The US-Born Japanese Americans (Nisei) who Migrated to Japan

In the decades before World War II, 50,000 of the US-born children of Japanese immigrants (a quarter of their total population) migrated from the United States to the Japanese Empire. Although these second generation Japanese Americans (called Nisei) were US citizens, they faced prejudice and discrimination in the US and went to Japan in search of a better life.

Joining me to help us learn about the Nisei who returned to Japan, what motivated them, and the challenges they faced both in Japan and back in the US is Dr. Michael Jin, Assistant Professor of Global Asian Studies and History at the University of Illinois Chicago and author of Citizens, Immigrants, and the Stateless: A Japanese American Diaspora in the Pacific.

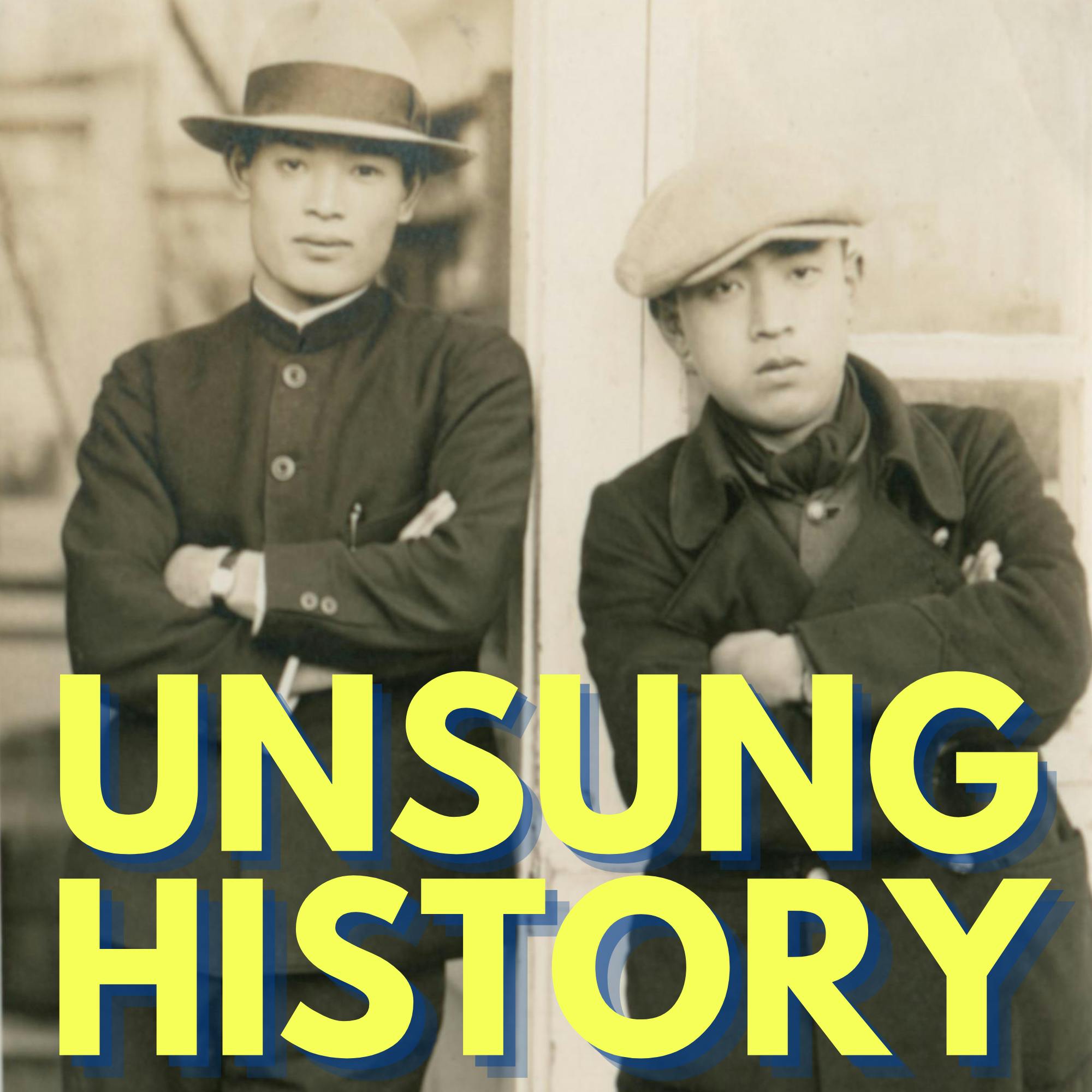

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. Image Credit: “Two students pose outisde a building. Phillip Okano attended school in Japan from 1923-1933,” Courtesy of Okano Family Collection, Densho, This work is licensed under a Creative Common Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Audio Credit: “Tanko Bushi (Coal Miners Dance),” performed by Masao Suzuki, 1956. Courtesy of the Internet Archive. Audio is in the Public Domain.

