Chinese Grocery Stores in the Mississippi Delta

During Reconstruction, cotton planters in the Mississippi Delta recruited Chinese laborers to work on their plantations, to replace the emancipated slaves who had previously done the hard labor. However, the Chinese workers quickly learned that they couldn’t earn enough money picking cotton to send back to their families, and they turned instead to running small grocery stores, filling a niche in the market of the Deep South. At one point, the city of Greenville, Mississippi, had 40,000 residents and 50 Chinese-owned grocery stores. Although the numbers of Chinese Americans living in the Mississippi Delta region had dwindled now, their legacy remains.

Joining me to help us learn about this history is filmmaker and musician Larissa Lam, director of the 2021 documentary Far East Deep South, which follows her husband’s family as they search for their own lost family history in the Mississippi Delta.

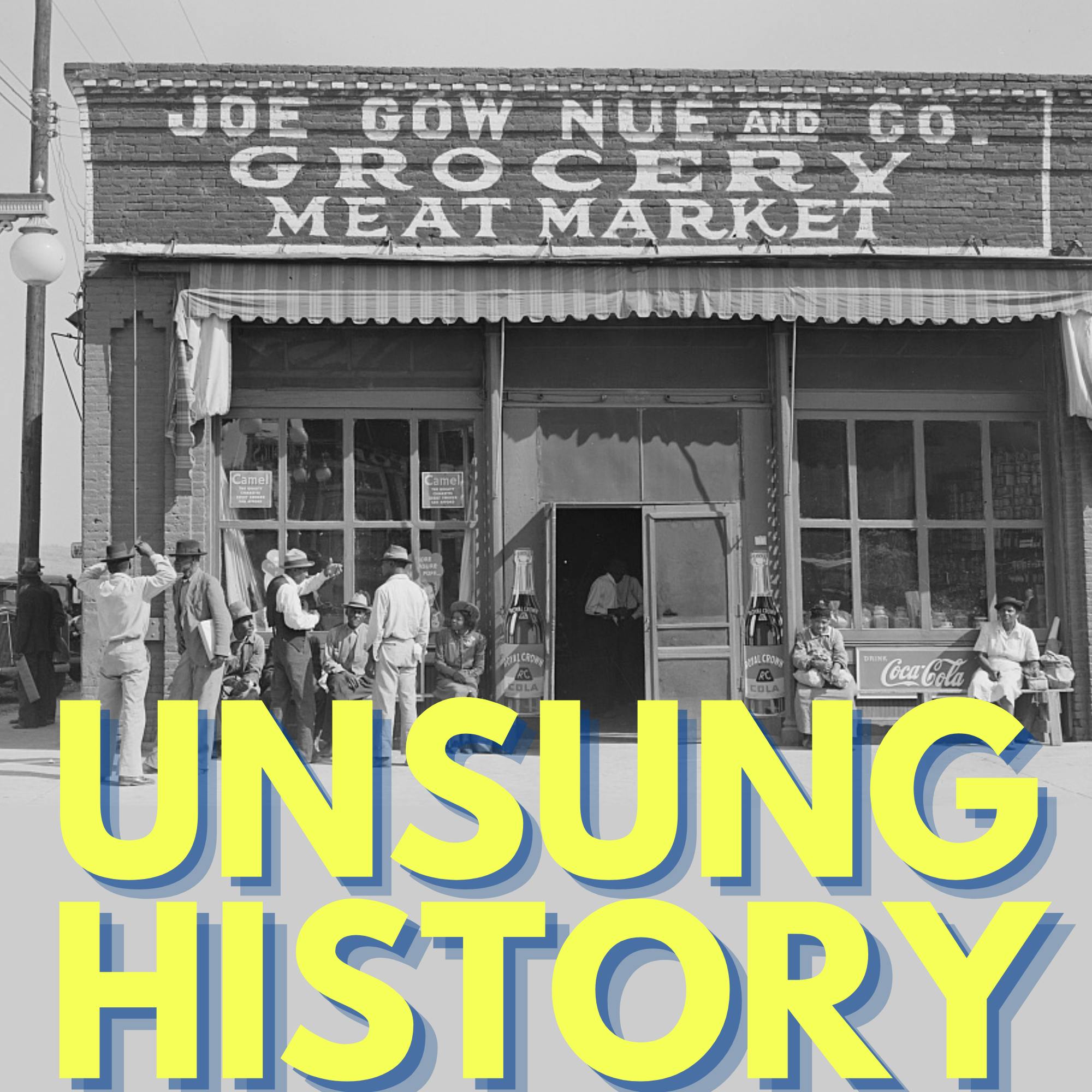

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. Image Credit: “In the Mississippi Delta. There is an ever-increasing number of Chinese grocerymen and merchants.” Marion Post Wolcott, photographer. Leland, Mississippi, 1939. The photograph is courtesy of the Library of Congress and is in the Public Domain. Audio Credit: “The First Day,” by Larissa Lam, from the 2015 album Love & Discovery, Label: LOG Records/Del Oro Music. Song clip used with permission of the artist.

