Babe Didrikson Zaharias

Born in 1911, Mildred Ella Didrikson Zaharias, who went by the nickname “Babe,” was a phenomenal, and confident athlete. Babe won Olympic gold in track and field, was an All American player in basketball, pitched in exhibition games in Major League Baseball, and won 17 straight women’s amateur golf tournaments, before turning pro and co-founding the LPGA.In a society that didn’t welcome women like Babe, she nonetheless forged her own path and won the hearts of fans along the way.

I’m joined in this episode by History Professor Dr. Corye Perez Beene, author of the biweekly newsletter Awesome American Sports, who makes the case that Babe was the greatest American athlete who has ever lived.

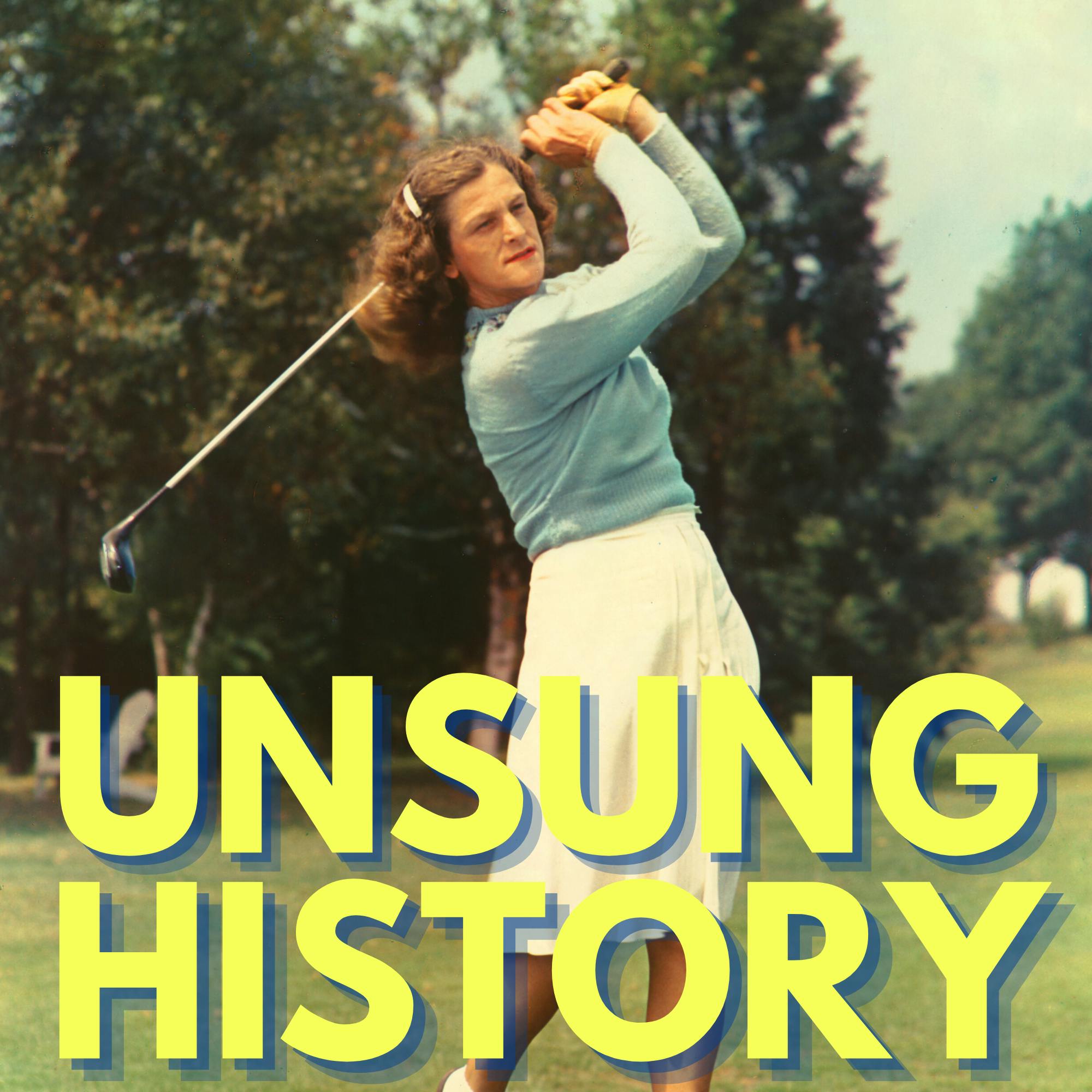

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The episode image is: "Babe Didrikson,” National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Object number NPG.97.211. The image is in the public domain.

Sources:

- Babe: The Life and Legend of Babe Didrikson Zaharias, by Susan E. Cayleff, Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1996.