Additional Sources:

- “Stranded: Nisei in Japan Before, During, and After World War II,” by Brian Niiya, Densho, July 28, 2016.

- “Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History: Japanese,” Library of Congress.

- “Righting a Wrong: Japanese Americans and World War II,” Smithsonian National Museum of American History.

- “First Japanese immigrant arrives in the U.S.” History.com, March 26, 2021.

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Kelly Therese Pollock 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app, so you never miss an episode. And please tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen too.

Today we're discussing the lives of second generation Japanese Americans who migrated to Japan. The first Japanese person to arrive in the United States may have been a 14 year old fisherman named Manjiro, whose ship was caught in a storm and blown off course. He was rescued by an American whaling ship and brought to Massachusetts. One of the reasons that Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month was established in May was to mark the date that Manjiro arrived in the US, May 7, 1843. Manjiro later returned to Japan and served as an emissary between Japan and the West. Japan had been fairly isolated from Europe and the US, until Commodore Matthew Perry of the US Navy sailed into Tokyo Harbor in 1853. The Meiji Restoration in 1868, which consolidated Japan's political system under Emperor Meiji happened partly in response to the growing contact with the West. Rapid industrialization in Japan upset the social order, and unemployed Japanese people started to look to the US and its booming economy in search of a better life. On February 8, 1885, about 900 Japanese immigrants, mostly men, arrived in Hawaii, aboard the City of Tokyo, brought to Hawaii by the Hawaiian government to work on the sugarcane plantations. The Japanese quickly became one of the largest ethnic groups in Hawaii, and 14% of Hawaiians today are of Japanese descent. After the Japanese government legalized emigration, in 1886, large numbers of Japanese came to the mainland US and US territories. Between 1886 and 1911, more than 400,000 Japanese people immigrated to the US, primarily to Hawaii, which became a US territory in 1898, and to the West Coast of the United States. Japanese immigrants faced much of the same kind of racism and discrimination that the earlier Chinese immigrants had faced. Amid calls for a Japanese Exclusion Act, to be modeled after the Chinese Exclusion Act, the Japanese and American governments formed a so-called "gentlemen's agreement" in 1908, wherein Japan agreed to limit emigration to the US and the US granted admission to families of Japanese immigrants already in the US. In 1913, the California Legislature passed the Alien Land Law, which effectively prohibited Japanese immigrants from owning land in California. Finally, in 1924, bowing to growing xenophobia, the US Congress passed the exceedingly restrictive Immigration Act authored by Representative Albert Johnson of Washington and signed into law in May of that year by President Calvin Coolidge. In addition to putting into effect a quota system based on national origin, the law also excluded from entry any foreign national who was ineligible for citizenship by virtue of race or nationality. Based on previous laws, people of Asian descent could not become naturalized citizens, and thus, as of the 1924 act, could not enter the US. The Japanese government saw this as an insult and a violation of the gentlemen's agreement.

This ban would not be lifted until the passage of the McCarran-Walter Act in 1952, which eliminated race as a basis for naturalization. Although the first generation Japanese immigrants, called Issei in Japanese, could not become citizens, their children, called Nisei, who were born in the US were citizens from birth. Although they were citizens of the United States, the Nisei they did not always feel welcome in the US, and in the decades leading to World War II, around 50,000 Nisei, obout a quarter of the total Nisei population, had migrated to the Japanese Empire. They went to Japan for many reasons, sometimes as kids accompanying their parents on the return journey, sometimes to live with extended family who could care for them while their parents worked back in the US, and sometimes for educational or work opportunities. Around 10,000 of those 50,000 Nisei returned to the US before the outbreak of war. The returnees became known as Kibei, and they, along with the Issei and Nisei, were rounded up and interned after President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. The remaining migrant Nisei were stranded in Japan, unable to return to the US after the Japanese military attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Joining me now to help us learn about the Nisei who returned to Japan, what motivated them, and the challenges they faced, both in Japan and back in the US, is Dr. Michael Jin, Assistant Professor of Global Asian Studies and of History at the University of Illinois, Chicago, and author of the 2021 book, "Citizens, Immigrants, and the Stateless: a Japanese American Diaspora in the Pacific."

