Fashion, Feminism, and the New Woman of the late 19th Century

The late 19th Century ushered in an evolution in women’s fashion from the Victorian “True Woman” whose femininity was displayed in wide skirts and petticoats, the “New Woman” of the late 19th and early 20th centuries was modern and youthful in a shirtwaist and bell-shaped skirt.

Earlier fashion experimentation by feminists in the mid-19th Century had failed to catch on and had interfered with their ability to inspire change as they were labeled radical for their sartorial choices. Feminists in the late 19th Century chose a different path, using the popular fashions of the day to appear respectable as they pushed for rights for women. The mass availability of the shirtwaist also helped to democratize fashion so that working class, immigrant, and African-American women were all able to adopt the costume of the day as they made their demands for better working conditions and increased rights and access.

In this episode I’m joined by Dr. Einav Rabinovitch-Fox, author of the upcoming book, Dressed for Freedom: The Fashionable Politics of American Feminism, as we discuss the uses of fashion by feminists at the turn of the 20th Century.

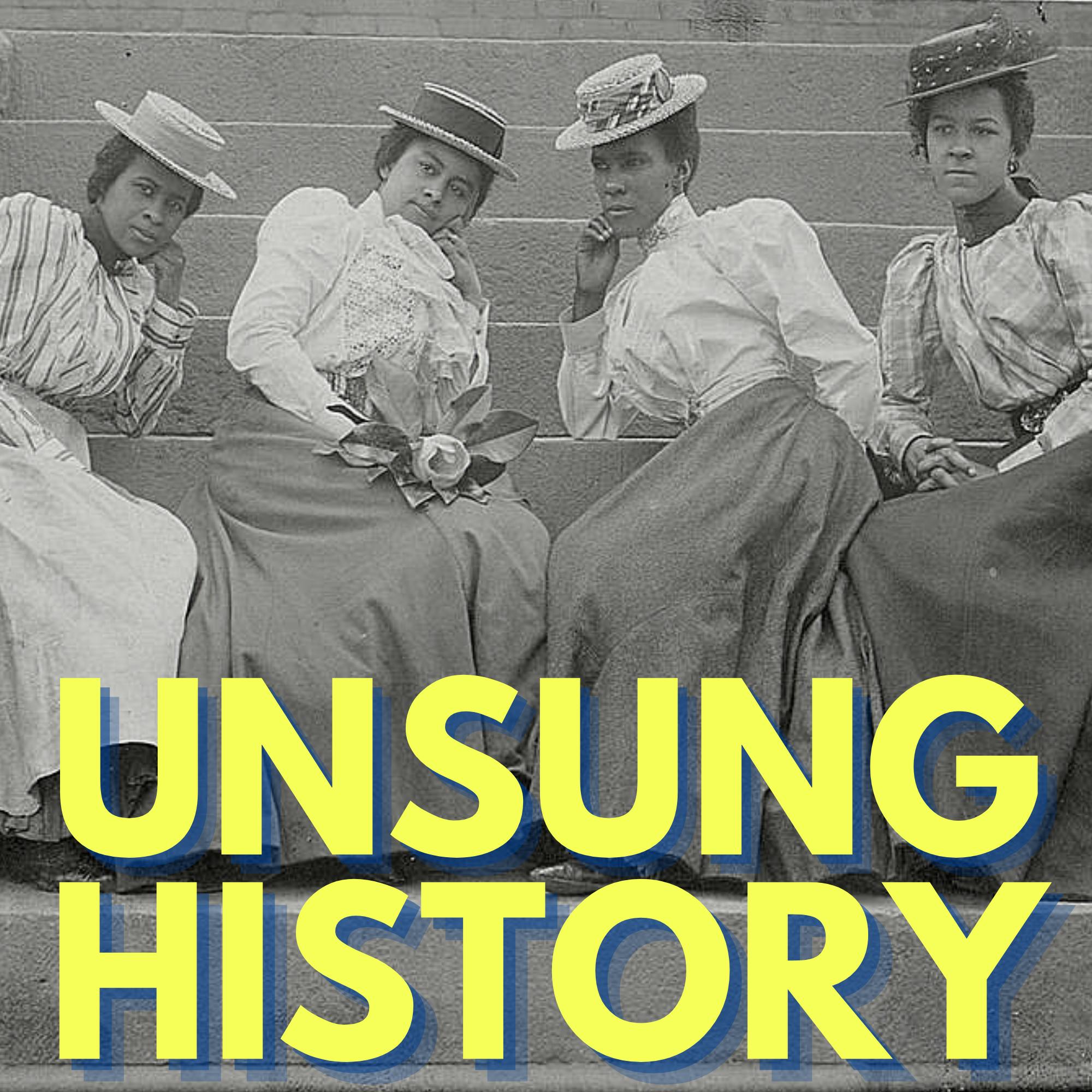

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. Episode image is: “Four African American women seated on steps of building at Atlanta University, Georgia.“ Atlanta, Georgia, ca. 1899. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/95507126.

Additional sources and links:

- “Congresswoman Carolyn Maloney Calls for 'Equal Rights for Women' with Suffragette-Themed Met Gala Dress” by Virginia Chamlee, People Magazine, September 14, 2021.

- “Schools enforce dress codes all the time. So why not masks?” by By Einav Rabinovitch-Fox, The Washington Post, August 30, 2021.

- Beyond the Gibson Girl: Reimagining the American New Woman, 1895-1915 by Martha H. Patterson, 2005.

- “The Gibson Girl’s America: Drawings by Charles Dana Gibson,” Library of Congress.

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Kelly Therese Pollock 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app, so you never miss an episode. And please, tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen too.

Today's episode is about fashion and feminism in the late 19th century. The late 19th century ushered in an evolution in women's fashion from the Victorian true woman whose femininity was displayed in wide skirts and petticoats to the new woman of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, who was modern and youthful in a shirtwaist and bell shaped skirt. American illustrator Charles Dana Gibson published a series of drawings of the new woman, which became known as the Gibson Girl starting in a publication in the century in 1890. The Gibson Girl was confident but not radical. She was tall, white and middle class, often golfing or doing other outdoor pursuits. She personified the new freedoms women were beginning to enjoy, but she was still corseted, and wearing a long skirt. One of the signature