The Jackson State Shootings in May 1970

Just after midnight on May 15, 1970, officers opened fire on a group of unarmed students milling in front of a dorm on the campus of Jackson State College in Jackson, Mississippi, killing two and wounding twelve. Although the shootings took place just a week and a half after the shootings at Kent State University, the Jackson State shootings never got the attention of those at Kent State, and when they did they were often described as a second Kent State, erasing the context of white supremacy and state-based violence that inform what happened in Jackson.

Kelly tells the tragic story of the Jackson State shootings and interviews Nancy Bristow, Professor of History at the University of Puget Sound, and author of Steeped in the Blood of Racism: Black Power, Law and Order, and the 1970 Shootings at Jackson State College to find out more.

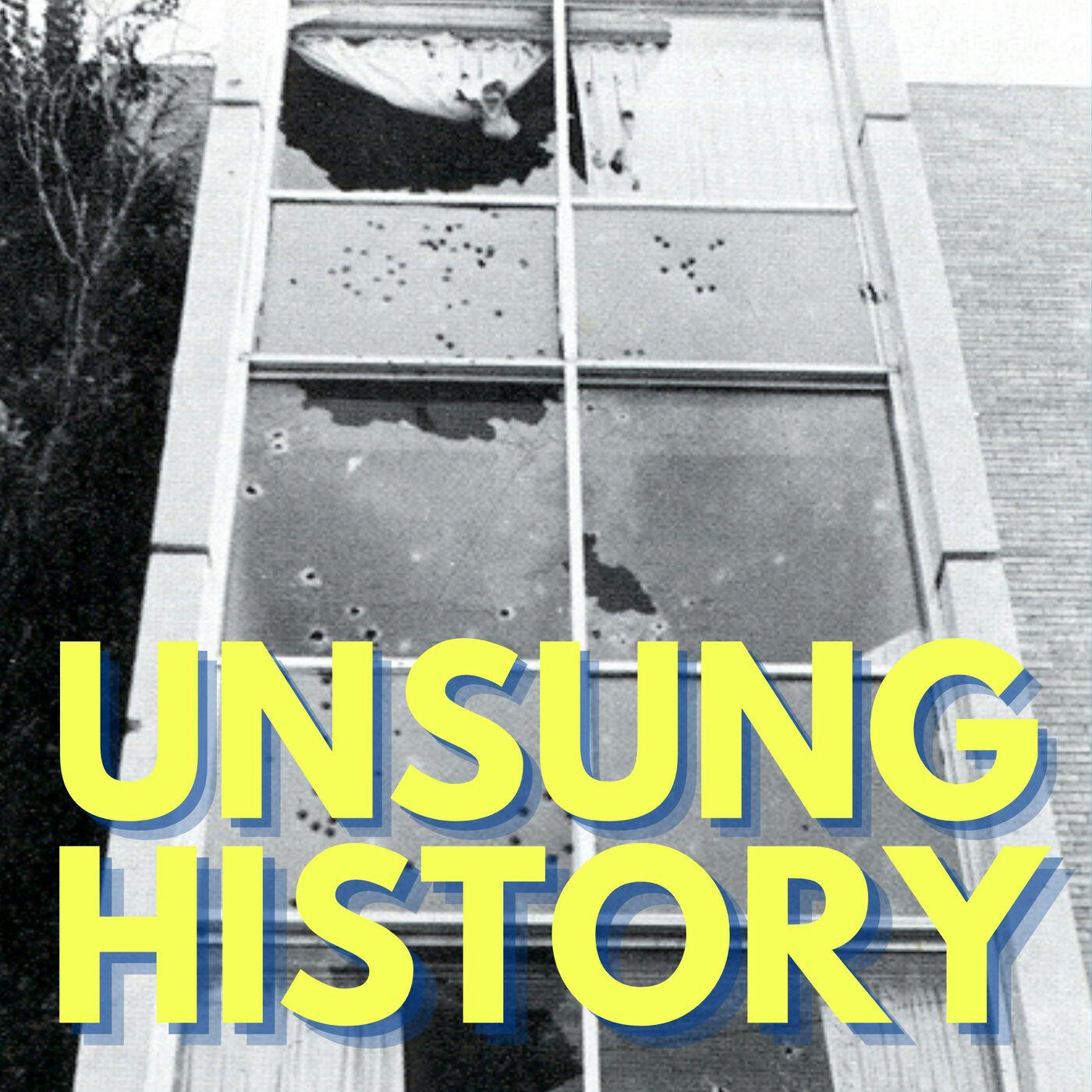

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. Episode image: Alexander Hall, viewed from across Lynch Street, National Archives. Public Domain.