Additional Sources:

- “The Legacy Of The Mississippi Delta Chinese,” Melissa Block and Elissa Nadworny, NPR, March 18, 2017.

- “Chinese in Mississippi: An Ethnic People in a Biracial Society,” Charles Reagan Wilson, Mississippi History Now, November 2022.

- “Neither Black Nor White in the Mississippi Delta: Two photographers document a community of Chinese-Americans in the birthplace of the blues,” James Estrin, The New York Times, March 13, 2018.

- “The Grocery Story of the Mississippi Delta Chinese,” Victoria Bouloubasis, Somewhere South, April 13, 2020.

- Mississippi Delta Chinese: Life in Chinese Grocery Stores.

- “Op-Ed: How African Americans and Chinese immigrants forged a community in the Delta generations ago,” by Larissa Lam, Los Angeles Times, April 4, 2021.

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Kelly Therese Pollock 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app, so you never miss an episode. And please tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen too.

Today, we're discussing Chinese immigrants and their descendants in the Mississippi Delta region. Chinese immigration to the United States started in small numbers in the early 19th century, with the first immigrants coming from China around 1815. These immigrants were usually men, drawn by the promise of economic opportunity. The first Chinese woman immigrant in the United States, was Afong Moy, who arrived in 1834. Early Chinese immigrants took part in the California Gold Rush in the mid 19th century, and Chinese laborers were recruited by the Central Pacific Railroad to build North America's first transcontinental railroad. As early as 1818, Chinese students were also coming to the US to study. The first Chinese graduate from an American college, Yale University, was Yung Wing, who graduated in 1854. By 1880, there were over 300,000 Chinese immigrants in the United States, many of them in California, where they made up about 10% of the California population. Despite being recruited to work in the US, these Chinese immigrants were often not welcomed, and as the anti-Chinese movement picked up, they faced legal barriers and outright violence. In one particularly brutal event, the Los Angeles Chinese Massacre of 1871, 500 people attacked the old Chinatown neighborhood in Los Angeles, killing 19 Chinese immigrants in one of the largest mass lynchings in American history. A number of laws, both federal and in California, restricted the opportunities for Chinese immigrants, including a foreign miners tax in 1850 that imposed a hefty tax on foreign gold miners. In 1875, the Page Act was passed, which barred immigrants who were considered undesirable. One category of these so called undesirable immigrants, was East Asian women coming to engage in prostitution. And the law was used in such a way so as to effectively prohibit the entry of all Chinese women into the United States. In 1882, this restriction was extended to Chinese men as well with the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act. This was the only law in US history created to prevent members of a specific ethnic or national group from immigrating to the United States. The Act prevented Chinese laborers from immigrating, specifying that, "Skilled and unskilled laborers and Chinese employed in mining" could not enter the country. Some Chinese immigration could continue, including diplomatic officials with proper certification. But even for potential immigrants who were not laborers, their status was often difficult to prove. For those Chinese already in the US, the act excluded them from US citizenship, rendering them permanent aliens. During Reconstruction after the Civil War, cotton planters in the Mississippi Delta region, recruited Chinese workers, mostly from the Guangdong Province of China to replace the emancipated slaves, who had been their previous unfree labor force. Chinese men arrived, planning to work on the plantations to send money back to their families in China. They didn't stick with cotton picking for long, since they found it wasn't a viable means to earning enough money to send back to their families.

Instead, as early as the 1880s, they opened small grocery stores in the Black communities in the Delta. There was nothing particularly Chinese about the grocery stores, other than the owners. But the stores filled a gap in the market, since they would invite Black customers through the front door and extend credit to Black customers, which white owned stores would not. At times, the Chinese community in the Delta served as a kind of middleman between the Black and white communities. In Greenville, Mississippi, a city of only 40,000, there were at one point as many as 50 Chinese owned grocery stores. The owners lived in the back of the stores, both to keep an eye on their wares, and also, because in many cases, they were prohibited from owning houses. Once they had families, their children would attend segregated Chinese schools in Greenville, and Cleveland, Mississippi, since the Chinese residents were subjected to many of the same Jim Crow laws that the Black residents were. It wasn't until after World War II that Chinese children were permitted to attend white schools. Once China was an ally of the United States against Japan, in World War II, the US Congress passed the Magnuson Act in 1943, which permitted Chinese residing in the United States to become naturalized citizens. But the national quota of Chinese immigrants per year was still only 105. It wasn't until the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 that the national origins formula was abolished, finally removing the discrimination against Asian immigration. By the 1970s, there were as many as 2500 Chinese Americans living in the region of the Mississippi Delta and across the Mississippi River in the Arkansas Delta, making that area one of the largest Chinese American communities in the American South. The population has dwindled since then, however, has many of the younger generation have moved to bigger cities with more opportunities. And there are now only about 500 Chinese Americans remaining in the area. To help us understand more about this history, I'm speaking now with filmmaker and musician Larissa Lam, director of the documentary "Far East Deep South," which follows her husband's family as they search for their own lost family history in the Mississippi Delta. First, though, please enjoy a clip of Larissa's music. This song is called "The First Day" and it's off her 2015 album "Love and Discovery." I'm using this clip with Larissa Lam's approval.