items of the Gibson Girl ensemble was the shirtwaist. The shirtwaist, the women's version of the men's dress shirt had been introduced as early as the 1860s. But it was in the 1890s that its popularity really took off. Because the shirtwaist could be both mass produced and also sewn by household sewers from paper patterns, and because the shirtwaist could be made from a range of materials, it was available not just to middle and upper class women, but to working and immigrant women, and also to Black women who could order shirt waists from mail order catalogs, if they weren't welcomed into department stores. The shirtwaist and skirt ensemble worked to democratize fashion in a way that was new to the era. Back in the middle of the 19th century, feminists who were advocating for the women's vote, like Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucy Stone, Susan B. Anthony, and Amelia Bloomer, had adopted a style of dress known as the Turkish dress, and eventually as bloomers, which were divided garments for the lower body, essentially wide pants. The fashion was so scandalous that it detracted from their effectiveness as reformers, and they returned to corsets and long skirts. Feminists at the turn of the century had learned this lesson well, and instead, they adopted the fashion of the time, and claimed public roles without being labeled as radical feminists. The changes and adaptations of the late 19th century were slower and less drastic than the bloomer experiment. But they were important in allowing women greater access to public spaces. In particular, the growing popularity of the bicycle in the middle classes in the 1890s gave women freedom they hadn't had before. The safety bicycle, introduced in 1886, had a dropped frame design that accommodated women's skirts while riding. In 1896, Susan B. Anthony said that the bicycle has, quote, "done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world. It gives women a feeling of freedom and self reliance." Because cycling was done in public, the costumes worn for bicycling were visible to all and had an effect on fashion. In particular, corsets were loosened for bicycling, and some women wore bloomers. Boomers again failed to catch on as popular fashion. So instead, some women who rode bicycles wore skirts that were divided, but looked like regular skirts from the outside. Most popularly, women cyclists wore shorter skirts that generally stopped right at the top of the boot. Some women enjoyed the freedom and comfort of the shorter skirts so much that they wanted to wear shorter skirts all of the time. They pointed especially to the difficulty of walking down a muddy or snow covered street with long skirts, and health concerns that came with dragging wet dirty skirts with them everywhere they went. In 1896, a number of society and career women in New York formed a club called the Rainy Day Club, to, quote, "secure health and comfort by sanitary methods of dress, and at the same time to encourage the use of costumes that are genuinely artistic, graceful and modest."

