid what was promised them, that they're actually been harmed in a lot of different ways. And so these women at the University of Chicago, these students then use their capital, right, and the relationship that they have with leaders either in New York or in Puerto Rico, in order to enact change for these domesticas, and that change also benefits men because the men that were coming too, as laborers were also being exploited, right. But it was women organizing, that actually enacted the type of change that then helped them to not be further marginalized, but also to humanize through these labor contracts. And so we see this genealogy of empowerment, developing really early on those earlier migrants in Chicago, and that this change being acted by women who are still doing it in, they're still doing it in a very gendered way. And I don't mean that in a negative way. But the the spaces that they're allowed to occupy within the city, whether as laborers, whether as mothers, whether as educators, and then in the 1960s, we see that further happening with, you know, women appointed to the Chicago Board of Education. We see that with, you know, women creating these, you know, community wide, and also national organizations within the city. But then we see that through women like Carmen Valentine who become really active as an educator herself, within the Chicago Puerto Rican community, right. And so we see these women become the ones who are both organizing, but then also putting themselves out on, you know, on the line, when they believe that there's injustices happening to the Puerto Rican community. And so they start utilizing their own social capital and their own positionality to enact change under their own terms. And they're, they're not given credit for that, right? We don't view them. We don't view them as the ones who are community leaders, because they're acting out within these gendered roles, the way that it's written, or at least people view them, although they're the ones who really are calling out these systems in a lot of different ways. Right, you know, Maria Sela was very vocal on the Chicago Board of Education, actually only serves one term, because she realized that she can do a lot more change, if she becomes part of creating these other larger organizations and utilizing that capital, right, and then becomes very active in city politics and in different ways, right and not as a politician, but informing the ways in which politicians are are engaging with both the Puerto Rican with the larger Latin X community in Chicago during that time period. Carmen Valentina is very vocal, but because of her engagement with the Puerto Rican and the Independence Party in Chicago, that's what how history remembers her. They only remember her as someone who then is imprisoned because of her role through the Puerto Rican independence movement, not as an educator, not as someone that forced the Chicago public schools to start recognizing their responsibility to Puerto Rican children. And, you know, and was very active in forcing the city to create a new high school for the Puerto Rican community, you know, moving from Tuley High School to then Roberto Clemente High School, and also forcing the city to recognize that you have to engage with with who this community is right, including them in curriculum, including the voices of parents and the community at large, in order to support students best. That's not how history wants to remember her. They want to remember her through how she's viewed as a very active participant through this other movement, right through her acts of resistance, and not viewing her as someone that was engaging in transformative acts within within school spaces, right within these systems and change the system in a lot of different ways. And so it's always interesting how women are remembered throughout history, right, you know, and it's never under their own terms. My initial hope was going to be that the entire book was just going to be about Puerto Rican women; but the problem is, is that the archives don't allow for that. And that some of those early leaders have either passed on or are not accessible in order to collect their oral histories, or even finding out their names is so hard to do, right? They become these nameless individuals in the footnotes of history, including in board meetings, including in newspaper accounts, even the cover of my book, right? I can't even give a name to the people who are on the cover of the book, because the journalists and photographers that were engaging with them didn't document them in that way. And so many of us have taken on the responsibility to kind of, again, going back to the idea of bringing out these individuals out of the footnotes of history, because in a lot of ways history wants us to remain in the footnotes.

Kelly Therese Pollock 44:11

Yeah. So I do want to ask, as we're recording, there is, of course, a devastating hurricane that has just hit Puerto Rico before it's even had a chance to rebuild from Hurricane Maria. So I wanted to ask just how listeners can help support the people both who are in Puerto Rico and the larger Puerto Rican community.

Dr. Mirelsie Velazquez 44:34

You know, I so I'm teaching my Latina feminism class this semester, and it just happens to be that we were talking about, you know, Puerto Rican women when it was happening. And my intent was to kind of talk about the consequences of the five year anniversary of Hurricane Maria, and what it meant for many of us who are living in the diaspora, to have to contend with the silence of not knowing how our families were. You know, it was about a week and a half before I knew how my, my, you know, some of my immediate family were before I can hear from them. And so instead of being able to prepare a lecture that was dealing with, you know, history, I was still up that that night, you know, trying to figure out what am I going to hear from my family? Again, here we go again, because there was no response to Maria. That's why category one hurricane, devastated, you know, the archipelago again, right? Because there was no response. And so I, you know, I asked someone, or I reminded someone who had sent me something about, you know, something scholarly about Puerto Rico, I responded with, "Have you asked your students how they are? Have you just asked people how they are? Because I know that you have students, right. I know that you have colleagues, you know, in these spaces, have you bothered asking how people are because we're not okay." And so, you know, very quickly on what I appreciated, was on the ground, and I know, there's folks on on, on Twitter that I follow, or, you know, Puerto Rican activists that I follow, were starting to mobilize reminding people do not send money and resources to these organizations, because what ended up happening after Maria is that these things that people were sending to help our island, the local government wasn't dispersing. And so there's ways to engage with the local community there. And there are organizations, you know, there are folks that you can follow to have these type of conversations with. There's organizations, the Puerto Rican Agenda, in Chicago is a wonderful resource and organization to kind of keep in touch with to kind of see how they're how they're mobilizing to support the community. You know, there's folks like, I want to make sure I get this individual's name, right. But he's very active on social media to make sure that sharing information, I believe his name is Alejandro Palilla. There's folks on social media that you can follow, that you can engage with in order to figure out who are the local organizations who are doing this work. Because what helped means to one group or one segment of the population may not be what it means to other. I would tell people to keep an eye out because one of the things, one of the devastating things that happened out of Maria, Hurricane Maria, was that there was an increase in gender based violence. Because if you are trapped in these spaces, some people are trapped with their abusers. Right, or they can't call for help, or they can't engage in these type of conversation. So start looking and start engaging with some of the local organization that are helping for keeping an eye out on gender based violence, but also keep an eye out on violence that is directed towards queer communities on across the archipelago as well. So there's so many different ways that people kind of engage just be mindful that some of the organizations are probably better at helping and dispersing aid. And right now, Twitter's probably the best way to kind of find out who who to help, how to help and how to engage. But also start out by asking how people are, because it's been a difficult couple of weeks for people, and it's going to continue well, it's been a difficult, what, 124 years? I think that's last time I did the math. And it continued to be to be that for for the larger community as well.