Larissa Lam 9:15

Steppin' out of the shadows, Feel the sunlight as the wind blows. A burden lifted off you shoulders Is a lesson learned as you get older. You thought this day would never come. Now the journey's just begun, just begun. Today is the first day of the rest of your life. Don't waste any time or throw it away. Today is the first day of the rest of your life. I hope you listen to what I say. Other days will be momentous, the possibilities are endless. What lies ahead will be even better than what you left behind forever...

Kelly Therese Pollock 10:48

Hi, Larissa. Thanks so much for joining me today.

Larissa Lam 10:50

Thanks for having me.

Kelly 10:52

Yeah, I'm, I've been excited to talk to you about this. It's such a unique story and something that I think people just don't know that much about. So I'm really excited to talk to you.

Larissa Lam 11:01

Yeah. And I'm really glad that your podcast spotlights all these little known pieces of history.

Kelly 11:07

Yeah. So let's start. Just tell me a little bit about how this documentary came to be. I know, this is your husband's family story. And I think this is the first documentary you had done. So So tell me a little bit about how the project came to be?

Larissa Lam 11:24

Well, I really kind of fell into it. And it really started when we took our family trip back in 2014. We live in California, and my husband didn't realize that his grandfather and great grandfather were buried in Mississippi, you know, until maybe his more later adult life. And so his brother said, "Let's take a family trip to go pay respects to the grave sites with their dad." And lo and behold, we end up in Mississippi. We weren't prepared to make a movie, we thought we were just going to put some flowers on a grave if we could even find the grave because at that point, we just had a photo to go off with. So my brother-in-law, Edwin, in his brilliance was just like, "You know, it's a small town in Mississippi. How hard is it going to be to find the cemetery? We'll just go to every cemetery and, and see if we can find it." You know, thankfully, he did call City Hall. So that was that was good. And they found that the cemetery was the New Cleveland cemetery. So we seriously thought that's all we were going to do. And next thing, you know, we walk into a Chinese Museum in the middle of Mississippi. And I had no idea that there was this rich history of Chinese living in the Mississippi Delta, until I stepped into that museum. And I was thinking to myself, like, "How come I didn't learn this in history? How come I didn't learn this? I took AP US History. I was a good student. I remember I would have remembered this in class. And how come we never heard about Asians being in the South, in a pre civil rights era?" And I was like, "This is something that more people need to know." And even the family revelations that we discovered, were so remarkable that I just felt like I needed to put this on on film, or I mean, part of it was on film, and I just needed to make it a bigger film.

Kelly Therese Pollock 13:04

Yeah. So what what is the process of making a documentary look like? And you know, as, as I was thinking, I interview lots of people. And I ended up airing nearly the whole interview when I put it out. I am sure that that is not what happens when you're making a documentary that you talk to somebody for an hour, and it ends up a little, you know, snippet. So what does that look like? What all do you do?

Larissa Lam 13:28

Yeah, the crazy thing is, we probably talked to each individual person that we interviewed, at least for an hour. And so our film was 76 minutes. So I couldn't put one interview in there, right. So it took a lot, a lot of combing through, you can imagine hours and hours of footage. But really for us, in doing this documentary, as well, we were on this journey of really going with my husband to trace his roots. And the first trip that we did, which I mentioned that we took in 2014, really, we discovered all this information in about a day and a half, or not even, one day and a morning with a family. And at that point, I made a short documentary called "Finding Cleveland," which was 14 minutes. And then from there, we expanded it to Far East Deep South, the 76 minutes. And there were still things to be discovered that we didn't even know we were going to discover, like going to the National Archives in San Francisco and a little spoiler alert, discovering the documents of my husband's great grandparents, great grandparents, and grandfather, which led us to even more revelations. And so I had no idea when I put this film together that it was going to encompass even the Chinese Exclusion Act, which is the files that we found at the National Archives. I thought I was making a film about his family, about being in the south. And then it turned into so much more. It was about American identity and history and even immigration history beyond just the story of the south. So all that to say is I had to kind of find the story. You know, if you write a script, or even write a novel, right, like, you know, the beginning, you know, the end, you kind of construct that. Documentary filmmaking is the complete opposite. You are filming, you are putting together pieces at the very end. And, you know, looking at what you have and going, how do I make a cohesive story that makes sense to people?