Many of the women were younger, under 30, and represented the new woman in the workforce. The Rainy Daisies, as they became known, drew a lot of media attention, and they expanded to branches in several other towns in New York, along with Somerville, Massachusetts, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Ann Arbor and St. Louis. In addition to shorter skirts, club members also pushed for other practical improvements to women's fashion, including lighter fabrics, higher boots, and even pockets defined as "women's greatest lack and a major hindrance to women's progress." According to Dr. Einav Rabinovich Fox, for the new woman of the 1900s, the shirtwaist and the short skirt became the epitome of and the terrain from which she could negotiate political, racial, gender, economic and social equality. Yet it was not the shorter hemline of the skirt, or the looseness of the shirtwaist, that made the Gibson Girl ensemble liberating. But it was the meaning that women gave the outfit, using it to reflect their own interpretation of fashion. Indeed, the new woman and her fashions reflected her generation, women who were beginning to do away with ideas of gender hierarchy, and to claim new statuses and freedoms, but who were not completely ready to denounce the traditions with which they grew up. To help us understand more, I'm joined now by Dr. Rabinovich- Fox, author of the upcoming book, "Dressed for Freedom: The Fashionable Politics of American Feminism," which is also the source for much of this introduction. So hi, Einav. Thanks so much for joining me today. And I wanted to start just by asking you how you got interested in fashion history?

Einav Rabinovitch-Fox 7:43

Yeah, thank you for having me today. It's great to be here. And I wasn't so interested in fashion history, but more in kind of, like, interested in history of feminism and feminist movement. And what I was always kind of, like, bothered by I have to say was like, why feminists have such bad PR? Why they have this reputation that they're ugly, and that are not fashionable. And this all I'm, I believe in, in women's equality, but I'm not a feminist because I like to wear high heels and makeup and I was like, but why are these two kind of like, where does that come from? Why kind of like feminists have such a bad reputation. And when I started to kind of like look at suffragists and feminists in the early 20th century, I was really surprised to kind of like to see an all the cover cover in the magazines. And, you know, everybody taught like, how beautiful they were, and how, you know, how good they looked, and how, and they themselves kind of like were very obsessed with kind of like fashion and an appearance. And I was like, well, so maybe there's something here that we need to kind of like, it's more of a complicated story to tell. Yeah. So I kind of like, went and looked back and tried to unravel this mess that feminism and fashion are kind of like, opposing forces. And I was trying to kind of like, wait, wait a minute. No, it's actually not as black/white as we like to think. And I really, you know, I was really surprised and happy that, yeah, that I guess, like, you know, women just like to look good and talk about fashion. And feminists were not so different in that regard. Not 100 years ago, and not now.

Kelly Therese Pollock 9:44

Yes. So this this early history that you start with in the sort of starting in the 1890s, and full disclosure, I watch a lot of Murdoch Mysteries. So this sort of fashion was very familiar to me. I was like, "Oh, yes, that's exactly With the women ere wearing," so this sort of Gibson Girl look. When you were writing, especially that section but but the whole book that you're writing, what are the kinds of sources that you're looking at? And it seems like at least some of this gets to be sort of looking at magazines and pictures, which, which seems kind of fun. But, you know, what are the ways you sort of can can unravel this story a little bit?