Hi, Michael, thank you so much for joining me today.

Dr. Michael Jin 8:48

Thank you so much for having me. I'm delighted to join you. I'm a big fan of your podcast.

Kelly Therese Pollock 8:55

Thank you! So I am really excited about this topic, because it was something I hadn't even realized, that this population of people existed until I read your book. So it was really, really fascinating to me. So tell me a little bit about how you got into this topic and started doing this research.

Dr. Michael Jin 9:16

Yeah, I started this project by looking at the long term consequences of the Asian exclusion movement in the early 20th century in the United States. In particular, my focus was on how the anti-Asian xenophobia intimately shaped the regime of the Jim Crow Era racial exclusion in the American West, and the white nationalist attack on the institution of birthright citizenship more broadly. There were concerted efforts in California and other western states throughout the 1910s, 20s, and 30s, for instance, to strip the citizenship rights of the US born children of Japanese immigrants. So my interest lies primarily in looking at how the anti-immigrant sentiment and various exclusionary legal measures designed to stop the influx of Asian migrants based on the orientalist representation of Asians as perpetual foreigners and a danger to the socio-economic well being of white America, did much more than exclude the immigrant generation from American citizenry. The most consequential impact of the anti-immigrant sentiment and the politics of xenophobia was, and I think it still is, to this day, that the threat to their US-born children's future in this country. And of course, the in the case of Japanese American history. The most dramatic and perhaps well known consequence of this early 20th century exclusion movement was the mass incarceration of Japanese and Japanese Americans during World War II, which is arguably the most widely taught and researched topic in Asian American history. The vast majority of those who were incarcerated were American citizens by birth. The US government justified the mass incarceration based on the existing nativist sentiment that even those US-born citizens of Japanese ancestry were essentially Japanese, and they pose a security threat because they were allegedly loyal to the Japanese Emperor by virtue of their parentage.

So the Japanese American community had an enormous social burden to prove their loyalty to the United States, even as they endured the humiliating experience of being prisoners in their own country. And many of them actively cooperated with the US government's incarceration policy. And the dominant narrative of this history is that Japanese Americans were loyal Americans, and patriotic victims of wartime racism, who nevertheless proved their Americanization through their cooperation with the US government and their sacrifice. And they quietly rebuilt their community after the war and achieved remarkable socio-economic success. And they thrived as loyal Americans and fulfilled the promise of American democracy. That's a powerful narrative. But it is also a quintessential Asian American model minority story. And it depicts the mass incarceration as an aberration largely driven by the wartime racial hysteria. And there is still a popular representation of the United States as a liberty loving nation that has welcomed immigrants from all over the world. It is an emotionally appealing narrative, that means a great deal to many people, including those who may not have benefited from that promise of the American dream. And I was troubled by the fact that the onus was on the Japanese American citizens who were incarcerated during the war without due process, to prove their loyalty and their worth as evidence that this narrative of American democracy really worked. I thought there was something inherently wrong there. And I wanted to look deeper into the history of these American citizens' confrontation with the regime of racial exclusion, well before the World War II incarceration. There is rich scholarship on xenophobic violence, exclusionary immigration laws and judicial measures that excluded Asian immigrants from American citizenry since the 19th century, such as the Chinese Exclusion Act, the 1922 Supreme Court case, Takao Ozawa versus United States, that stemmed Asian immigrant status as the so called aliens ineligible for citizenship and with the Immigration Act of 1924, which shut America's immigration gates on Asians. But I always thought that the US- born children of Asian immigrants have occupied a rather ambivalent place in this history of the Jim Crow Era discourse on race and citizenship in which Asian Americans have been represented primarily as an immigrant community at the periphery of the dominant, Black white race relations.

Kelly Therese Pollock 15:11

So then what was the kind of environment that these US-born children of Japanese immigrants were facing in the US? What is it that they are reacting against, as some of them choose to migrate back to Japan?