Transcript available at: https://www.unsunghistorypodcast.com/transcripts/transcript-episode-2

Sources:

- Steeped in the Blood of Racism: Black Power, Law and Order, and the 1970 Shootings at Jackson State College by Nancy K. Bristow

- "The Report of the President's Commission on Campus Unrest." Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402, 1970.

- “Program about the Jackson State Killings, Jackson, Mississippi,” WYSO, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC.

- "50 Years After the Jackson State Killings, America's Crisis of Racial Injustice Continues—and Shows the Danger of Forgetting," Time Magazine, by Nancy K. Bristow, May 14, 2020

- "The Jackson State shootings are often overlooked. But Rich Caster still remembers." The Washington Post, by Kevin B. Blackstone, May 14, 2020.

- "GIBBS/GREEN 51st COMMEMORATION 2021," Jackson State University, May 15, 2021. [Facebook Video]

Support the show (https://www.buymeacoffee.com/UnsungHistory)

Kelly 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we tell the stories of people and events in American history haven't gotten much notice. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then interview someone who knows a lot more than I do.

Today's story is about the May 1970 shootings at Jackson State College. A note to anyone listening with small children. This episode may be upsetting. Jackson State College, which became Jackson State University in 1974, is a public HBCU (historically black university) in Jackson, Mississippi. It was established 143 years ago on October 23 1877, and is now one of the largest HBCUs in the United States. By spring of 1970, there were about 4300 students enrolled nearly all of them African American, and nearly all from Mississippi. As many people know, on May 4 1970, members of the Ohio National Guard fired at student demonstrators at Kent State University, killing for and wounding nine. Campus activism around the country was rampant before and after the Kent State shootings in response to the ongoing conflict in Vietnam and the draft, but there were only a few Vietnam rallies at Jackson State. In the wake of the Kent State shootings, a few hundred students at Jackson State did boycott class and attended a protest, but the students there were largely focused on finishing their upcoming exams. In 1970, the campus of Jackson State sat on two sides of Lynch Street, which was a major thoroughfare named after the black Reconstruction Era U.S. Representative John Arlidge. White motorists often drove through the Jackson State campus, and it had become a frequent site for confrontations. On the evening of May 13 1970, a group of girls alerted Jackson State President John Peoples that there were boys throwing rocks at passing cars on Lynch Street. Peoples asked Jackson police to reroute traffic, which stopped the rock throwing. But a rumor started that students were going to set fire to the ROTC building, as had been done on other campuses including Kent State. Although the attempt to start a fire was quickly quelled, the disturbance brought law enforcement to campus. That night, law enforcement allowed the crowd to disperse on its own. By 2:30am campus was quiet, but the stage was set for trouble the following night. On the next evening, Thursday, May 14, a group of students was again throwing rocks at passing motorists. There are various stories as to what caused the unrest that night. Some claiming it was anti war protesters, others saying that a passing motorist had shouted falsely that Charles Evers, Mayor of a nearby town and brother of assassinated civil rights activist Medgar Evers had been murdered. Whatever the cause President People's again as the police to barricade Lynch Street, which they did.