Einav Rabinovitch-Fox 10:23

Yeah. So, so yes, reading magazines, it's, I mean, I have to say that when you're doing it for research, it stops being fun, to certain degree, just the amount of Vogue that I can read kind of like, okay, this is, but yeah, so many, so a lot of women's magazines, but a lot of visual reading. So there's a lot of illustrations and sewing patterns. And you know, even unfortunately, you know, for some, especially kind of like the older period, kind of like that, it's hard to find actual clothes, because costume collections are usually kind of, like have this class biased into into them, you know, people who give their clothes are oftentimes rich people. So it's kind of like skewed costume collection towards kind of like, the celebratory, right, and kind of like, you won't donate the t- shirt that you would go to sleep with, right, you can donate your wedding dress.

Kelly Therese Pollock 11:29

I should donate my T- shirt to a future collection.

Einav Rabinovitch-Fox 11:33

Historians of the future will actually appreciate that, but kind of like, right, people don't donate usually their everyday clothes. And that was what I was interested in. And especially for, you know, groups like African Americans, or working class people that are oftentimes not so much represented at costume collections. So, so that was a source, but it kind of like being a source for certain things and, and not so useful for the things that I was looking. But on the other hand, people in the early 20th century and you know, late 19th, really wrote about, and which is nice, I mean, not all the time, you get, you know, manifests of like, "Today I woke up and decided to," you know, because people don't do that. But, but feminists do mention it in their diaries, and even in their public writings. And women themselves, I mean, you know, every time they bought new clothes, right, like, it's, it's this thing, these little things that you tell your friends, or you tell your diary of like, "Oh, today I went shopping, it was so great." So that also gave you kind of an insight to what these people wore, that was not all the time what you know, you've seen in magazines. But it gives you kind of like the understanding. And photography, a lot of photographs, as well were very helpful.

Kelly Therese Pollock 13:02

You talk about the the sort of Gibson Girl outfit and the shirtwaist as being not a revolution, but an evolution. So can you talk a little bit about what what it evolved from, you know, what, what were people wearing prior to this? And, you know, they're still wearing corsets, you know, it's it's not like, totally a, you know, radical type of thing. But you know, what, what are the ways that this sort of outfit is a little bit simpler or more versatile for these women?

Einav Rabinovitch-Fox 13:32

Yeah, so I mean, for women, for a long time, there wasn't really a ready made industry or what we call an industry, just because that women's bodies are more difficult. The standard designs, as we all know, not just no one size 10 that fits all, so the mass made fashion really started with men's clothing, and really, with the Civil War, with the need to make uniforms in large quantities. And that became kind of like, "Oh, yeah, men, it's not not a problem, like we can do that". But for women, it was really difficult. And at first, it was really about like wearing a dress. So for a dress, it really need to be fitted to a body. I mean, even if the dress has a few parts, it's not something that you know, everybody can and it's not something that you can wear on your own. Oftentimes, you know, you need someone to help you get dressed, whether it's you know, to pull the corset, or or to kind of like button, the buttons on your back. You cannot do it on your own. So, you know, it's not always your the servants, but it's sometimes your mother or your sister or you know your husband, but it's really is debilitating in some sense that you can't even dress and undress on your own. And and what the the shirtwaist did was really it's a kind of like a female version of a male shirt. So it was easier to standardize, because it was kind of like in a loose feed that was gathered at the waist. So kind of like creating this pigeon - like image, but it was easier to standardize and then the industry could not only mass manufacture it, it but also kind of, like start to kind of like think about sizes, and maybe we can group women into sizes and then to, to have it all people to to buy it, and it was really ease about buying clothes that really kind of was starting to take off in this period. Because a lot of people made their own clothes, or, you know, if they could afford it, they would send it to a dress maker, but it wasn't something that you bought. And this shirtwaist was really the first item that women bought. You know, it had grades for sure, like you could buy a shirtwaist for $50, and you could buy one for 15 cents. But all of these women could buy this shirt to look fairly the same, right? It's the same styles, even if it's not the same quality. And they could look you know, respectable. It was very convenient. So they could go to work with they look respectable enough, s they could you know, go out of the town and do stuff. You won't go to a you know, a dinner party, wearing a shirt- waist, but for everyday wear it was definitely you know, not something that you need to change. So you could go through the entire day with it. And even if the turnout rate was very fast, especially for kind of like the cheaper, shirtwaist. So you could, you know, you could wear them out. This is why part of also why we don't find a lot of shirtwaists in costume collections, because people did, wear them out, and then buy a new one. And it's not that much of a of an expense that you know, like a dress you would buy. Oftentimes, especially if you're coming from you know, working class, you will have a really good one dress that you wear all the time for, you know, for everything. But you know, the shirtwaist is something that you can wear and wear out more often. And you can replace and then you can also change, you know, for the changes in fashion of shirtwaists were not that, that extreme like you add, like enforcement or kind of like, or changing the height of the collar. It wasn't maybe the sleeve, right? In the mid 90s sleeves kind of like go in really big. But but those are kind of like minor changes, but you can even do it yourself. And we need to remember, women at the time knew how to sew. That was not kind of like a rare skill. And most of kind of like garment workers, right, that's was their job. They knew how to kind of like, even if they couldn't afford oftentimes the shirtwaist that they were making, they could steal you know, a piece of lace from the factory and then kind of like sew it to their own shirtwaist. So they knew how to kind of like maneuver the system to become fashionable. And then they can present themselves as part of the trend, part of kind of, like, part of this world of being fashionable, I mean, and it's something that we see even today, right? We don't you know, when we wear H&M and Zara who are basically knock offs for more couture kind of like fashion, but we all kind of like wear the same styles and kind of like have this common language in terms of fashion that that later on is being translated into political activism. And later on when garment workers will go on strike, they can get that solidarity from the middle class and the rich women of New York and then standing with them in the picket line and getting arrested with them. Because in some to some degree, they look the same. So so there is also allowing for this cross class and cross race solidarities that are based on kind of like this commonality of fashion.