Kelly Therese Pollock 15:17

And you ended up splitting, I believe it's three sort of chapters within the story. How did you decide kind of the the framing of this story?

Larissa Lam 15:25

I think what was tricky about the film was that I wanted to kind of take the audience through the sequence of events almost as they happened, especially for that first trip that we took to Mississippi, which is in chapter one. And, and so in that I had to preserve certain things such as not bringing in anybody that wasn't part of that first trip. And I also wanted to put a spotlight on my my father-in-law, in a sense, because this was really his story. And I so the first chapter is the immigrants, the immigrant story. The second chapter is the southern story, where after that first trip, we went back to the south, and that's where we got to plunge more into the history and bringing all these other people that we meet. And then lastly, it became an American story. And, you know, I mentioned we went to the National Archives, that was kind of a surprise to us, because when I was making the film, I thought we would finish filming in Mississippi, that's the end of our story. Yay, there were Chinese in Mississippi. And then we ended up taking this incredible detour, in some sense, that made it a much larger story about how the Chinese Exclusion Act, and other immigration laws really separated my husband's family for generations, and the impacts that have been felt even to this day. And so, you know, if I, if I didn't section them off, it would almost feel a little bit like, wow, there's a lot going on. And so I think it helps, I think it helps the audience organize their thoughts. And it was, it was very much a last minute decision. It had been in the back of my mind, because that's how I kind of organized the story. But we decided to actually put that in there. So the audience would also know like, "Aha, yes, this is another section."

Kelly 17:02

So you mentioned your father-in-law. So talk to me a little bit about what it has meant to him and to his sons, to your husband and your brother-in-law, to learn about this family history.

Larissa Lam 17:15

I think it's been very life changing for them to know that they are not just an immigrant family, that they have deep roots in America. I think, you know, I know growing up, the American south when I learned about it in the history books, that to me was like, so quote, unquote, American, you know. It's like you think New England, and then you think the American South, especially as we study so much of history around those regions. And so as being a girl from California, which is obviously newer territories like I am, and being you know, Asian, I just never saw myself in history books, because we normally just learn about what the railroads Chinese building the railroads, then the Asian narrative kind of disappears from American history books until you get to Japanese internment during World War II. And it's not like the Chinese and the Japanese and others who came to this country kind of disappeared. It's like a lot of us have been in the country for a long time, just nobody gets to hear about it, because it's not been documented or told in our history books. And so I think for my husband and his family, there's like this new sense of pride and connection to I think American history that they never felt before. I think we always in our a lot of our, you know, Asian community and Asian American community have felt like perpetual foreigners because we're treated that way. But also, because we don't see ourselves connected to American history, we feel a little bit removed, but I feel like discovering this rich history down there has really connected their families, connected me, and my parents were actually born in China and I, to my knowledge, you know, I was the first one born in this country. But I feel a new sense of pride. I mean, I was always proud to be American, but I feel a stronger sense of belonging, if that makes sense.

Kelly Therese Pollock 18:56

Yeah. So that's sort of the sort of local the family reaction, but what do you think all of us watching this learning about the story can can learn about I think, both about race and Asian American history, but you know, America more generally, by by learning about this story,

Larissa Lam 19:18

You know, one of the things I always say is history is kind of like a photograph, right? You know, you're trying to capture moments and, you know, maybe you're flipping like, and, and for us, like, let's just say a textbook is almost like a photo album, right? You're flipping through photo albums. You you collected all these stories. And I feel like a lot of times there are people that have been left out of that story. And the simple analogy is like, think about looking through that photo album that your family has had a million times, but there's been some photos that have like quarters, like folded over for whatever reason, somebody put them in that way. And you just looked at that photo album a million times, and just never thought twice about it until one day you decide, "Let me peel back the pages and undo those corners," and you go, "Oh my gosh, I have other family members that were in that photo!" So I know there's a lot of discussion about race and ethnic studies, and you know, what do you put in? And to me, it's not like we're not trying to cram in extra history that wasn't there. It's just revealing what was there already, and you know, yet wouldn't was never told. And so a lot of times, I think like, "Well, we've unfolded that that family photo, we found a few extra cousins. I know, Thanksgiving might be a little bit more crowded, but let's invite them over for dinner, pull up a few extra chairs. There's plenty of food to go around. Let's share in this wonderful history together." And that's kind of how I really feel. It's like a story of ours is like, I don't want people to think like, "Oh, it's just a Chinese story. It's just an Asian American story." No, this is really an American story. And I feel like people should embrace, you know, all our beautiful colors together.

Kelly Therese Pollock 20:46

Yeah. So I think so often, when we think about the south, and especially the, you know, deep south Mississippi Delta, it feels like such a Black white story. And, you know, a lot of that history is, and that's a really important piece of it. So talk to me some about how these Chinese immigrants fit into that story. What what was, you know, what were their lives, like in the Mississippi Delta? How are they sort of navigating this terrain between the Black and white?