A group of students then commandeered a dump truck from a nearby construction site and drove it up Lynch Street, setting it on fire after it sputtered and died. That quickly brought firefighters, city police and Mississippi highway and safety patrol officers to campus. The arrival of law enforcement riled up the students. And somewhere between 150 and 400 students gathered in front of Stuart Hall and were shouting and throwing debris. At this point, the National Guard was called on to campus. Unfortunately, that call was made too late. Before the National Guard could take charge, Jackson police started marching toward Alexander Hall, a woman's dorm, although law enforcement later claimed that as many as 400 students were gathered there. Other eyewitness accounts put the number closer to 30 to 50. Women students were required to be inside by 11:30pm on Thursday nights. So at least some of the students there were men who had just dropped off their girlfriends or women who hadn't yet gone inside the dorm. There doesn't appear to have been a riot or disturbance happening before the law enforcement arrived. But their arrival did prompt students to start yelling insults. The students felt they were in the right and did not return to their dorms, but they did retreat. When a glass bottle hit the pavement just after midnight, the officers opened fire shooting for 28 seconds until a call of ceasefire stopped them. By then more than 460 shots had been fired. Two people were killed: Philip Lafayette Gibbs, a married 21 year old junior, with a toddler son and a baby on the way. And James Earl Green, a 17 year old high school senior and trackstar at nearby Jim Hill High School, who was passing through Jackson State campus on his way home from his after school job at a grocery store. 12 more students were injured. To this day, bullet holes can be seen in the facade of Alexander Hall, where bullets shattered dorm windows. Officers later claimed that they had seen a sniper in the window of Alexander Hall. But no evidence was ever found. President Richard Nixon established the President's Commission on campus unrest to investigate both the Jackson State and Kent State events. No arrests were made in connection with the deaths at Jackson State. The Commission concluded "that the 28 second fusilade from police officers was an unreasonable, unjustified overreaction. A broad barrage of gunfire in response to reported and unconfirmed sniper fire is never warranted." The area of Lynch Street on campus was permanently close to traffic and renamed Gibbs Green Plaza. To help us understand more about the context of this horrific event, I'm joined now by Nancy Bristow, professor of history at the University of Puget Sound, and author of the 2020 book, Steeped in the Blood of Racism, Black Power, Law and Order, and the 1970s Shootings at Jackson State College.

Hi, Nancy.

Nancy Bristow 6:40

Hello. Good to be here.

Kelly 6:42

Yeah. Thanks so much for joining me. So before we jump into this, I'll just mention that your book before this was about the 1918 Flu. So you seem to be sort of tapped into the moments that are about to happen in history.

Nancy Bristow 6:58

I'll be honest, my editor has been joking that my next book should be about puppies and kittens so that we can have that be what comes next as opposed to the social cataclysms I seem to anticipate.

Kelly 7:08

Yeah, yeah. So I could have had you on to talk about that. But I think a lot of people have, in the past year, finally caught up to talking about the 1918 Flu. But this story of Jackson State College still, so it's sort of hidden in history, and I think is so important. Maybe just to start out, could you tell me a little bit about how you got interested in this event, in writing about this?

Nancy Bristow 7:37

Well, I've been teaching African American history for about 30 years. And if you teach that history, it is inevitable that you discover that the through line, or one of the through lines in that story is state violence. The use of the violence controlled by the government against people of color, in particular Black people, to control and constrain them is just an ongoing theme. So, it had been something I'd been preoccupied by, interested by. And then I teach the period of civil rights. And in that era, there is the need by the state. And here I'm thinking, especially in the South, but I really want to say for the nation as a whole, to rethink how that gets justified. In other words, prior to the civil rights period, you really can murder Black citizens, and do so if you are an officer of the state without explanation. In the wake of the civil rights movement, there really is the need for a new explanation for this ongoing violence. And we get, then, what I call the "law and order narrative," and something that should be very familiar to people today, because we continue to hear that language used to justify this ongoing crisis that we see. And then third, I was really interested in Jackson State, because it's a story that's unknown. And it's so interesting, because it happens right along Kent State, which is well known. And I knew that my students knew one story and not the other. And so finally, I will give credit as well to an undergraduate at my college who wrote a paper about the students of Jackson State. And once he had that, in my mind, it wouldn't go away. So, also because John Moore put it in my head.

Kelly 9:08

Yeah, so I grew up with the story of Kent State. My parents were at Kent State during the shootings. And so I had always heard a lot about that story. And it wasn't until a year ago, I was interviewing my parents on the 50th anniversary of Kent State shootings. My mom mentioned the Jackson State shootings, and I had never heard of it in my entire life. So it's just this, it's sort of mind boggling that these things happen close to each other. And one is so well known and one is so little known. I want to tease out a little bit this. You just mentioned this context of the the civil rights era and the justifications for state violence. Can you talk a little bit about what that looked like in Jackson, Mississippi in those sort of years leading up to the shootings?