Kelly Therese Pollock 19:39

Yeah, and this this cross race piece is so interesting. So the the Gibson Girl of course is you know pictured as white and you know, fairly well off lady of leisure kind of thing. But you know, you're talking about the the working class who are able to to adopt this look as well. But then also the African American women are able to take this look, and you have these sort of great moments where people like Mary Church Terrell are talking about needing to sort of look respectable, you know. Can you talk about that the race piece of it as well?

Einav Rabinovitch-Fox 20:13

Yeah. And it is, there is this politics of respectability that, and especially for African Americans who are barred from not just you know, civil rights and equality, but also, many of them really need to fight for their humanity. And it's really, for them looking, respectable, looking fashionable, is hard. It is a political statement. It's saying, "I'm as good as you" to some degree, and there's a lot of emphasis in looking good and putting the best, you know, face that they can have towards white society and kind of like, you know, believing in the visual power, right, of, of photography, of appearance that if you look at us, and you look how beautiful we are and how well dressed we are. So people will say, "Oh, maybe you know, they're not, they do deserve the rights they ask." And the Gibson Girl, again, because the shirtwaist becomes so prevalent, allows them to tap into kind of like, this leisurely, this collegiate image that the Gibson Girls also have and say, "Here, look, our students are also you know, dressed like a Gibson Girl. We can also claim this collegiate image that we have, that's kind of like, you know, that everybody's doing, right?" And get that acceptance through that. And even though that sometimes, maybe African Americans like will go more on the conservative side or kind of, like, will try to kind of like, up it up, you know, in terms of embroidery or in terms of color, it's still kind of like maintained, like, within the boundaries of what is fashionable. And you can see it even later on in the, you know, in the 20th century, when feminists in the 70s are kind of like, you know, foregoing any kind of like, signs of femininity and thinking like, "This is oppressive, we don't want it" and, and Black feminists say, "No, like, you know, maybe for you to wear, you know, jeans is liberating. But for me who are used to kind of like those hand me downs throughout the year, I'm not like gaining any liberation from looking like a slob, or looking, you know, not feminine. For me being you know, being acknowledged as a beautiful woman, that's the liberating thing. That for me is the is really the political statement, not kind of like rejecting those ideas." So it's kind of like an interesting dynamic of how fashion functions differently for these groups?