Larissa Lam 21:16

Yes, certainly, in talking to a lot of the Chinese that grew up there, they kept reiterating that they were really stuck in the middle, And to also broaden our picture of it not just being a binary, Black and white south; there were also Lebanese that were there; there were Mexicans that were there; there was a Jewish community. And so even that picture of Black white Chinese is not completely accurate. And so with the Chinese especially, they were initially brought in and recruited after the abolishment of slavery to work on plantations, because there was a need for labor. And a lot of the plantation owners heard like, because they did such a good job on the transcontinental railroad, that they were cheap, you know, and good labor to bring in. And so they were there were several hundred that were first recruited to go up to the Mississippi Delta. And then from there, I think different families and people I should say, different people around the country after they worked on the transcontinental railroad too, also started to migrate over to the Mississippi Delta. And there was this opportunity to make a long story short, to open grocery stores, and serve the Black community, in neighborhoods that white communities didn't want anything to do with. As most people know, this is during the Jim Crow era, where Black customers had to go through a separate entrance and were treated terribly, you know, in any type of establishment. And so the Chinese filled a void in a sense, where it allowed the white community and to not deal with the Black community, and at the same time, it provided almost a safe haven for the Black community, because the Black community could walk through the front door. They were treated with respect, when they walked into an Asian establishment. And for the Chinese community, they needed work. And this was the only thing that they could do, because by, you know, at some point, after the Chinese Exclusion Act was enacted in 1882, labor was banned from entering, Chinese labor. So they couldn't become they couldn't work on farms. They couldn't do those other jobs, they had to be only merchants. And this was kind of a loophole to allow Chinese to stay in the country and even enter the country.

Kelly Therese Pollock 23:28

And so the Chinese Exclusion Act then also affected the ability of families to be together, and that directly affects your your husband's family. Can you talk a little bit about that, that piece of it? And you know, why, why it matters that some Chinese people are allowed and even encouraged and recruited to come over? And some are not.

Larissa Lam 23:50

Yeah, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was something I personally didn't grow up learning about. It was only you know, within the last 10-15 years, I really had some, you know, knowledge of it basic, basic knowledge of it. And until I went through this whole research journey with my husband, that I realized how deep this law reverberated across, you know, decades, and especially when it comes to immigration policy. So I'm gonna back it up from the 1882 Exclusion Act to the 1875 Page Act, which actually prohibited Asian women from coming into the country. So already, you know, again, going back further in history in our little time machine here, during the, you know, mid 1800s, when you had the miners and then of course, the transcontinental Chinese workers come in. At some point, they started to become a little bit of a threat to current labor, especially with the previous wave of immigrants, which was predominantly Irish, there was starting to be some jealousy and refrains of, "They're taking our jobs. They're corrupting, you know, our society." I mean, I'm actually being nice because if you actually read the historical documents there was some pretty heinous language that was used to describe the Chinese community at the time. And so there was a lot of laws that started to be enacted to kind of prevent more Chinese to come over. Of course, if you limit women from being able to come, you can't have children, you can't procreate, because also, laws were in place for no interracial marriage, you know, there was anti-miscegenation laws. And so this created a bachelor society where a lot of Chinese men like my husband's grandfather and great grandfather ended up having to go to China to find a wife, and maybe have a family there. And then they came back to work. So it was a very, very long distance commute, you know, the way Dr. Gordon Chang in our film describes, which happened a lot with different families.

Kelly Therese Pollock 25:47

Yeah, and it's, it's heartbreaking to hear your father-in-law in the film talk about growing up without a father, because that's essentially what that meant, then is that his dad was somewhere else where he could work and make money, but he couldn't bring the family over.

Larissa Lam 26:03

Yeah. And, and it was hard, because my father-in-law had no idea that there were laws in place. You know, he's just a kid. You don't know why Daddy left, right. You don't know why Daddy can't come home. And he harbored so much bitterness and resentment, I think towards his father, until we took our trip to Mississippi and discovered that his father really did in fact, love him and miss him. And it was circumstances beyond his control for you know, not being able to reunite with his family.

Kelly 26:33

Yeah. So you, you have a podcast too. And in your podcast, in the most recent episode, you were speaking about, I believe you called it the joy and pain of AAPI history. So I wonder if you could talk a little bit about what what that means and what that means, as a person of Asian descent, to be thinking about AAPI history and having that sort of dual joy and pain.