Dr. Michael Jin 15:28

So I read historical sources from the first half of the 20th century that demonstrated that there was a concerted movement led by organizations like the Japanese Exclusion League, and the California Joint Immigration Committee to strip US-born Japanese Americans of their citizenship rights. And these groups deployed the popular orientalist construction of Japanese Americans as perpetual foreigners. They claim that Japanese Americans were unassimilable elements in spite of their American citizenship by birth, and they lobbied the state governments to add a clause to alien land laws, which had prohibited Japanese immigrants' land ownership so that the laws would also ban US-born Japanese Americans' access to land. And these groups also led a legislative campaign to take away US citizenship of Japanese Americans and even lobbied the government to amend the 14th Amendment of the US Constitution to get rid of the birthright citizenship clause altogether. And although this legislative campaign did not succeed in its ultimate goal of stripping Japanese Americans' 14th Amendment rights of birthright citizenship, the fierce anti- Japanese sentiment nevertheless manifested itself in systemic racial discrimination that rendered US-born Japanese Americans as second class citizens. So anti-Japanese xenophobia and institutional racism directly contributed to the dismal socio-economic outlook for many Japanese Americans in the American West. The doors to vocational opportunities outside the Japanese ethnic community were pretty much closed to most young Japanese Americans in the United States, including those with college educations and professional aspirations. So it was clear to me that the promise of American citizenship had been denied to Japanese Americans long before the Pacific War. But what struck me even more was that the anti-Japanese sentiment throughout the first half of the 20th century had a bizarre consequence that disrupted the integrity of the Japanese American community well before the war time mass incarceration. From the 1910s to the eve of Pearl Harbor in 1941, one in four US-born Japanese Americans left the United States, and they moved to the Japanese Empire. And many of them were young children who accompanied their parents that returned to Japan and resettled permanently there. But there were also many US-born Japanese Americans who moved to Japan and Japanese colonies on their own to seek socio-economic mobility in the rising Japanese Empire. I read this memoir written by one of these Japanese American migrants who wrote, "We were seeking better lives for ourselves, not in America, but in Japan." I read it as a powerful statement that defied the American Dream narrative, which had completely completely failed these Americans of Japanese ancestry. So that's where I started. I traced their movements and their experiences across national and colonial borders of the Japanese Empire in Asia. Here was a group of American migrants in their parents' homeland, and I explored their stories as an extension of their American lives. These American migrants found themselves in an unfamiliar territory that was intimately shaped by the increasingly volatile US Japan relations that ultimately culminated in a tragic war. So this is a story about a community in displacement. But it's also a story about people who used transnational migration as a powerful way to claim their agency and a way to overcome their rightlessness in their own country.

Kelly Therese Pollock 20:03

Yeah. And so I love that you start the book, before you even sort of get into the the narrative by talking about sources and and language. It's no secret to anyone who listens to this podcast that I love knowing about sources and where this this history comes from. So can you talk some about that because you have a variety of different places that you are getting this information about these these different groups of people who are returning to Japan.

Dr. Michael Jin 20:33

So this is a group of American migrants of Japanese ancestry, who left the American West and move to the Japanese Empire. And they live in a fundamentally multilingual and multi-racial, multi-ethnic and multi-cultural and transnational world of the rising Japanese Empire. And in order to understand the distinct place that these American migrants occupied in the world of the Japanese Empire in Asia, I realized that I had to locate and closely examine the Japanese language sources, the Japanese archives. So I've spent a total of three years in Japan, visiting various archival facilities, including the Japanese Foreign Ministries, diplomatic archives, and other places to analyze the various Japanese language documents that were were enormously informative, and eye opening in terms of these Japanese American migrants' varied experiences in Japan and their encounter with Japan's colonial world. They're encountered with different racial and gender and cultural ideologies of the Japanese Empire. And I also consulted other Japanese language sources such as personal memoir, I also talked to individual Japanese Americans who, who settled permanently in Japan, and also those who returned to the United States and, and I was able to gain great insights from the perspectives that they shared with me.