Kelly Therese Pollock 23:14

Yeah, definitely. So the the initial sort of Gibson Girl look is, you know, still a very long skirt, but you you talk about these Rainy Day Clubs. And then I think they call themselves the Rainy Daisies, who are sort of working on raising the hemline of the skirt. So can you talk about some of what their motivations for that are? And you know, they may be less successful than the Gibson Girl look, but still pretty successful in popularizing this idea.

Einav Rabinovitch-Fox 23:42

Yeah, and, and it's, it's important to think that that again, like the connection between feminism and fashion is is really going like way back. And kind of like by the kind of like, the more known example that we might know is the bloomer, right. But that's a total fiasco and it's really a trauma for many, for many feminists and other women. They were like, "No, like we don't want to even get associated with this." And they do try to find something that will be comfortable because the bloomers were at the end of the day, very convenient and comfortable and allowed mobility, but they didn't look good on you. So so the Rainy Daisies are kind of like, "We want to have it all. We want both to have like convenient clothes that we can go out and about the entire day without like dragging our skirts in those filthy streets, and streets were filthier in the 19th century than they are now, "and not be worried about getting sick and and getting clothes dirty." And the bloomers for them was not an option. But what was an option was kind of like this, what we call short,which was not short, but basically mid calf, but it was shorter bicycle skirt, because at the time, bicycles are really becoming the trend and some are wearing bloomers to ride the bicycle. But what really picks up is this shorter bicycle skirt that allows women to ride those bicycles without falling and getting the skirts tangled on their bikes. And they say, "Oh, look, this is kind of like can be a good solution for us." And so they do adopt those shorter skirts, some of them even go very close to the knee. They never, they never get to the knee. That will happen in the 20s. But, but they kind of like say, "Well, you know, this is part of fashion. And we kind of like everyone should wear according to their own tastes, right?" They really emphasize that it's, it's like it's not a decree. It's not like a uniform, they're not forcing anyone. They do it because this is like they feel good about it. And it makes them look good. And it really is fashionable, because hey, look at all kind of like those women riding their bicycles. So kind of like why can't we just wear them off the bicycle. But it's interesting that hemlines are kind of like, you know, will come back, right, the question of hemlines, will come back throughout the 20th century. You know, it begins with Rainy Daisies. But in the 20s, there will be a big hoorah about kind of like this attempt to lengthen the skirt that at the time was at knee height. And women were like, "No, like, we're not giving it up with just like, we won, we fought to, to win suffrage, and we fought to knee height skirts, and we're not going to give it up so quietly," and it's interesting. And it is a fighting battle. And we see it again in the in the late 40s, and again with kind of like the miniskirt in the 70s that women are kind of like with especially with hemlines and kind of like, I'm very careful not to say, "Oh, this is a feminist fashion," or "This is a feminist style". But I think it's interesting how kind of like, this question of hemlines and mobility and comfort is really coming back and women do find shorter, the shorter lengths, kind of like more liberating.

Kelly Therese Pollock 27:47

Yeah, so it's sort of leading into the the next question I was gonna ask anyway about this sort of who, who is driving these fashions. And so what we're talking about at the beginning with the Gibson Girls, you know, Gibson is a guy, of course, who draws this drawing of a Gibson Girl, and there are other people drawing similar drawings. But the the kinds of things you're talking about now, this is very much women saying, "No, you're not gonna do that to us, we're gonna keep wearing things like this". So what does that push pull look like in the the late 19th into the 20th century about sort of, who is driving his decisions about fashion?