Larissa Lam 26:58

Yeah, I think it's something that I didn't necessarily think about too much until recently, I was talking to some friends who were Vietnamese American. And their stories always couched around the Vietnam War, right. And that was a horrible war. It was also from an American perspective, kind of an embarrassment for our country, you know, a war that people regret getting involved in, you know, we didn't win. You know, we lost a lot of lives, spent a lot of time and money and energy, and it was like, why? You know. And yet for the refugees and the, you know, the descendants of refugees, they have a kind of almost a different perspective, where they've kind of put some of that past behind them. They're grateful for the opportunities, you know. They don't forget why they were here, but at the same time, they've created new lives, and they've created, you know, good memories in a sense, and that they didn't always want to be remembered as victims or like, "Oh, here are the poor Vietnamese, like, you know, you should be they should be so grateful to be in this country or, you know, being treated in that manner." And so I think, you know, those are some of the things we impact during our "Love Discovery and Dim Sum" podcast. And also, as we're talking here, I mean, I kind of joke that Far East Deep South is a really heartwarming film about discrimination. You know, because there's this wonderful story about my father, reconnecting, you know, with people that knew his family and discovering all these wonderful things. And there was so much hope, and there's so much joy in our film. But yet, there's also so much pain, right? We're talking about the Chinese Exclusion Act, which, you know, prevented Chinese for coming into the country unless they were merchants or scholars between 1882 and 1943. We're talking about Jim Crow laws and segregation and discrimination and racism, and like, you know, those are very, very painful memories. And so, you know, hopefully, what we showed in Far East Deep South, and certainly in our discussion in our on our podcast is that, you really need to have both because on one hand, I think our community has tended to maybe skew a little bit to more much to like, celebrating the the accomplishments and the achievements. And thereby you, you ended up creating the model minority myth, which I should say, the white community helped create, but we kind of perpetuated it, if we only focus on those things. And when we don't learn about the pain of the past, one, we can't learn from it. But two, people think like, "Oh, you're okay. The Asian community, like there's nothing wrong with them. Nothing bad has ever happened to them. You don't need to help them in any way. They, you know, they're totally fine." And yet across the board, that is actually not true, because there's actually a lot of disparity in income within the Asian American community on that people don't realize like not everybody's a crazy rich Asian. This is like why history is important and even knowledge beyond just one movie. It doesn't represent everybody, even though I liked Crazy Rich Asians. But yeah, my family doesn't look like that. Most families don't look like that. And so I think that's why it's important to balance that pain and that joy so that you see the spectrum of different experience with the Asian American community because there are those of us who are newer immigrant families, and then there are families like Baldwin's or even others, like Japanese American families that have been here four or five generations. And our editor on our film was German American. And you know, he's white, he's he can only go back three generations, his grandparents came to this country. And yet we look at him. And the bias is like, "Oh, of course, he's American." But if you look at a person of Asian descent, your your bias, your implicit bias is like, "Oh, they must not be from here, or their parents must not be from here." And yet, you know, Baldwin's family, in some ways, is even, quote, unquote, more American than our editor, Dwight's family who has only been here three generations. So those are the types of things we hope that we can convey with our film, and even just with our discussions on our podcast is reframing people's perceptions of certain communities.

Kelly 30:47

So you have a daughter who appears in the film, and has been in some other videos that you and your husband have made. Can you talk about how you talk about this piece of it, the sort of joy and pain and the AAPI identity, the Chinese American identity with your daughter, and how we can sort of raise the next generation?

Larissa Lam 31:09

Well, I have an eight year old daughter now, you know, she was, like you mentioned, she was much smaller when we were making our movie. And it's kind of neat to see her kind of grow through the process of the film, I'll just tell you a little bit about how I experienced growing up and why I don't want my daughter to go through the same thing. When I was in elementary school around her age, I grew up in a predominantly white neighborhood. And I was one of maybe, like four Asians in to like, 60 kids. You know, I think there were four Asians in my class. And I got a lot of the stereotypical questions of like, "Oh, do you know kung fu? And can you speak some Chinese?" and you know, a lot of those little things. And even from an identity point, I wanted to be Caucasian, I wanted to be white because all the popular kids were white. What I saw on TV and movies at the time, all the you know, the the models and all the superstars, they were Caucasian. They didn't look like me. And and so I had this, you know, unfortunate inferiority complex about myself. If anything, I was embarrassed to be Chinese. I had a Chinese middle name and like, "Why can't I have a middle name like Ann or Jennifer or Christine? Like, why do I have Lok-Yi? Oh my gosh, I'm never telling anybody my Chinese name. It's so embarrassing." And so there was this just sense of, like, shame that I had. And even as I kind of grew older, and even as an adult, and I was pursuing a career in entertainment, it was so strange that people kind of like I was before I became a filmmaker. I mean, I'm, I'm still still a singer, and a songwriter. And people would say, "Oh, well, you should go to Asia to be a, you know, a pop star." And this is even before Kpop, which don't even get me off off on that, because I'm Chinese American. And people think, "Oh, you do Kpop?" And I'm like, "No, I don't do Kpop. Like, you know, I'm Chinese. Kpop is Korean." And, you know, I was like, what, but I'm American. I was born here, I write in English, I don't read or write in Chinese. I'm illiterate. And so I was like, why would I be expected to do something in Asia because like, I'm American, you know. And so this this push and pull between people thinking I'm not American enough. And then if I go over to Asia, I'm actually not Asian enough. Because I'm not as fluent in the language. I speak conversationally, but I don't read or write. And so I'm not good enough to be American here. And I'm not good enough to be Asian over there. So where do I fit? And so for our daughter, what I really want her to learn, and what I want people to learn, you know, who watch our film in general is, you can be proud of your heritage and fully embrace that, you know, it took me a long time to finally be proud of my heritage and not reject it. And you can also be fully American in citizenship. You know, those two are not contradictory. So many times, I think people are asked to choose, and I think about my friends that are Italian American or Irish American. And you know, they were coming from immigrant groups historically. And they've gotten to the point now where I have friends that are very proud to be Italian, but nobody questions their loyalty to America, right? And they're, and they're still proud to be American, fully American, and they're accepted as such. And so I think that's the point I want my daughter to be at where people don't question, her Americanness, but they also can respect and she can be proud of her Chinese heritage.