Nancy Bristow 9:55

Yeah, and I think that's such an important context. I appreciate that question. Because Mississippi, of course, has a long history reaching back to slavery of state brutality. This was state sanctioned use of force against African Americans who were seen to step out of what we'll put in quotation marks, but what would have been described as their "place." And what that "place" looks like shifts across time. When we get to the 1960s, of course, we had the civil rights period, and Mississippi is a hotbed for the white backlash, right? Think of Freedom Summer when the movement realizes the only way they can potentially break the back of segregation in the state of Mississippi is by bringing white kids to the state, so that their parents who live outside of the state will notice that this violence is taking place. And so the 60s are a period of intensive racial violence in the state, even as it's also in a period of intensive, stepping up, standing up by the Black community to resist white supremacy. You can see the level of violence with everything from the Freedom Rides as they arrive in Jackson in 1961. There's an agreement with the federal government that they will get to Jackson safely. But when they arrive in Jackson, they are arrested and sent for Parchman State Penitentiary. So, Mississippi is this place that is just inherently violent during Freedom Summer, of course, we know that there is just extreme violence against the young organizers, including the three well known, Schwerner, Chaney, and Goodman who are murdered simply for investigating the burning down of the church. So this is a place with extreme state violence in opposition to the liberation movements of African Americans and again something that we've seen for centuries. Then you put alongside that, that the city of Jackson is desegregating its schools that very year. 1969-70 is the year of the desegregation of Jackson public schools. So the white community is very much on edge. And then you add in the story of Jackson State itself, which is a historically black college, was founded to educate the teachers and preachers of the black community, and had always been a place that has been carefully controlled by its all white board of trustees, their budget coming from the state of Mississippi. In 1967, they get a new president, who is as he says, "a different kind of black college president," he says, "we will have a revolution in our books." So he'll use the language of revolution, he's talking about educational revolution. But that kind of thing really catches hold for the young people in the campus is really changing a bit so that by 1970, you'll have for the first time, Miss Jackson State, in her inauguration, or in her ceremonial ball wears African-inspired clothing, they start using the language of black pride, the school newspaper starting to engage with social issues. They, in fact, like other campuses around the nation, have a protest in the wake of the Kent State shootings. So, by 1970, this is a campus that is beginning to see itself as a site for black freedom. If it's freedom through education, nevertheless, a site of Black freedom. And young people are using the language of Black power, though it's still not a particularly activist campus. But that combination of factors that makes it so that it won't take much for the kind of conflagration that happens then on May 14-15th, to take place.

Kelly 13:30

Yeah, and so Jackson, Mississippi today is I think, like 80%, over 80% Black, but that was not the case in 1970. It was majority white still at that point.

Nancy Bristow 13:42

You know, I don't know that figure off the top of my head, but there was a sizable Black community. But I think that makes it all the more threatening to the white community, right? And Jackson State sits just on the western edge of downtown commuters are driving back and forth between the western suburbs, the white, western suburbs, and the white, office buildings downtown and driving through a Black community that houses Jackson State College, going back and forth. So there is just the racial conflict is right on the surface every day on that campus, because they're contending with white motorists who are driving through and yelling racial epithets, or threatening them by speeding through their campus. And the students are really tired of that. At the same time, the white community is feeling particularly threatened because of the emergence of this new mood of black power, and the reality that they are facing federal intervention in their schools requiring them to desegregate. So tensions are high by the spring of 1970.

Kelly 14:39

Yeah, and I think this, this driving through to anyone who has been on a college campus more recently, you don't drive through the middle of a college campus, typically they're, they're sort of set off from the outside world. But this street this Lynch street goes straight through the middle of campus in 1970.

Nancy Bristow 15:00

And It's a major thoroughfare, right? This is a commuting route a four lane road. But they've put in a stoplight right smack in the middle of campus because there had been in 1964, one student had actually been hit and pretty badly injured. She survived, of course. But it was a serious incident led to a lot of protests. So they had finally gotten a stoplight so that students could theoretically cross the street safely. But it really just created a new site for the ongoing sort of pressure point, because motorists might race through a stoplight, they might stop and then speed up or being stopped as they then start up again, would be a moment when racial epithets would be tossed. So the stoplight had not actually solved the problem. And for students, it was really an infringement on their space, I think they really thought of that street as theirs. And yet it was in the possession of these dangerous white motorists for big parts of the day.

Kelly 15:59

So I want to ask you about the the sort of inside baseball of doing history here of taking this event that happened, you know, 50 years before your book comes out, there isn't video, you know, there's not cell phone footage of this, like, like we would have for events today. What are sort of the sources you use? How do you piece these things all together? And it's a contested history, right? Not everyone agrees on exactly what happened or why it happened. So how do you take these different sources and put them together and try to make sense of this event?