Einav Rabinovitch-Fox 28:22

So right, it's always kind of like a dialogue between the industry and and kind of like women that are kind of like, they are the consumers. They have the money, and they are making a decision. And sometimes they do vote with their purse. And it's interesting, because at first, again, with the kind of like industrialization of this and the mass manufacturing of this industry, the industry is kind of like is in favor of this feminist argument for simpler clothes for simpler silhouettes, because it's easy to manufacture, it's much easier to standardize. So all those arguments are actually very much aligned with also economic interests that the industry finds useful. So at the beginning, right, where the clashes begin is when the industry says, well, we need to change the fashion because we need to make women buy new clothes. That's that's like, right, that's how the fashion works. And then that's how we get kind of like right, seasons, and that suddenly, you know, and trends that it's all about making us buy new clothes. But women are pushing back against that and they're and sometimes the industry caves, and you know, and don't go as far as they planned with their plans, because women in the end are the ones who are making those consumer decisions and as they will go to the 20th century women will have more and more consumer power, and they know how to use it. They're very organized, whether it's with consumer leagues, women do organize around those issues. And also around, you know, they're organizing boycotts, they're organizing protests against skirt lengths. So so they do know to kind of like, don't touch my wardrobe, right, type of thing, but also kind of like, as we are progressing, kind of like the 1920s, the 1920s, and kind of like, into the 40s, the fashion industry is really becoming very feminized. You know, the people who rule, you know, there's always like the big man, retailers are men, but kind of like, if you even look at couture designers. This is the era of Chanel, of Lanvin, and all of these, they're French, but they are kind of like setting the tone. And they're women and they're kind of like pushing themselves that kind of like they're making clothes for women like themselves. And even in retail, because fashion was seen as kind of like this feminine occupation, it's, it really becomes a career. And by 1940, it's really kind of like the place where women are getting into kind of like executive positions and gaining power. So you see them, all of the big editors are women of the women's magazines. We have Dorothy Shaver and Lord and Taylor and other department stores. We have fashion designers, in Hollywood, there's a lot of women working at the studios. So and all of them are coming kind of like in a sense of like, we want to design clothes for ourselves, for for women like ourselves. So yes, it's very much white women and young women and thin women like themselves. So it's not necessarily inclusive in that sense. But but it is more of you know, it's not a male designer who's like, "Now you need to wear this very uncomfortable thing, because I decide it's fashionable."

Kelly Therese Pollock 32:20

Yeah, clearly everyone has to buy your book, because we could just keep talking all night. But we're not going to keep talking all night so everyone just has to go buy the book so that they can can get the rest of this. But I definitely want to make sure we have a chance to talk about sort of the the current events in in fashion and politics. And of course in the your your history doesn't get all the way here. But in your epilogue, you talk about things like the pussy hats and you know, sort of ways that that politics and fashion go together even today. And of course, we have this fairly recent example of this with the Met Gala. And you know, everyone focused on AOC's dress that said, "Tax the Rich" on the back, but Carolyn Maloney's dress was just amazing. Can you talk a little bit about Carolyn Maloney's dress and you know, sort of how that really references the these earlier eras of feminist fashion?

Einav Rabinovitch-Fox 33:16

Yeah, no, I also really liked her dress, because I think it was, you know, and the theme was American Independence, I think really fit well into kind of like, really an homage to not just the ERA, which is her thing, but but to sufferagists in general. And kind of like the use of suffrage color, though, a white, purple and gold and green with, although it's the British suffragists who use that green, but really to think about and I think, and again, like suffragists were very aware of their kind of like that they wore their politics, literally. And I think what she did was very much kind of like, right, similar to the sashes that suffragists wore was really interesting, and how this visual language that really sufferagists pioneered are still with us and are still kind of like, you know, you can still play with this imagery. And really, I think it's really fascinating how, at even today, like, I don't think a woman politician can, you know, cannot wear white. It became kind of like this color, because it was so much associated with suffrage. You know, we saw it with Kamala Harris when she was giving her inaugural speech after she won and it almost seem like you know, even the "Tax the Rich" was a white dress and it seems like you know, today, if you want to show that you're a politician for women's rights, you have to wear white. So I think right, like, Maloney's dress was kind of like hooha and kind of like really push it home. And that's part of the Met Gala, right. It's to do it in the extreme. But But even in kind of like, you know, during Congress hearings and kind of like the State of the Union, we still see those legacies. And I think there is more understanding that you can do a lot with fashion. I mean, there's certainly some women politicians who really, like AOC, really kind of like understand it, but Nancy Pelosi, you know, there are others who are really good at understanding the power of fashion. And I think, you know, going back to the feminists and the Gibson Girls who are saying, you know, this is not an oppressive thing, like, you know, if we are going to be judged by how we look, and how we dress, then at least we'll, you know, make it an empowering thing. And we'll play it and we'll make use it to our favor, and to advance our own agendas while looking beautiful. So like, you have nothing to say against it. And I think that is maybe the most important legacies that that the feminists of a century prior left to us.