Kelly Therese Pollock 34:22

Yeah, yeah. I love that. And, you know, as you were talking about your German American crew member, you know, my my grandma came over from England. It wasn't that long ago. It's totally true. And yes, nobody has ever questioned me about where are you from or anything like that. So about a year ago, Far East Deep South premiered on PBS, which was super exciting. And it is still, if people have PBS Passport, which I have, you can still get it on PBS that way. What are some of the other ways that people can see the film?

Larissa Lam 34:57

We're also on Kanopy, Kanopy with a K, which is part of the university system and many public libraries. So this is kind of a cool trick that if your library happens to have Kanopy, you can just sign up for use your library card to get a free account for Kanopy. And here's another hint, if you your library doesn't have Kanopy, find another local library that has Kanopy. And you can also sign up for a library card there to be able to watch our film. We also have different screenings with different organizations that are hosting them. And you can go to our website FarEastDeepSouth.com. to follow as to when those next screenings are and you know, we're constantly working on different deals. And education has been one of the primary focus, which is why it's on Kanopy and PBS. But certainly, we have some other interest and other parties that want to want to bring Far East Deep South to a wider audience.

Kelly Therese Pollock 35:50

And if people want to do their own screenings that they have a you know, like a community event or something is that something that can arrange as well?

Larissa Lam 35:57

Absolutely, my husband and I do a lot of speaking and screenings. And we'd love to do them in person if you know, one budget allows and COVID conditions allow, it's wonderful to do especially we've worked with a lot of, you know, company ERGs, a lot of their affinity groups, it's been a wonderful platform for people to talk about diversity inclusion issues. We've worked with a lot of universities and campuses and schools, as well as you know, different community organizations so they can reach out to us at FarEastDeepSouth.com. There's a booking form there. There's also a contact page. And I'll just mention one more thing for those who are teachers out there, and you're interested. I know a lot of times budgets are tight with public schools, especially in light of what's happened during the pandemic. And so for many underfunded schools, we actually started something called the First Class Initiative that teachers can public school teachers, K through 12, can actually apply to get a grant to show our film in their classrooms for free. And we also have a discussion guide that we provide for free that they can use to pull questions and activities for the students. So that is also on our website at FarEastDeepSouth.com. And, you know, definitely reach out to us if you have any questions about anything. We'd love to come show our film, we'd love to come speak wherever we can.

Kelly Therese Pollock 37:11

Yeah, I was remarking in another episode before that, you know, I feel like that is the thing that still isn't getting into schools, you know, is is Asian American Pacific Islander history that, you know, certainly my my kids are starting to get more and more Black history, definitely in school. You know, they're they're still, you know, it, I think it's starting starting to get some some more AAPI history in the schools. But, you know, there's a lot of room.

Larissa Lam 37:38

Right, well, Illinois passed the TEACH Act, which will now require, you know, Asian American history to be taught in schools. And I mean, I think the beauty of our film, too, is the fact that it's not just the Chinese story. You know, as I mentioned before, it does intersect with the Black, you know, experience of the South too. And, you know, you also meet some white community members. And I think that's the thing that as we're learning about and teaching history, it's like, we're not isolated from one another, you know, you can't teach one aspect of history without other aspects of history, because everybody's lives intermingle. And so now, you know, hopefully, people will see, it's like, the Black experience, you know, also, you know, influenced and impacted other communities. I mean, whether it's the discriminatory laws that started as the targeting the Black community, but was then applied to the Chinese community in segregated schools in the south, or even California, there was segregated schools for Asians, you know, or the Native American community or even the Mexican community and other parts, like these laws that started maybe targeting in one, you know, one group ended up being used and applied for others. And of course, on the the, the joyful side, the civil rights movement, you know, which, you know, Martin Luther King, Jr. and others paved the way. I mean, it didn't just benefit the Black community, it benefited, you know, all people of color.