- This life I've led: my autobiography, by Babe Didrikson Zaharias. New York: Barnes, 1955.

- Babe Conquers the World: The Legendary Life of Babe Didrikson Zaharias, by Rich Wallace and Sandra Neil Wallace, New York: Calkins Creek, 2014.

- “Remembering A 'Babe' Sports Fans Shouldn't Forget,” All Things Considered, NPR, June 26, 2011.

- “The 'greatest all-sport athlete' who helped revolutionize women's golf,” by Ben Morse, CNN, September 8, 2020.

- “Babe Zaharias Dies; Athlete Had Cancer,” The New York Times, September 28, 1956

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Kelly Therese Pollock 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app, so you never miss an episode. And please, tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen too. In today's episode, we're discussing possibly the greatest American athlete of all time, Babe Didrikson Zaharias. Let me start at the top by noting that Babe was a storyteller, and a master of self promotion, who was known to stretch the truth. Even her own stories about herself sometimes contradicted each other. So I've done my best to present an accurate introduction here, but you may well find points of contradiction in other sources. Babe was born Mildred Ella Didrikson in Port Arthur, Texas, on June 26, 1911. She was the sixth of seven children born to Ole and Hannah, immigrants from Norway. The oldest three children were born in Norway before the parents emigrated. When Babe was around four, the family moved to Beaumont, Texas. One of the stories Babe told was how she had acquired the nickname "Babe," which she claimed had happened after she hit five home runs in a baseball game as a child. In reality, Hannah had been calling her "Bebe" from the time she was a toddler. But perhaps Bebe became Babe after that game. Babe's family didn't have a lot of money, and she worked part time jobs as an adolescent. At one point, she sewed gunny sacks for a penny a sack. But she also found time for athletics, even if it meant hurdling the hedges in the backyards on her street. At Beaumont Senior High School, Babe played basketball, becoming their high scoring forward by age 15. Her basketball prowess got her a job with the Employers Casualty Company of Dallas, where she became the star player on their Golden Cyclones team, leading them to the national championship, three years running. Being a basketball star wasn't enough for Babe. In 1932, she represented the Employers Casualty Company at the championships for the Amateur Athletic Union, AAU. Since 1932 was an Olympics year, the AAU event also served as the US Olympic trials. The women's event was held in Evanston, Illinois, in July of that year. Babe was the sole representative from her team at the championships, while most teams brought 20 women to compete in the 10 events. Babe managed an outstanding feat, winning five of the eight events she competed in and tying for first in a sixth. Her team won the championship with 30 points. The runner-up team was the 20 member Illinois Athletic Club, which scored 22 points. The championships qualified Babe for the Olympics. Women were only allowed to compete in three events, and she chose the javelin, hurdles, and high jump, winning the first two and placing second with an asterisk I'll discuss with my guest in the third. Sportswriter Paul Gallico, said of Babe's achievements, "On every count accomplishment, temperament, personality and color, she belongs to the ranks of those storybook champions of our age of innocence." After the Olympics, Babe hung up her track shoes, later famously stuffing the medals into a coffee can instead of displaying them. In February of 1933, Babe's picture appeared in a Dodge automobile ad in the Chicago Daily Times, with a caption implying Babe endorsed the car. Despite Babe's claim that she did not give permission for use of her picture or name, the AAU declared her a professional, which made her ineligible to compete in any amateur sports.