Kelly Therese Pollock 48:12

Yeah, yeah. And I would encourage people to keep paying attention, because of course, when the immediate crisis is over, it's not really over, as we see from not putting in the resources to recover after Maria.

Dr. Mirelsie Velazquez 48:24

Oh, but thank you, thank you for asking, because asking, you know, asking a simple question is the beginning of of figuring out how folks can help others as well.

Kelly Therese Pollock 48:34

Yeah. How can people get your book?

Dr. Mirelsie Velazquez 48:38

So the book is available at University of Illinois Press. I welcome people to support you know, presses, but then also support local bookstores. I know for folks who are in Chicago, there are copies of my book available at Women and Children First Bookstore, who have always been generous to support, you know, local, local authors across the city, especially women across the city as well. And so first choice, of course, the press, but then also support local, local bookstores, across the city and across the country as well, because if we don't support locally owned bookstores, then they're going to continue to disappear. So at this point, if people buy books, we're just we just have to support support, folks, because especially for academic books, we're not in here for the money. Many of us are writing community based histories, because we want to make sure that our histories are out there for people to enjoy, and to engage with.

Kelly Therese Pollock 49:29

Yeah, and I'll put a link in the show notes as well. Was there anything else that you wanted to make sure we talked about?

Dr. Mirelsie Velazquez 49:35

Keep supportingfolks who are engaging in these types of conversations, because it's both, you know, both makes me happy to share this work, but it also it's disheartening that it's 2022 and this is the first time that people are hearing about or learning about a community that's been there very early on and has been very instrumental in building the city in a lot of different ways, you know, as laborers, as educators, as activists, as people who are engaging in acts of transformation that are going to inspire hope, in others. And so read these histories, ask, you know, ask about these histories and support those who are engaging in this type of work, because I don't I got asked by someone, "Well, what are you going to move on to next?" assuming that I was not going to continue to work on Puerto Rican history. And I just looked at them like, "No, I'm just going to keep writing about this. Because if we don't write about our own community histories, then no one no one's going to be interested in doing the work." So ask questions and engage with it, especially with young people too who are doing, who are doing this work in very interesting ways.

Kelly Therese Pollock 50:36

Well, thank you so much for writing this book and for speaking with me today. I learned a ton and I agree that it it's unfortunate that I hadn't already known it, but I'm so glad I do now.

Dr. Mirelsie Velazquez 50:47

Thank you for having me.

Teddy 50:49

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. You can find the sources used for this episode @UnsungHistorypodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or our used with permission. You can find us on Twitter, or Instagram @Unsung__History, or on Facebook @UnsungHistorypodcast. To contact us with questions or episodes suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistorypodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate and review and tell your friends.

Mirelsie Velázquez

Dr. Velázquez is a historian of education interested in issues of race/ethnicity, historical research in education, and gender and sexuality at the University of Oklahoma. She teaches courses on History of American Education, Puerto Rican Studies, Critical Race Theory, Latina Feminism, Latina/o Education, Oral History, and Historiography of Education. Her forthcoming book, Puerto Rican Chicago: Schooling the City, 1940-1977 (University of Illinois Press), chronicles the Puerto Rican community’s response to the urban decay in which they were forced to live, work, and especially learn. Her work has most recently appeared in the journals Latino Studies, Centro, and Gender and Education. Velazquez has also completed several book chapters that examines the role of oral histories in highlighting and inserting the experiences of Latina/o communities into historical scholarship. Throughout her scholarship, Velazquez articulates the importance of including the work of Puerto Rican women and other Latinas in confronting the schooling inequalities experienced by the community’s children. Velázquez is currently completing a research project on the history of Black and Indigenous education in both the Oklahoma and Indian Territories, beginning in the mid-19th century until statehood in 1907. Locally, Dr. Velázquez is working on issues pertaining to community involvement in Latina/o and African American communities, as well as access to higher education for underrepresented communities of color.

Research Interests:

History of Education

Latina/o History

Social Movemen…

Read More