Kelly Therese Pollock 38:56

Yeah. So, in addition to being able to find your film, where can people find your other work, including your podcast, and your singing?

Larissa Lam 39:05

Our podcast is Love, Discovery and Dim Sum. And so if you're listening to this podcast, you just have to google Love, Discovery and Dim Sum and you'll be able to add our podcast on there. And our music videos, you can well I go by my my real name Larissa Lam on YouTube. My YouTube channel's, I think youtube.com/LarissaLamMusic, and then my husband goes by a stage name, Rapper Only Won and so it's "Only W-o-n." Especially if you're wanting to look for our music videos like "Asian Americans Make History," which is our take on Hamilton in three minutes of Asian American history with a cameo by my daughter. Those are fun videos to kind of look up. And of course, we actually have a whole like menu of videos that are on our FarEastDeepSouth.com page.

Kelly Therese Pollock 39:54

Excellent. I'll put links in the show notes as well. Is there anything else you wanted to make sure we talked about?

Larissa Lam 40:00

Well, I really appreciate everything you're doing on this show, to really share all these diverse stories. And I think the last thing I just want to let our audience know is that your stories matter. You know, even though my husband's story is just a family story, all our family stories collectively make up American history. And a lot of times I think the focus is sometimes is on just like government or wars, right, like all those major things, but on a local level, you know, we always encourage people to get involved, like your artifacts in your home, maybe is living history, especially if you're from an underrepresented, you know, community. We actually partnered with the the neighbor settlement in Naperville, Illinois, one year where there was a, you know, huge Asian American population there. And they were wanting to get people's, you know, photos and stories and like old rice cookers, because they wanted to document for future generations, like this was the population that was here. And so, you know, there every city, no matter how small, has either a museum or a college or school or library that is kind of the keeper of these things. So if you don't see your story and your history represented, be proactive about it, you go talk to them and say like, Hey, especially if you're of Asian descent, you go like, "Hey, how come there's no, there's nothing here?" I'm only saying of Asian descent, because I'm of Asian descent, but like anybody, anybody wasn't meant to say we're better. Let's just go ahead. Just go ahead and talk to somebody out there and say, like, "Hey, you know, we should have more stories, more books, more artifacts from this particular community." And if you're not Asian, and you want to advocate for other communities like ours, please also speak up because we definitely need allies to go in and influence these various sectors of our community.

Kelly Therese Pollock 41:48

Excellent. Well, Larissa, thank you so much for speaking with me, and for this terrific film, I really enjoyed it. My husband and I learned a ton and now we're going to show it to the kids as well. So I really appreciate it.

Larissa Lam 42:00

Yeah, thank you so much. And, you know, I hope to see our film in more and more schools and definitely, you know, once again, if anyone's listening and you'd like to bring our film into school, please reach out to us at FarEastDeepSouth.com. We'd love to see our film, you know, be incorporated into the curriculum and the lessons at school. Thank you so much, Kelly.

Kelly Therese Pollock 42:19

Yeah, thank you.

Teddy 42:21

Thanks for listening to Unsung History, you can find the sources used for this episode @UnsungHistorypodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain, or our used with permission. You can find us on Twitter, or Instagram @Unsung__History, or on Facebook @UnsungHistorypodcast. To contact us with questions or episodes suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistorypodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate and review and tell your friends.

Larissa Lam

Over the past two decades, Larissa Lam has established herself as not only a creative force in music, film and TV but a voice that inspires and empowers others. A dynamic speaker and performer, Larissa has captivated audiences across the U.S. at Lincoln Center, The Grammy Museum, TEDx and more. She has won numerous awards for her music and films and has been featured on NBC News, CBS, NPR, LA Times among other media outlets. She is passionate about promoting better cross-cultural understanding and the importance of diversity and inclusion. This petite, Chinese-American woman is a true multi-hyphenate who defies stereotypes and expectations.

An accomplished songwriter and singer, Larissa has released four critically acclaimed solo albums of original songs showcasing her powerful, soulful voice. Her song “I Feel Alive” won the Hollywood Music in Media and Akademia Music Awards for Best Dance Song. Her song “Breathing More” was a Top 10 CCM/Rhythmic chart hit and was also featured in the video game, Dance Dance Revolution: Universe 2. She previously composed music for The Oprah Winfrey Show among other film and TV projects. She has collaborated with hit-making producers and musicians such as David Longoria (Sting, George Michael, Andre Crouch), Robert Eibach (Selena Gomez, Ariana Grande), Tim Schoenhals (Meghan Trainor, Katy Perry) and Derek Nakamoto (Janet Jackson, Keiko Matsui).

More recently, Larissa has gained recognition as a filmmaker with her award-winning documentaries, Finding Cleveland and Far East Deep South, which explore the little known histor… Read More