Being a professional athlete was not a lucrative career for women in the 1930s. Babe had to cobble together work on stage and in sporting exhibitions. She played billiards, toured with a basketball team called Babe Didrikson's All Americans, pitched in exhibition baseball games, and joined the tour of the House of David baseball team. She even did photo ops playing football and boxing. But the sport Babe became most known for was golf. In 1933, Babe said to a reporter for the North American Newspaper Alliance, "Most things come natural to me, and Golf was the first thing that gave me much trouble." She probably played up the difficulty a bit, but there's no question that Babe worked hard at golf. She would practice for hours and hours a day, hitting 1500 balls in a day. She told a reporter, "I'd hit golf balls until my hands were bloody and sore. Then I'd have tape all over my hands and blood all over the tape." In April, 1935, Babe entered the Texas State Women's Golf Tournament. Upon her entry, golfer Peggy Chandler said, "We don't really need any truck drivers' daughters in our tournament." Babe went head to head with Chandler and beat her on the 36th hole to win the tournament. Shortly after the win, the USGA banned Babe from amateur competition for three years because of her professional competition in other sports. Babe opted to turn pro rather than fight the ruling, but the pro circuit for women didn't really exist the way it did for men. In January, 1938, Babe met wrestler George Zaharias. By June they were engaged, and by late December they were married. George retired from wrestling to manage Babe's career. Frustrated with the lack of opportunities she had as a pro golfer, Babe decided to sit out competing for a while to regain her amateur status. She took up tennis while she waited, but she was barred from amateur competition since under tennis rules, once you are a professional in any sport, you are a professional in tennis too. She was able to compete as an amateur in bowling, which she found success in, and she played in celebrity golf exhibitions with Bob Hope and Bing Crosby. Finally, Babe regained her amateur status in golf in 1942, and she came back to the game even stronger than she left, winning 17 straight tournaments in a stretch in 1946 and 1947. She won the US Women's Amateur in 1946, and the British Ladies Amateur in 1947, the first American woman to do so, along with three Women's Western Opens. In 1947, she turned pro again, dominating the Women's Professional Golf Association. When the WPGA folded in 1949, Babe, along with 12 other women, founded the Ladies Professional Golf Association, LPGA, which is now the oldest continuously run professional sports organization for women in the US. Babe was president of the LPGA from 1952 to 1955. In 1950 and '51, Babe was the leader on the money list for the LPGA, winning all three of the women's majors in 1950. In 1953, Babe was diagnosed with colon cancer, for which she had surgery. Despite assumptions that she would never compete again, Babe returned to tournament play, winning the US Women's Open in 1954. Sadly, in 1955, her cancer recurred and on September 27, 1956, Babe died at the age of 45 in Galveston, Texas. Joining me to help us learn more about Babe Didrikson Zaharias, and to make the case that Babe is the greatest American athlete of all time, is history professor, Dr. Corye Beene, author of the bi-weekly newsletter, "Awesome American Sports." So hello, Corye, thank you so much for joining me today.

Dr. Corye Beene 9:48

Thank you so much for having me, Kelly. I'm super excited to be here. I'm a big fan of the show.

Kelly Therese Pollock 9:53

Thank you. So I am so thrilled that you recommended that we do an episode on Babe Didrikson Zaharias because I think I had heard the name before, but I think, you know, if you had said "Who is she?" I would have been like, "A golfer?" Clearly, there is so much more. This is someone that everybody should know about. So, so thank you for that. How did you first get interested in learning about her, about sort of studying her life?

Dr. Corye Beene 10:21

Well, I'm what I call a Title Nine baby. And I played a lot of sports growing up in the 70s. And I was lucky enough to play club volleyball while it started. And my coaches told my parents, you know, if she sticks with it, we think she can get a volleyball scholarship. And I did. And when I was in college, I played, you know, I played volleyball, and it wasn't a big deal. You know, we had funding, we got to eat nice meals, we stayed in nice hotels, we, we were in buses, and it was great. And while I'm going and playing volleyball, you know, my mother kept telling me, "Oh, you're so lucky that you get to do this. When I was your age, you know, we didn't get to do any of this." And I said, "What do you mean? This this is this is life. Girls play sports. You get to you get nice meals and stuff." And as I finished college, and majored in history, and then worked on my masters, and then eventually my PhD, I started doing research into women's sports history and found out hey, it wasn't always, you know, rainbows and flowers. And the more I studied, Babe's name came into the picture. My doctoral dissertation is on an aspect of women's sports. There was a group called the AIAW that ran women's athletics before the NCAA, and her name popped up a couple of times. So I started finding out more about her. And that is why I'm here talking about her today.

Kelly Therese Pollock 12:04

Yeah. So I think what's interesting is, as you read about her life, and sort of see where she came from, she's part of this really big family. And it's not like it's a family full of Olympians, and she's not the oldest, you know, and I'm trying to understand sort of how she got to be this this person that she was, that, you know, this just sort of force of nature, you know, where, where that came from, where this athletic ability came from. So I wonder if you could talk sort of about that, about, you know, how her her childhood, her upbringing, like whatever it was, that you think might have contributed that that sort of led to the person that she was?

Dr. Corye Beene 12:43

Well, she was the sixth of seven children, and she grew up in Beaumont. She was born in Port Arthur, Texas, but because of a hurricane, their family moved inland into Beaumont. And she would, you know, she would just participate in sports with her brothers. And we would call her today, you know, a tomboy. She played sports with them. She was always active, and she was a very competitive person. You know, even as a teenager, she said, "I want to be the greatest athlete ever." And she just had this, you know, the motivation was intrinsic. And you notice, you see this a lot with great athletes, that it's not really outward motivations. It's that inward competitive nature. My husband is a track coach, and he is always telling me, "Yes, winning is great, but I hate to lose. And the best athletes hate to lose." And that sums her up perfectly. So as she is in her childhood years, in Beaumont, she just plays everything. Her dad built them, the the kids a gym, in the backyard. And I guess, you know, if you're lifting weights, you're getting stronger. And she as she moves into her teenage years in high school, she plays on every girls sport available at her high school. They did not have track and field. But basketball was her best sport. And back then they played what we would call three court basketball. And three court basketball means there's three zones and depending on what if you're a forward or a defender, you have to stay in a certain part of your of the court. And why women played in that way is because it was too strenuous on girls to you know, run up and down the basketball court like guys did. So even though she's playing this way, she's still the star of the team. Her basketball team never lost a game in high school. Yeah, that's nice for all the athletes out there, right. It would be nice to be undefeated. And so, you know, it was always just, you know, coming from she just always wanted to be the best. She was inwardly motivated. And she was very cocky. You know, I think you see that in a lot of great athletes. And a lot of people don't like that about professional athletes, right? They don't like, they don't like the, you know, the bragging and the braggadocio kind of attitude. But she totally had that. And we see that throughout her life.