Kelly Therese Pollock 36:21

So tell everyone how they can preorder your book so they can see all of it. And you know, we we skipped over whole bunches of history that's included in the book, that's also super fascinating.

Einav Rabinovitch-Fox 36:31

Yeah, you can order it through Amazon or any other website that sells books, but also through University of Illinois Press through their own website, just Google "Dress for Freedom." And I'm there.

Kelly Therese Pollock 36:48

Excellent, and I'll put a link in the show notes too, so that people can see that. And I'll also put in links in the show notes to some of these images that we have talked about, because you really do need the images to understand some of this. And that's, of course, part of what is so fun about your book is there are lots of images to just sort of reference what you're talking about.

Einav Rabinovitch-Fox 37:08

Yeah, podcasts that, it's kind of like, not the best medium to talk about fashion. But I'm glad we did.

Kelly Therese Pollock 37:16

Is there anything else that you wanted to make sure we talked about?

Einav Rabinovitch-Fox 37:18

What I really want people to take from my book is really to think about fashion seriously. And you know, and again, not that each of us are, you know, getting up in the morning and writing our own manifestos for what we wear. But what we wear matters. And I think we need to, you know, stop with this kind of like, "Oh, like, if you're a true feminist, you shouldn't, or we shouldn't reduce conversation to clothes," because I think we should talk about clothes, like there is a room for that. And even for the only reason that it's fun, and it's pleasurable, and you know, and we also need to find joy, and in the life and in the archives and in our activism, and not just to talk about everything that is bad in life.

Kelly Therese Pollock 38:11

Feminist are allowed to have fun.

Einav Rabinovitch-Fox 38:14

Really, to think about, not that only clothes matters, but also how I hope people will take it to their own private life.

Kelly Therese Pollock 38:24

Excellent. Einav, thank you so much for joining me. This was a really fun conversation for me. And I you know, I kept thinking about it. You said the Murdoch Mysteries, which of course they're, you know, this sort of late Victorian era, but I also watched things like Miss Fisher and so you know. I watch a lot of murder mysteries, obviously. But you know, I watched them through the decades and so I a lot of this fashion was very familiar to me, and it was really neat to sort of think about it more seriously.

Einav Rabinovitch-Fox 38:52

Yeah, thank you. It was really fun. I really enjoyed it.

Teddy 38:57

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. You can find the sources used for this episode at UnsungHistoryPodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on Twitter, or Instagram @Unsung__History, or on Facebook at Unsung History Podcast. To contact us with questions or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistoryPodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate and review and tell your friends.

Einav Rabinovitch-Fox

I am a historian with a PhD from New York University, specializing in 20th Century U.S history, with a particular focus on Women's and Gender History. Since 2016, I have been teaching in the Department of History at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, OH. My research examines the connections between material culture, politics, and modernity, particularly in the ways in which visual and consumer culture has shaped and reflected class, gender, and racial identities. I am also interested in the history of print culture and advertising, and their relationships with social and political movements.

My book, Dressed for Freedom: The Fashionable Politics of American Feminism (forthcoming in November with University of Illinois Press), explores women's uses of fashion as a means of negotiating new freedoms and of expressing modern political and gender identities. Using fashion as lens, the book reveals how questions of beauty and appearance were an important part of feminist struggles and ideology during the long twentieth century.

In addition to research and teaching, I am also a public historian and curator. During 2015-2016 I was the Wade postdoctoral fellow at the Cleveland History Center at WRHS, researching the cultural history of Gilded-Age Cleveland with an emphasis on the Wade Family, while also taking an active part in the museum's public history initiatives. In 2013-2014 I served as a Research Assistant for the Margret Sanger Papers Project. I also served as a co-curator for an exhibition commemorating the Triangle Shirtwaist … Read More