An American History of Coffee

Americans love their coffee; according to the Fall 2025 National Coffee Data Trends Report, 66% of adult Americans drink coffee every day, averaging three cups per day. This devotion to the caffeinated beverage is nothing new. Even before Bostonians dumped over 90,000 pounds of tea in the harbor, Americans were sipping cups of joe. George and Martha Washington served tea at the President’s House in New York, and after he stepped down as president, George Washington even tried growing coffee trees at Mount Vernon. Joining me in this episode is Dr. Michelle Craig McDonald, Director of the Library & Museum at the American Philosophical Society, and author of Coffee Nation: How One Commodity Transformed the Early United States.

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The mid-episode music is “Coffee in the Morning and Kisses in the Night,” by Gus Arnheim, 1934, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

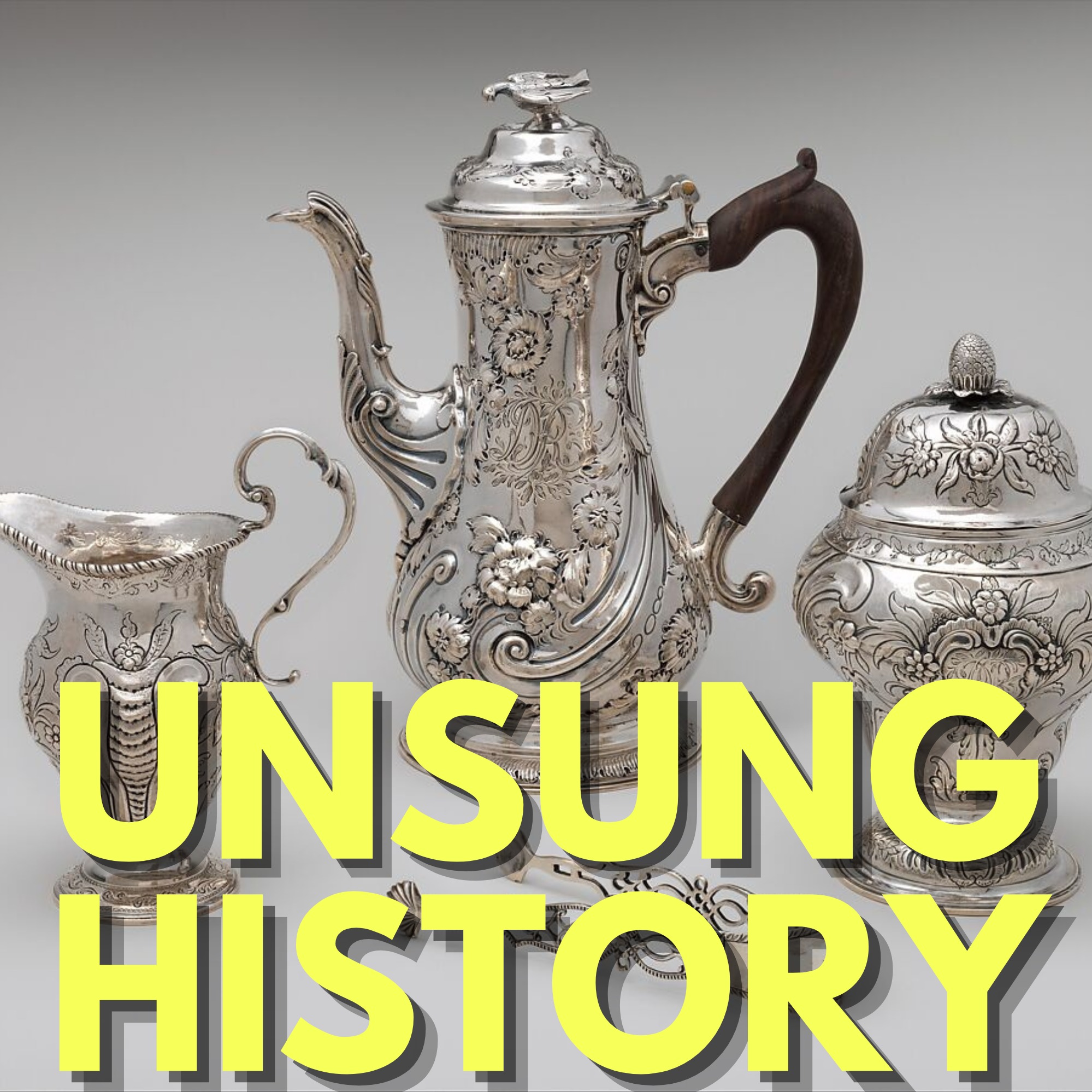

The episode image is of a coffee pot, made by Robert and William Peaston and accompanying sugar bowl, creampot, and tongs, made by Myer Myers; the items were owned by Dorothy Remsen, who married Abraham Brinckerhoff of New York in 1772. The coffee set is on view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 704; and the image is available as part of the Met's Open Access policy.