Kelly Therese Pollock 15:29

So you mentioned that at the time that she was growing up, that this wasn't a thing that women could sort of get a scholarship, you know, and women couldn't even really make a living as athletes, by and large. So what was her endgame? Did she have an endgame? If she's saying, "I'm going to be the greatest athlete in the world," like, okay, great, but how are you going to pay the bills? What what was sort of the path forward that was available to her?

Dr. Corye Beene 15:54

Well, she just kept going, you know, she would go from one sport to another. So after high school, she didn't complete high school, because there was a gentleman who owned an insurance company in Dallas, called the Dallas Employers Casualty Company. And back in the 20s, and 30s, insurance companies would hire women to be secretaries or typists for them, and then they would play sports. Now, I know, some of the listeners are thinking, "Okay, what's the rationale for that?" They thought athletes were better workers, and they are trying to make more publicity for their companies. You know, I guess insurance is not something that you think about, oh, let's go buy insurance today. I mean, you need you need, you need that publicity. And so he found Babe, because, you know, she was a star. And he hired her to be a typist working for this insurance company. And he paid her $75 a month, okay, and we have to remember that this is the very beginning of the Great Depression. And the fact that she can earn that much money, especially as a woman is going to be a big deal. And I'm gonna, you know, keep I'll continue to talk about how the Great Depression that all this money she's going to make. So she starts working for him, they form a team, they play in AAU, she scores about 30 points a game. And she moves from a three court way of playing to half court. So, you know, still, we're not playing full, normal basketball as we know it today. And as she gets to get all of this publicity, she loved the publicity. She loved the sports writers talking about her. She craved it, she fed on it. And this is really what probably, you know, propels her to ask the gentleman that got her on this team, "Hey, why don't we make a track and field team?" She had just seen the Olympics. So in the 1928 Olympics, she saw women competing. And so she's like, okay, you know, basketball's, good. But wow, Olympics, track and field, you know. She, it's like she had a vision, she could see forward that she would be good. Or, you know, she hoped she would be good at this. So she will compete in 1932 at the AAU national championships. She's the only person from the insurance company that competed. Now, the purpose: more publicity. Wouldn't it be interesting if the newspapers covered her as a one-person team? And of course she, she was something else. Let me tell you, I'm gonna read you everything that so she competed in eight events, won six of them. She made four world records: in the javelin, 80 meter hurdles, the baseball throw, and the high jump. She made a United States record in the shotput, won the long jump, and was fourth in the discus. Now, I don't know about you, but I'm tired just thinking about that. So she competed in all these and her one-woman team won the competition. And it boggles the mind because for all of the listeners out there who know anything about track or you know, sports, think about all of the practice. Think about just you know, God-given something, God-given strength, and now maybe some people are thinking, "Oh, well, she must have been quite a, you know, a physical specimen. She must have been six feet tall," and she was five' six".

And you know, because maybe some of us are thinking, "Well, she was a basketball player, she must have been tall. Basketball players are tall." And she wasn't. After she won all these things, this is how she got she qualified for the Olympics. The AAU track and field championships are today what maybe we would call the Olympic trials. And so she leaves there, she goes immediately to the Olympics that were luckily, in Los Angeles in 1932. And there, of course, she puts on another show. Now, the IOC, the International Olympic Committee only allowed women to be in three events, because of, again, we can't it's too strenuous. It's too much of a burden on women to, to do too many events. So there is still a lot of sexism even though women are participating in sports, it's very limited. And there are not a lot of people that think that women should be competing period. So these people that are in opposition to that have a lot of effect on the IOC. So they told Babe, "Sorry, girl, three events, and that's it." And she picked the javelin, 80 meter hurdles, and the high jump.

Kelly Therese Pollock 21:21

Three completely different kinds of events!