Kelly Therese Pollock 22:44

So one of the most fascinating pieces of this story is sort of twofold. There's this idea that we think of the United States as sort of the the receiving country of immigration, very rarely do we think of it as the sending country, and certainly not this sort of back and forth, that that's not a thing that a lot of people think about in the immigration story. And then related to that is sort of this this sense of belonging of, you know, who where do these people feel that they belong? Do they feel like they belong anywhere? Do they feel sort of displaced everywhere that they are? I wonder if you could sort of talk about that piece of it, that that sort of back and forth migration that isn't unidirectional? And what that means for people as they're thinking about who they are, you know, they probably don't necessarily think of themselves as Japanese American or American Japanese. You know, it's much more complicated than that.

Dr. Michael Jin 23:47

Yeah, one of the things that the book does, conceptually is to revise the United States as a nation, a national space, and as a nation of immigrants. And I also try to destabilize the positionality of Japanese Americans themselves by reconsidering their subjectivity as an ethnic group, as a race, as citizens, and as children of immigrants, and as a community in diaspora. And I do look at the United States as a sending nation of immigrants. But I think more accurately, what I'm really interested in doing is to disrupt the linear and predictable notions about the so called sending and receiving nations of immigrants, because I'm looking at a group of people who move in multiple directions, who moved back and forth between the US and Japanese Empires, and who found themselves in a dynamic trans-Pacific borderlands between the two countries, so they were much more than just a minoritized group. And the children of immigrants confined it to the American borders. And as transnational migrants themselves, they traverse multiple national and colonial borders, from the Jim Crow American West to the Japanese colonial frontiers, like Korea and Manchuria in Northeast Asia, you know, to the cityscape of Tokyo, and, you know, from the World War II incarceration camp to the city of Hiroshima, and then back to their homes in the United States during the Cold War decades. And their experiences and their struggles for survival were intimately shaped by their social relations with diverse groups of people in both countries. And so, the important objective of the book is to trouble notions about national identity, citizenship and loyalty, which is central to the dominant historical memory of the Japanese American experience, and the scholarship, especially one that centered on the legacies of the World War II mass incarceration of Japanese and Japanese Americans. And I look at the early 20th century, anti-Japanese exclusion movement as a powerful historical force that impacted these American citizens' diasporic consciousness, because many of them saw Japan and the Japanese colonial world as a place where they could achieve the kind of socio- economic mobility that was denied to them in their country of birth. Of course, when they moved to the Japanese colonial world, they found themselves in an unfamiliar and frequently unwelcome territory, that often defied their romantic imagination about their parents' homeland. Many of them, I think, thought that they would be welcomed with open arms by Japanese people. Many of them thought that if they could manage to learn to speak Japanese well enough, they could perhaps do pretty well or at least better than they would have back in the United States. But many of them found out that understanding the nuances of the Japanese linguistic and cultural practices was very difficult. They found that achieving the kind of socio-economic mobility in the Japanese Empire was as difficult for them as it was back in the United States. And others also became disillusioned with the kind of racial violence and racial hierarchy and ideologies in the Japanese Empire, and what they also saw as the increasing signs of Japanese fascism. And there were many Japanese Americans who interacted with colonial subjects like the conscripted Korean workers in Hiroshima.

And they witnessed the kind of vicious social discrimination and racial violence that these colonial subjects had to confront in Japan. And there were also other Japanese Americans who became radicalized while they were in Japan, especially during the Taisho Era, which was the interwar period from 1912 to 1925, which was a period of dynamic social unrest and political liberalism, as well as as well as labor movement, often led by Korean workers and other laborers from Japanese colonies. And they became radicalized by their exposures to these these new ideas in and and political development in in Japan, and they increasingly became disillusioned with the contradictions inherent in their diasporic consciousness, and what they what they had imagined about Japan as their homeland. And so many of them decided to return to the United States before the war. So close to 20,000 of the 50,000 Japanese American migrants, they returned to the United States before the outbreak of Pearl Harbor in 1941. And they became known as Kibei. This is one of the words that I use throughout my book. And they added so much to the linguistic and cultural and political dynamics of the Japanese American community, on the eve of the Pacific War.

Kelly Therese Pollock 30:38

Yeah, although that Kibei group then is the group that that has, in some ways, the hardest time in the internment camps and sort of proving their American loyalty, so to speak, because they have had these additional experiences in Japan.