Nancy Bristow 16:32

Well, the extraordinary thing is just how much material there is because there is a police tape. There is there was actually a cameraman and his recorder running. So there's no film footage, but you actually have the sound of what happens right beforehand. But there's an extraordinary records. So the campus itself retained records really carefully. So they have an archive on campus that has actually also been made into a microfilm that's held at the Mississippi Department of archives and history. And in that is the sort of campus end of it. So things like "what did the President say, in the immediate aftermath?" Or "what letters and telegrams did he get?" All of that is available to look at. But in turn, all the news clippings are available. You're right, you still don't have a sense, though, from all of that of what was taking place. But then you remember that there were two grand juries, there was an FBI investigation, there was a President's Commission on campus unrest, there was a local investigation of a mayor's committee that included five local lawyers, and there was a civil trial with 3,000 pages of transcripts. So there are an extraordinary number of interviews with the people who were there, right? The law officers, the mayor, the governor, the president of the college, the students, the office, it's all I mean, and they've all been interviewed not once, not twice, but in some cases, three, four and five times. So I had plenty to work with. And then to top it off, to be honest, it also felt like I really needed to talk to the people who had been there, to the extent that it was possible. So the witness interviews in terms of what took place that night, those interviews done, especially by the FBI, and the police, the President's Commission on campus unrest, were essential because this was capturing the memories in the days and weeks immediately following. But to understand the impact of those events, to be able to talk to people. Now, you know, when I was doing interviews, 45 years afterwards, and now 50 years afterwards, really helped me understand the significance of this event in the individual people's lives. So it's sort of a multi layered set of evidence and different kinds of evidence useful for different parts of what I was trying to understand. So what took place that night, those FBI interviews were really helpful. What has it all meant? Having a chance to talk to survivors was really important. How did it come to be forgotten? Looking at how the press covered it was really useful. So different sources helped to tell different parts of the story? In a sense.

Kelly 19:06

Yeah. And so let's talk a little bit about that. The piece of it being forgotten. And, you know, why, why that happened? Do you think that there, that being so close on the heels of the Kent State shooting was harmful to it being recognized for for what it was and being remembered?

Nancy Bristow 19:30

It's such a good question. I think it cuts to different ways. The bottom line of why it's forgotten is because it's white state violence against Black people. It is about white supremacy, and it is about our nation's failure. And here, I really mean the white community's failure to remember the reality that the state has been used against people of color and especially Black people for centuries. This isn't the only shooting that's been forgotten. In fact, it's not even the first campus shooting of Black students. In 1967, a civil rights worker had been murdered right on the border of Jackson State College. Right, very close to where the kids were killed in 1970. Nobody knows about the Ben Brown shooting of 1967. And in fact, in 1968, in Orangeburg, police had opened fire and killed three students and injured 27. Nobody knows about the Orangeburg massacre, and yet there it sits Black students fired on by white officers. So I think Kent State really helps it be seen, because they happen so close together. In fact, I think it gets a great deal of national coverage. It's on the front page of the New York Times, it's on ABC, CBS and NBC in the immediate aftermath, precisely because it follows right after Kent State. I think it also is forgotten because it follows right after Kent State, because over the long haul, it becomes very easy. If you ignore the racial component of the shooting, which again, white coverage tended to do, then Kent State can stand in for all of the campus violence at that spring. And it can be relegated to, as I saw in one, one anniversary coverage of Kent State, there was a little sidebar of others who died. And that's where the Jackson State kids got put. They didn't just die like every other college student who was injured in that sort of violent time period, they were murdered by white officers because they were Black kids. But it's very easy if you can conflate it with Kent State, then you don't need to remember it, right. And you can only do that if you erased the racial component of the shooting.

Kelly 21:32

And what does that erasure do then to those students who lived through that experience?

Nancy Bristow 21:39

In a sense, I think you could argue that they were injured twice. But that's actually been very painful to people that this story is so unknown. And there are a number of folks who have literally made every effort they can come up with, to try to keep the story alive, at least in Jackson, at least on the Jackson State College campus. And they've done so with eloquence and heroism, and, and in some ways, great beauty, because they have continued to fight the fight to keep, what is a very painful memory, alive. And that's why I would say it's actually quite heroic the work they've done to keep their story where we could find it in a sense. But in addition to that, I think it's been very hard because as these national, you know, 30th, 40th, 50th anniversary is happening Kent State gets so much coverage, it's like being victimized a second time and being victimized a second time again, because they're Black. So it has not gone unnoticed that their story is not as well known as that of Kent State. What is hopeful to me is that this year, there was more interest around the 50th, and then this year, the 51st. They were able to get some national coverage for their commemorations this year, which had been very difficult in the past. So, perhaps, that tide is turning because people are finally seeing that this is one part of a longer story and a story that we're paying particular attention to today.