Dr. Corye Beene 21:24

They are and like I mentioned a minute ago, you know, all the practice. Today, if there were coaches that could see that you're doing all these events, they would say, "Hey, you got to take a timeout." Overtraining is like the enemy of an athlete. Too much practice, too much training is just as bad as doing, you know, not enough because, you know, you got to save your body. There's, there's, we know the science now regarding overtraining, and she definitely was overtraining back then. So she won the javelin and 80 meter hurdles, she got gold medals in that, and the javelin on her very first throw, she tore cartilage in her shoulder. So when she runs the 80 meter hurdles, she and the second place competitor, they finish at the same time, and when they looked at the photo finish, they couldn't tell who had won. But when Babe crossed the line, she's throwing her hands up, and she's running around saying, "I won, I won!" and she's, you know, I guess today, we would kind of call it the the victory dance, you know, and, and when the judges looked at the results, there was four of them, two of them thought Babe had won, two of them thought the second place competitor, and after the language and the fact that she was in a row running around saying she won, that's when they gave it to her. And so that was, you know, very controversial. And then when she got to the high jump, she did, the, the way she did, it was an unconventional kind of way to jump over the high jump. And then when it was between her and the one other competitor, they told Babe, even though she'd been jumping the same way, the whole time, that you're, you're not jumping the right way. So you're gonna get the silver medal, and this other girl was going to win the gold medal. So you know, there was a lot of controversy there. And then the medal that they gave her, we've never seen this happen again, in Olympic history. It was kind of like half gold, half silver. And that was the medal they gave her and nobody has ever received another medal like that. So I don't know if it's like, well, we kind of know you won, but you kind of violated one of the rules of the way you jump and yeah, we should have told you after your first jump that you shouldn't have done that rather than towards the end of the competition. So maybe this was their way of, of trying to make amends on it. But she totally won that event, but still got second place.

Kelly Therese Pollock 24:01

So this is this remarkable athletic achievement, first at the AAU championship and then at the Olympics, and then she just stopped doing track and field. And, and that is not what she's largely remembered for, even though this is just it's incredible. So so what what happens here, what causes her to say, "Okay, I'm done with track and field now and I'm going to move on and you know, focus on other sports?"

Dr. Corye Beene 24:30

You know, she wanted to help her family out, they did not have a lot of money. And now you know, she understands, hey, I'm this huge star. When when she came back after the Olympics, she came back to Dallas, there's a parade thrown for her. And when she goes back to Beaumont, there's a parade thrown for her, people are talking about her. And I'm gonna go back to the Great Depression again because I think she is the right athlete and in the right time. The Great Depression, we know, devastated families. We had on average 25% unemployment rate. And you know, the early day, early years of the Depression, there is no welfare, there is no safety net for anybody. And it's a very bleak time. And I think that Americans were excited to have someone that they could rally around, especially at the Olympics, somebody who was kind of like the shining star in the darkness of the Depression, where, you know, you could you can cheer her on and leave your terrible, you know, economic woes behind. And I feel like that that is a big part of the story. But you know, she's trying to monetize her winning now. And she does. She plays in baseball exhibition games, she pitches in the major leagues. She played pool for money. She scrimmaged in football games. She got sponsorships, she, they even asked her to play, I mean to participate in vaudeville shows. And for all of the very young listeners out there who don't know what a vaudeville show is, it's like a stage show, she would get up there, she would play her harmonica, which she was famed, that's one of the things she was always known for. She got on this treadmill where she's running, and this other girl gets on another treadmill to try and beat her. So that was something they did on the vaudeville show. She's singing, she's playing the harmonica. And so she made money doing that, but she didn't like that, that wasn't who she was. She was an athlete, and she wanted to get back to competition. And after, after she finding ways to make money, she also has another basketball opportunity. So between 1933 and 34, she's playing 91 basketball games with her team called the Babe Didrikson All Americans. It was an all men team except for her. And she's making $1,000 a month doing that. And just to give the listeners a perspective, people who had jobs during that time in the Depression, they're making about $40 a month. So you know, if you if she's making quite a bit of money doing that. And then she starts playing baseball with this communal religious society called the House of David. And these guys were all men, they had really long hair, they had a beard, and they invited Babe to pitch for them. And she would come in on a donkey, they would all come in on their baseball games on a donkey. And she was like, "I don't know, if people are laughing at me, or with me, I'm not sure you know what's going on there." But you know, she was, she knew how to have a good time. And she she knew how to joke around. But she was paid $1,500 a month to pitch for them. And the guys were only paid $500 a month. So you know, she is just trying to do everything she can to make money. She to her credit, she sends the majority of the money home to her parents and her siblings. And she, to give you another perspective, again, on the money during the Depression, women, if you were female, a female garment worker say in a New York sweatshop, you made $2.39 a week, if you were a female, and were lucky enough to have a job in the depression. So I'm trying to give all the listeners a perspective on just how much money she is actually making.