Dr. Michael Jin 30:55

Yeah. And during the war, many of these Kibei were stigmatized as those who returned from Japan with a cultural baggage of being too Japanese. Many of them spoke English with a Japanese accent because they had been educated in Japan and spent many years in the country, as well as in Japanese colonies in Asia. And after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, in December, 1941, the US government treated these Kibei as a potentially dangerous and pro Japan element within the Japanese American community. And there was even a plan to separate the Kibei, and more specifically the male Kibei bachelors, which is a term used by the US government's War Relocation Authority, which was the agency in charge of managing the incarceration camps from the rest of the Japanese American population, and placed them in a segregated prison camp during the war. And that almost happened. And that was based on the perception that the Kibei, by virtue of their education and their upbringing, and their extended stay in Japan were essentially Japanese in their cultural and political disposition. And therefore they must be perpetually loyal to the Japanese emperor. And these Kibei were also ostracized by their own community during the war. Many among the Japanese American community leaders who cooperated with the US government's incarceration policy, identified Kibei as a group that could tarnish the image of the rest of the Japanese American community as loyal Americans, because of the sweeping representation of the Kibei as essentially Japanese, in spite of their American citizenship by birth. And this compelled many Japanese Americans to reject anything that could be perceived as Japanese and sever their ties to Japan. And this intense rejection of Japan resulted in the active suppression of Kibei's voices throughout the war years and for many decades after the war.

Kelly Therese Pollock 33:22

Yeah. So I wanted to ask, in the title of your book, it's citizens, immigrants and the stateless. And so by stateless here, you don't just mean people who feel like they don't belong either place but people who actually are, we talked earlier about the idea of removing birthright citizenship in some cases that actually happened. So can you talk about the sort of who the stateless are and what that means to lose the citizenship that you're born with?

Dr. Michael Jin 33:52

Yeah, so there were a number of ways a number of ways in which the Japanese American migrants became stateless. And I use the statelessness, both in the legal sense as well as in the cultural and political context. They were stateless in the dominant, US centric narrative of the Japanese American experience. For instance, I write about the struggles of the US-born Japanese American survivors of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima in August of 1945. Hiroshima Prefecture happened to be the place with the heaviest concentration of US-born Japanese American migrants, because it was the place that had sent the largest number of Japanese immigrants to North America since the late 19th century. And the city of Hiroshima had at least 3000 US-born Japanese Americans. So we're talking about a significant number of American civilians who were trapped in Hiroshima, and became victimized by the atomic bomb deployed by the US military, the bomb that was supposed to liberate the world from the evil of the Japanese Empire, and the access powers. And after the war, these American survivors of the nuclear holocaust became excluded from the dominant liberation narrative narrative of the war, the US government has yet to acknowledge the presence of these American citizens in Hiroshima. So in that sense, they became essentially stateless in the post World War II regime of reparations and compensatory justice. Many of these atomic bomb survivors returned to the United States, and they led a movement to advocate for themselves and other victims of the atomic bombing. And they also led legislative campaigns in the 1970s and 1980s, which culminated in the introduction of congressional bills that would require the US government to provide medical care and compensations to the American victims of the atomic bombing. The bills didn't really have the chance of being enacted, and served primarily as a symbolic call for the historical recognition of these forgotten American victims of the atomic bombing. So I use the concept of statelessness in the sense that many among the Japanese American migrants who went to Japan as a way to escape from racial exclusion, and xenophobia, and they have continued to struggle to find a place in the narrative and historical memory of the Japanese American experience. Then there were other Japanese Americans who also lost their US citizenship and became legally stateless, while they were away from home. And in general, there were, there were two groups of Japanese Americans whose experiences expose the the long term crisis that these Japanese American migrants had to confront as a result of the unexpected impact of the US government's Immigration and Citizenship policies during the first half of the 20th century.