Kelly 23:00

It looks like Jackson State has done more to memorialize the shootings there than Kent State has done on their own campus. You know, closing off that street, so that people can no longer drive through, naming it after the victims of the shooting. You know, it feels like there there might actually be more of a recognition within the institution itself.

Nancy Bristow 23:25

Initially, I think that was really true that Jackson State was really committed to remembering this story. And that was embraced by the administration by everyone on campus. And they worked really hard in the early years to commemorate and as you say, it took some time, but being able to create Gibbs Green Plaza for instance, which is this beautiful pedestrian walkway through the middle of campus now. That probably was facilitated by the fact that the city found advantages to building a new highway that circumvents the campus and actually was really costly for the Black community. But you're right that on the Kent State campus, again, the young people who were involved at the events worked very hard to keep the memory alive. And in their case, though, found great opposition from the institution that after five years wanted it to go away. They were willing to have commemorations for five years, and then they were done with it. But those young people continue to tell the story. And several people were really instrumental in that. I would name Alan Canfora in particular was one of the injured, who really dedicated his life. It was his second job, I would say that to keep the story alive and did that hard work to keep it in the public's eye. Now he passed away this year, so I wanted to name him publicly. What's really fortunate is that in recent years, the institution itself has turned around and is now embracing it as an important part of the institution story. They've opened an amazing visitor center on campus that has the tell us the story of the shootings in its context of the War, of the student movement, of the civil rights era. And so it's been really interesting to watch the dynamic around that Jackson State went through a period when the institutions seem to be backing off. They too, I think, are back to really saying this is really important history. So finally here around the 50th and 51st anniversaries, I think both institutions have seen the light and are embracing the story that their students and their alums have continued to tell all these years.

Kelly 25:25

Tell me a little bit about the Jackson State, for this 51st anniversary, brought back the students from that graduating class. Can you tell me a little bit about what what happened?

Nancy Bristow 25:38

It was an extraordinary event. Robert Luckett, who runs the Marco Walker center there at Jackson State was really heading up this effort brought together a team of alumni, of current students, of people from the institution from all of the important offices, and managed to pull together for the 50th, an extraordinary set of events that were going to cover the whole year kicked off with the Martin Luther King celebration there in January of 2020. And then, BAM! COVID hit. They still managed to host a really significant events on the 50th anniversary, including bringing, by Zoom, many of their survivors together, including the spouse of one of the young men who had died, including a sister of one of the other young men who had died, and really had a powerful event on the 50th. But this year, they were able to follow through with the original plans for the 50th, which was to bring the class of 1970 back to campus to have a formal graduation. They had not had a formal graduation in 1970, but had been sent home. And so finally here on the 51st anniversary, those students were invited back to the campus and right there at the site of the shooting. They walked across the stage and received their diploma. They were addressed by the by the current president of the university, but also by Dr. John Peoples, who had been the president of a college back in 1970. He gave the keynote address. The two families of the young men who had been murdered Philip Lafayette Gibbs and James Earl Green were both there and were able to receive honorary doctorates on their behalf. And it was an extraordinarily moving event. They live streamed it, which was wonderful for people like me who weren't able to be there, and for so many from the class who weren't able to travel because of the pandemic. But it was really an extraordinary and deeply moving event for I think everyone who was able to be in attendance. And again, just it's such an important commemoration of the way that this class of young people kept a part of history alive, and carried that burden of remembering and to have the opportunity then to be acknowledged, for all they accomplished in 1970. And for all they've accomplished since, was really special and very, very important.

Kelly 27:55

So your book came out just weeks before George Floyd was murdered by a white policeman. And that unlike this shooting, unlike many, many other shootings and state violence, you know, in the year since, finally sparked off this, you know, huge wave of people paying attention and protesting. Can you talk a little bit about what, what looking at something like the Jackson State shooting can tell us about why this is different? Why this happened now?