Kelly Therese Pollock 29:01

Yeah, it's it's such a tension too because there's the she's making money any way that she can, you know, trying to try to put all these things together into something which isn't at all the way we think about professional athletes today who just sort of get paid to do do the sport; but at the same time, if she is making money, then she can't compete as an amateur and that's what most of the competitions are in at least some of the sports that she cared about. So can you talk too some about that that tension and what that does to you know, her competing interest in wanting to make money but also wanting to compete at the highest levels of these games?

Dr. Corye Beene 29:40

Right, so because she's making all this money in regards to her sports fame, she's not going to be able to be an amateur in golf. So, one of the things about Babe is she liked to how can I say this nicely, embellish the truth. She I would always stretch the details of what the truth really was. She, you know, she said that she saw Bobby Jones, the golf legend Bobby Jones play. And she said, "I want to play golf now." And you know, a lot of writers have said, "Well, she had never played golf before. She was introduced to the game, you know, in the 1930s." Well, that's not true. She did play golf, she learned how to play golf as a kid in Beaumont. But it makes the story better if she just randomly picks it up in her 20s, and has never done it before, doesn't know anything about it. But as golf is her next venture, she finds out that she can't be on the amateur circuit, because you can't violate the amateur status if you've already made money. So that's another reason she has to try and find all these other things to do to try and support herself. But you know, golf is what she is most known for. So she is going to play in, you know, in golf exhibition games, but they're not going to let her play on the amateur circuit until she, she has to be three years free and clear of making any money in regards to any other sports. So it's going to be a while before she gets to be on the amateur circuit, which she really wanted to do.

Kelly Therese Pollock 31:32

Yeah. And so it's around this time in her life, then that she meets George, who becomes her husband. It's so important for sort of the the direction of her career and what happens next that that she meets him and they get married. Can you talk some about the importance of that to what happens in her life, but also kind of about the relationship that they had?

Dr. Corye Beene 31:56

Right? So in 1938, she asked to participate in the Los Angeles Open, which was an all male golf tournament, and the promoters there to their credit, said, "Oh, Babe Didrikson, oh, yeah, we want her." So again, publicity stunt. And they pair her with George Zaharias, who was a professional wrestler, and they, you know, played together, and they hit it off, because by the end of that year, they were married. And he's just like her, he understands self promotion, he understands publicity. He, you know, as a wrestler, you understand that those things. And he takes it upon himself to be like her, her agent. And their relationship really has a lot to do with putting bait out there, and getting her to do this, and getting her involved in this, and pushing her in these golf tournaments. So, yeah, he, he was the right partner for her to continue to foster this. You know, she always said, "I am the greatest!" She said it way before Muhammad Ali, would ever say it. And George was totally on board with that.

Kelly Therese Pollock 33:18

Yeah, yeah, that's just, it's amazing to see, you know, we can talk about sort of the the gender dynamics and their relationship, but it's, it's really great to see, in some ways, a husband at that time, who's like, "Yes, my wife is going to be the famous one, and I'm going to support her and not just support her, but push her, promote her," You know, and that, that doesn't mean they had a you know, perfectly, like, feminist marriage or anything, but at the very least, he sort of saw saw that in her and was willing to support that,

Dr. Corye Beene 33:49

Even though he is the one that is booking all these things for her, he often did not travel with her. And that always hurt her. And, you know, she always wanted him to, to come with her when whenever she went anywhere. And so, you know, that kind of strained their relationship. But yeah, it was not a perfect relationship, that's for sure. But it maybe was a marriage ahead of the times in the fact that he knew that she was the star and he was okay with her being put up on the pedestal and him kind of being in the shadows.

Kelly Therese Pollock 34:29

So can we talk some too about over this time period between when she is this Olympic star to when she becomes this golfer? What changes there are in sort of her presentation of herself, you know, she's still braggadocious but, but the way she presents herself, especially her gender performance over that time, how that changes?

Dr. Corye Beene 34:56

Well, for listeners who know something about golf, you know, it tends to be a very polite game. I think it might be the one of the last sports left that there is an unwritten code of conduct that men and women must follow. Like, you know, it's not polite to cough or make noise when the golfer's on their backswing before they hit the ball. And it's not polite to walk in somebody's line. And you know, there there's no rules on, "Well, you can't cough on somebody's swing." It's unwritten, and back in Babe's day, for girls, it was a lady-like sport. It was a genteel women's sport. And the girls that played in these amateur tournaments against her, did not like her. These are the Country Club, well-to- do kind of women. And Babe was not, right. Babe is very rough around the edges, she's crass. She is somebody who speaks with no filter. And what else does she do is she doing? She is bragging that she's going to win. She would often come to a lot of these golf tournaments, and she would say, "Babe's here. Who's gonna come in second?" And we we just don't see that kind of behavior by any females in sports. And so it really alienated a lot of the girls on the tours. And even when I was talking about her track and field days, I mean, people would kind of silently cheer if she didn't win something, or if she didn't get the exact mark she wanted. And people were kind of always, "Darn it! She didn't do what she said she was going to do." So people, there were a lot of girls on the circuit rooting against her because of her attitude, and her impolite ways. And she was just, she was not about sticking within these strict gender norms that we see at the time. And maybe that's another thing that got her all of the attention it got her.