And one group of these Japanese Americans who lost their US citizenship while abroad include young Japanese American women in Japan, in the 1920s, who married Japanese nationals while they were in Japan. And they lost their US citizenship as a result of the Cable Act of 1922, which stipulated that those American women marrying the so called aliens ineligible for citizenship were not eligible for the US government's new policy, which had recognized American Women's independent nationality regardless of their husband's nationality. So this loophole had a huge impact on a number of Japanese American women who married Japanese men. And his had a particularly negative impact on those Japanese American women in Japan and Japanese colonies who married non US citizens because they lost they legally lost their American citizenship as as a result and once they lost their US citizenship, because of the 1924 Immigration Act prohibited the legal entry of Asians to the United States, these Japanese American women were stripped of their right to enter their country of birth and rejoin their families. Another group of Japanese Americans who became stateless were Japanese American men who were dual citizens who served in the Japanese Armed Forces during the Pacific War. And, and many of them, they were conscripted into the Japanese military. So they, they were forced to bear arms against their country of birth, often against their will. But as a result of their service to the Japanese emperor, they automatically lost their US citizenship based on the Nationality Act of 1940. And it took many of them pains to recover their American citizenship because the onus was on them to prove that they were compelled to serve in a Japanese military under duress. So both in terms of legal and cultural terms many Japanese Americans have because of their actions and decisions, and sometimes because the forces beyond their their own power, you know, they, they became stateless in a variety of contexts.

Kelly Therese Pollock 41:35

Yeah, it's just, it's fascinating and heartbreaking. I remember reading, you have the story in there of a woman who got married in Japan and then got divorced and tries to come back and join her family in the US and can't, and it's just, it's heartbreaking. So your book is a fascinating read. Can you tell people how they can get a copy?

Dr. Michael Jin 41:59

They can get a copy of my book on the Stanford University Press website. And the book is also available at other online booksellers, both as hardcopy and ebook.

Kelly Therese Pollock 42:18

Great. I will put a link in the show notes as well. Is there anything else that you wanted to make sure we talked about?

Dr. Michael Jin 42:25

I think I guess one more thing that I might add is that so when I was writing this book, there was more recent public debate on birthright, birthright citizenship and the sanctity of the 14th, 14th Amendment, especially fueled by the former US President Donald Trump's claim that he had the executive power to eliminate the birthright citizenship of the US-born children of non resident immigrants. And what one of the things that my book shows is that this debate on the 14th Amendment's birthright citizenship clause and the white nationalist attack on birthright citizenship is far from new. And over many decades since World War II, the racial hostility toward Asian Americans, Latinx Americans, and more recently, Middle Eastern Muslim and Arab Americans have continued to sustain the nativist sentiment that the children of non white immigrants are not worthy of the constitutional protection of their birthright citizenship. And moreover, the representation of Asian Americans as perpetual foreigners has continued to fuel widespread xenophobia as demonstrated by the rise in racial violence and hate crimes committed against Asians and Asian Americans during the COVID 19 pandemic, regardless of their citizenship status. Asian Americans' confrontation with this powerful feature of American xenophobia demonstrates that the anti-immigrant sentiment and various exclusionary legal measures designed to stop the influx of migrants don't simply affect the immigrant generation, and that the most consequential impact of the anti-immigrant sentiment is a threat to their US-born children's future in this country. And the Trump's failed attack on birthright citizenship is only one of the countless attempts to strip those American children of their constitutional rights.

Kelly Therese Pollock 45:08

Michael, thank you so much. This was just a really great read. I'm so glad to have learned about about this group of Americans and I am so glad to have had the chance to talk to you.

Dr. Michael Jin 45:21

Thank you so much for having me.

Teddy 45:24

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. You can find the sources used for this episode @UnsungHistorypodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or our used with permission. You can find us on Twitter, or Instagram @Unsung__History, or on Facebook @UnsungHistorypodcast. To contact us with questions or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistorypodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate and review and tell your friends.

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

Michael Jin

Michael R. Jin is a faculty member in the Global Asian Studies Program (GLAS) and the History Department at the University of Illinois Chicago. He is also a member of the UIC Diaspora Studies Cluster. His research and teaching interests include migration and diaspora studies, Asian American history, transnational Asia and the Pacific Rim world, critical race and ethnic studies, and the history of the American West.

He is the author of Citizens, Immigrants, and the Stateless: A Japanese American Diaspora in the Pacific (Stanford University Press, 2022), which traces the history of more than 50,000 U.S.-born Japanese American migrants across multiple national and colonial borders between the U.S. and Japanese empires before, during, and after World War II. Based on transnational and bilingual research in the United States and Japan, the book recuperates the stories of Japanese American workers, students, travelers, and survivors of war on both sides of the Pacific that redefined ideas about home, identity, citizenship, and belonging at the crossroads of Asian history and Asian American history