Nancy Bristow 28:30

I'm not sure if it's George Floyd's murder, that helps us understand it. I think it's that in tandem with the pandemic. I actually do think the pandemic was important precisely because it showed us that the violence of our country in terms of its white supremacy isn't only the police officer who makes it so George Floyd can't breathe. But also in this pandemic, we saw writ large the consequences of the inequities of our social economic systems and the reality that healthcare access was so inequitable. And I think that got us to a place where every single day you couldn't ignore it unless you were very intentionally doing so that we have a serious problem with white supremacy that isn't just a day to day simple problem, but this is a life and death issue. That is day to day. Why George Floyd's murder, I think the fact that it was captured on video so that we could actually see, we were forced to watch a person being murdered, right in plain view, and the officers surrounding it, not stopping it, making clear that this was seen as something that was acceptable to do. And then I think the fact that we had had so many other well known murders in recent years, then I would say that Michael Brown's murder really matters. Ferguson really matters. Trayvon Martin being murdered really matters in this context because again, it had brought add it to our attention. Tamir Rice, Breonna Taylor, I could go down the list of names. I think it had been building since the murder of Trayvon Martin. And that perhaps the combination with the pandemic was just enough. Because in some ways what happened to George Floyd is the same thing that happened to Philip Lafayette Gibbs and James Earl Green, and Tamir Rice, and John Crawford and Breonna Taylor. And it is part of a long history that reaches much further back, in fact. It shows a singular disregard for the value of Black life, and a willingness to forget each time that this wasn't new, but that it had happened before to be able to treat each one as a one off. It took real effort, and I think somehow in 2021, it just wasn't possible in some ways for people to continue to do it. And by that I really do mean white people.

Kelly 30:49

Yeah. Is there anything else that you want to make sure that we talked about today?

Nancy Bristow 30:55

I guess I think it's really important to continue to recognize that these shootings are based in a set of stereotypes around Black criminality that we really need to contend with. In other words, they get excused, they get justified, so that you can flip the script and blame the victims. And we need to really watch out for our use of the kind of language that makes that possible. This use of a law and order description for why we have state violence is something we have to contend with. And we really have to counter act. Because this isn't new. It has a long, long history that reaches actually back to slavery. The other thing I guess I would remember, would urge us to remember, is that the trauma of each of these murders isn't only that of the family, but the each time we're traumatizing millions of people, fellow citizens in this country, and that the trauma is real, and it's long lasting. And so that this is a real crisis that needs to be contended with. So we have hard work to do to recognize the ways white supremacy is woven into everything we do. But in particular, we've got to contend with how it is woven into law enforcement and criminal justice in this country. And the way the use of a criminalizing stereotype has allowed us to flip the script in terms of who the real victims are. We've got to stop doing this.

Kelly 32:22

Yeah. So it tell everyone how they can get your book.

Nancy Bristow 32:25

You can get it very easily by going online to your favorite bookshop. Oxford University Press, is always happy to sell it to you as well. And importantly, I would note that if you choose to buy it, I want to be clear that any profits, any of the royalties that I earned from the book, do in fact, go directly back to the commemoration committee at Jackson State College. I'm not making a nickel off of this. The Press, of course, does. But that's how they stay in business and continue to publish important books. So please don't fear that there's blood money involved here.

Kelly 32:55

Excellent. We'll put a link up to that. So that people can find the book. It's a great read, I learned so much. So I really appreciate it.

Nancy Bristow 33:03

Thank you so much. Thank you so much and I appreciate the chance to bring this story up and to lift up the victims and the heroes of that story.

Teddy 33:12

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. You can find the sources used for this episode at unsunghistorypodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on Twitter, or Instagram, @Unsung__History. Or on Facebook, @UnsungHistoryPodcast. To contact us with questions or episode suggestions, please email, kelly@unsunghistorypodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate and review and tell your friends.

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

Nancy K. Bristow

Nancy Bristow pursues research and teaching in the area of 20th-century American history, with an emphasis on race and social change. She is currently researching state-sanctioned violence against African Americans in the Black Power era of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Under contract with Oxford University Press, she is completing the first piece of this project as a teaching text for the college classroom focused on the shootings that took place on the Jackson State College campus, an historically black campus in Jackson, Mississippi, in May 1970. This work builds on over two decades of teaching African American history, as well as earlier scholarship focused on social cataclysm and American culture, including American Pandemic: Lost Worlds of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic (2012). She also published the book Making Men Moral: Social Engineering During the Great War (New York University Press, 1996). Bristow serves on the leadership team of the Race and Pedagogy Initiative at University of Puget Sound, is a member of the Organization of American Historians [OAH] and the Southern Historical Association, and is currently serving on the editorial board of the OAH’s magazine, The American Historian.