Kelly Therese Pollock 37:22

Yeah. Although she did sort of follow their pattern of you know, wearing skirts and sort of wearing lipstick and kind of ways that the the women golfers of the time were dressing.

Dr. Corye Beene 37:34

Yes, one of her friends said, "Hey, we need to doll you up a little bit, you know, we put some makeup on you. And we need to make sure your nails are done and that you're wearing, you know, the nice skirts and the nice outfits." And they did try to feminize her because the media was just terrible towards her. I mean, they they called her these these terrible names that today, if somebody called I mean, you know any female athlete, some of the things they called her, I mean, they would be fired because of the sexism and discrimination towards her. But she was, you know, it did hurt her when people would criticize her looks. And you know, one writer said, "She's not conventional conventionally pretty." I mean, if you call any girl, that I mean that that hurts you or whoever you are, I mean, even if you're, you know, some gorgeous supermodel, if somebody called you that, you wouldn't start to say, hey, well, it hurts you. So to try and combat combat that. That's why she tries to make herself look more traditionally feminine when she's playing golf.

Kelly Therese Pollock 38:55

So she is able to enter golf as an amateur, she sort of takes that time off that she has to take from making money at sports, and largely because George can support her. And then, and then she's able to go back into competition as an amateur. But then eventually she starts competing as a professional. So can you talk about that and the in the beginnings of the LPGA?

Dr. Corye Beene 39:19

Well, as she's competing professionally, it's her husband, George that says, "Hey, women need their own professional circuit, just like the men." And so she and several other women are the founding members of today what we would call the LPGA, in 1950, and they are able to largely because of Babe, or maybe I should say entirely because of Babe, the money in the purses for the competitions will increase. And she wins many tournaments. So she won as a pro 13 consecutive tournaments, and as an amateur, she had won 17 straight. That's the record still today. And in total, if we add up all the golf tournaments she ever participated in, she won 82 golf tournaments. And she, to her credit, she said, "Of everything I ever did, golf was always the hardest." And anybody who's played golf or who has attempted to play golf, can understand that. And for all of the the listeners out there who play golf, aren't y'all happy to hear her say that yes, it is the hardest sport that she ever had to tackle. Because it it can be infuriating at times, if you've ever played golf. So she starts, helps start the LPGA, and it it goes well for her. But sadly, within a few years, she gets colon cancer. And you would think that that would be the end of the story. But after she has surgery, they put a colostomy bag on her. And she still goes out and plays golf and wins a couple of more tournaments. Now, a colostomy bag is where you're, when you go to the bathroom, everything goes into the bag. And I can't imagine having to that attached to you and trying to play golf and swinging. And I just think that that is just who she was. She was an overcomer. And no matter what she did, even if she felt like you know the cards were stacked against her, this was a great example of, "Okay, yeah, I've just had cancer. Yeah, I was in the hospital for a while. Yeah, I've got a colostomy bag on me. But I'm gonna keep going, I'm gonna, I'm gonna keep persevering. And because I know I can do it." And she did for a while. And then, sadly, her cancer came back. And she passes away at the age of 45 in 1956. But, you know, she has all of these accomplishments. And I hope towards the end of our conversation, I can list everything that all of her accomplishments.

Yeah, yeah. Before we get to that, though, I'd love to talk some about her friendship with Betty Dodd, who, you know, is left out of some of the sort of stories of her life and, you know, is sort of sidelined in a lot of that. But Betty Dodd is hugely important to her in the last few years of her life, including after the first surgery. So can you can you talk some about that that friendship, possibly something more than friendship that they had?

So Betty Dodd was 19 when she met Babe, and Betty was on the pro circuit with her. So Babe was 39, Betty was 19. And they developed a very close relationship. She traveled with Babe and George, even moved into the house with them, for six years of her life, and there seems to be a an intimate relationship between the two of them, depending on who you read. But I think if you move in with someone, then that to me means it was probably, you know, a romantic relationship. But it's Betty that is there the whole time helping her through cancer, being in the hospital with her. Her and George were with Babe when Babe passes away. And that probably is another reason that maybe Babe has not gotten the attention that she deserves. When when you start going into aspects of people's personal lives, you know, unfortunately, it shouldn't but it does cloud your accomplishments. And especially in the 40s and 50s, you know, very taboo topic. That is probably something else that maybe alienated a lot of other people.

Kelly Therese Pollock 44:24

Yeah. So I think then the the last thing I wanted to ask about is after Babe gets cancer, the the last few years of her life when she even when she's sort of winning tournaments and stuff, she becomes this ambassador for raising money and awareness of cancer, which is a totally different side of her personality, which up until then had been sort of completely about her and about winning, but suddenly is philanthropic and humanistic. So can you talk a little bit about that and that sort of change in her?

Dr. Corye Beene 44:56

Well, unlike today where cancer and cancer research is discussed by everyone, it's not something that to be embarrassed about, during Babe's time, people did not talk about cancer, and they would not many people wouldn't even seek treatment for it. They wouldn't, they just wouldn't want to talk about it. So Babe is really that first person that brings all of this to the forefront. She is very transparent in her struggles. You know, she told the media, "I have colon cancer. I'm going to have to have surgery." She would even let reporters in when she was in her hospital bed, to come talk to her and interview her. So, to her credit, she is bringing cancer awareness to the American public. She and Betty would often go visit other sick children in the cancer ward and cheer them up. Betty would sing. Babe would play the harmonica. She would bring awareness to the topic. She started fundraising for cancer research and money towards looking into how to treat cancer. So she kind of you know, to me, that's just as important as her athletic accomplishments. And with her, that's when people started saying, "Oh, okay, well, let's, let's, let's talk about this. Let's, let's figure this out. Let's have more treatment." So you know, she opens the discussion. And we know that it's such an important discussion.

Kelly Therese Pollock 46:45

Yeah. So is there anything else then that you want to make sure we talked about?

Dr. Corye Beene 46:49

Well, I just want to list all of her accomplishments if I can.

Kelly Therese Pollock 46:54

Yes, please.

Dr. Corye Beene 46:55

Because there's a lot. So if you'll give me some time here, I'm gonna I'm gonna list everything. So in 1999, at as we're turning into the 20th century, ESPN made a list of their greatest athletes of that century. Babe was 10th on the list. The Associated Press called her the ninth greatest athlete. Sports Illustrated called her the second greatest female athlete of all time, right behind Jackie Joyner Kersee, who has six medals in four different Olympic Games. She started the LPGA and she is in the LPGA Hall of Fame. She's in the National Women's Hall of Fame. She had Olympic or world records in five track and field events. She still holds the record for the baseball throw, which is not an Olympic event anymore, but it's 272 inches. She won 82 tournaments. She was the Associated Press Woman of the Year six times. She was a three time AAU All American basketball player. She won various events in speed skating, cycling, squash, shooting, billiards. So I'm here to make the case Kelly, and I hope your listeners join me that she is the greatest athlete of all time, male or female. No offense to all the other great athletes out there. I know people always say, "Well, Michael Jordan is the greatest athlete or Bo Jackson is the greatest athlete." But with all due respect to them, I don't think any of them come close to what Babe was able to accomplish. And so I feel that we should say she is the greatest athlete, American athlete of all time up to this point. But I find it sad that she might have been one of these athletes who could have gone to another Olympic game, but as many of the viewers listening notice, you know, we didn't have an Olympics in 1940 and 44 because of World War II. So you know, she because of that she didn't have another chance to keep going in track and field and who knows what she could have done. So will you support me in that, Kelly? Can we say she's the greatest athlete ever?

Kelly Therese Pollock 49:40

I support you. Excellent. Yes, I support you. Alright, so if listeners want to learn more about sports and sports history, how can they subscribe to your newsletter?

Dr. Corye Beene 49:49

My link is if you go to awesomesports.substack.com, my sports letter is free and it's a bi- weekly newsletter, and I play up the great things about sports in the United States. So, you know, I like to talk about history that's been made in different sports. I love to talk about sports history. And I love to talk about inspirational sports stories. So all the good stuff, so I hope the listeners would love to subscribe.

Kelly Therese Pollock 50:27

Yeah, I will put a link in the show notes too, so people can find it. So, Corye, thank you so much for speaking with me. And thank you for introducing me to this amazing woman.

Dr. Corye Beene 50:38

Thank you for having me, Kelly.

Teddy 50:43

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. You can find the sources used for this episode @UnsungHistorypodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on Twitter, or Instagram @unsung__history, or on Facebook @UnsungHistorypodcast. To contact us with questions or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistorypodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate and review and tell your friends.

Corye Perez Beene

I am a United States History Professor and certified “sports nut.” I find the sports stories from the past to the present that celebrate the Awesomeness of American Sports.