Additional Sources:

- “Coffee’s Creation Myth: How Coffee Conquered the World,” by Blake Stilwell, Coffee or Die Magazine, April 16, 2022.

- “The Boston Tea Party at 250: History steeped in myth,” by Gabrielle Emanuel, WBUR, December 14, 2024.

- “Coffee and the White House,” by Tianna Mobley, The White House Historical Association, May 2, 2022.

- “Coffee,” George Washington’s Mount Vernon.

- “Coffee: World Markets and Trade,” by United States Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service, December 2024.

- “Poll reveals America’s coffee consumption habits,” by Georgia Smith, Global Coffee Report, September 11, 2025.

Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brands

Kelly Therese Pollock 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app so you never miss an episode, and please tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers, to listen too. As legend would have it, sometime in perhaps the ninth century, an Ethiopian goat herder named Kaldi found his missing goats dancing all night after eating the berries of a small tree. Kaldi himself tried the berries and felt a rush of energy. He then introduced these berries to nearby monks, who threw them into the fire, fearing them the work of the devil. The smell of the roasting berries, though, was so enticing that they pulled them out to make the world's first coffee. Whether Kaldi and the goats had anything to do with it, coffee did originate in Ethiopia and was being traded throughout Africa and the Middle East by the 15th century. By the 18th century, European demand for coffee was so great that the Dutch and the British were both experimenting with growing coffee trees in their American colonies. An attempt by the governor of Barbados to make the island a hub of coffee production failed, in part because Barbados was so dominated by sugar plantations, but even more, because Barbados didn't have the elevation needed to grow coffee trees. That mountainous terrain was found instead on another British colony, Jamaica, where the former governor, Sir Nicholas Lawes, planted the island's first coffee trees. At Lawes' urging, the British House of Commons passed, in 1732, an act for encouraging the growth of coffee in His Majesty's plantations in America, which reduced the import duties on coffee grown in the British colonies, as opposed to foreign coffee. Several of the islands ceded to the British by the French in the 1763 Treaty of Paris were likewise well suited for growing coffee. From Jamaica and the rest of the British West Indies, coffee headed to British North America. By the early 1770s, at least a third of the coffee imported into British North America, and sometimes as much as half, came through Philadelphia. That trade grew quickly, more than doubling between 1768 and 1773, when 288,632 pounds of coffee was imported from Jamaica to Philadelphia. Some North Americans sourced coffee from elsewhere in the world, but the favorable taxes for coffee from the British colonies made other coffee significantly more expensive by comparison. Through the mid 18th century, most North Americans were using imported coffee pots, which at 25 to 40 ounces were significantly larger than teapots. The coffee itself was brewed in a kettle and then transferred to the coffee pot, which was tall and thin with the spout near the top, so as to avoid pouring out the grounds. Coffee pots were made from a range of materials, from porcelain and ceramic to metals, including silver for the wealthiest coffee drinkers. Paul Revere, best known for his midnight ride, was a Boston silversmith who made a dozen coffee pots in the decade and a half before the American Revolution, including one as a part of a wedding set for William Paine, that took 45 ounces of sterling silver to create. After the December, 1773 Tea Party, when Bostonians destroyed over 90,000 pounds of tea worth over 1.5 million in today's dollars, the British Parliament passed four acts that they called the Coercive Acts, but which the American colonists referred to as the Intolerable Acts. In reaction to these acts, which limited the autonomy of British North American colonies, especially Massachusetts, the Continental Congress formed, and it banned the importation of British tea, and then expanded to an embargo on all goods from Britain, Ireland and the British West Indies, which of course, included coffee. Americans never stopped drinking coffee, but it became harder to come by during the war, with one source of it being the capture of ships sailing under British flags. Some of the colonies set the price of coffee, along with other goods during the war. Since coffee could be stored for long periods of time, unlike many other foods, retailers would store their coffee to wait for a favorable pricing situation. After Congress signed the Treaty of Amity and Commerce with France, In 1778, the French West Indies opened to American trading. And by 1781, 93% of coffee imported into the United States came from the French Caribbean. Accordingly, coffee prices returned to pre revolutionary levels. In the next half century, though, Americans would find a new source of coffee. In the 1830s, the US Congress repealed the tariff on foreign coffee, since there were no sources of coffee in the continental US. At the same time, Brazil began to invest in coffee production, leading the world by 1843. A year later, Brazilian coffee made up over 60% of US coffee imports. As of December, 2024, Brazil remained the top supplier of coffee to the United States, with 32% of American coffee being imported from Brazil. According to the Fall, 2025 National Coffee Data Trends Report, 66% of adult Americans drink coffee every day, averaging three cups a day. As Bill Murray, CEO and President of the National Coffee Association noted, "Coffee's staying power as a beloved touchstone in Americans' daily lives is remarkable, and its contributions to our health and our economy give Americans even more grounds for celebration this National Coffee Day and every day." Joining me in this episode is Dr. Michelle Craig McDonald, Director of the Library and Museum at the American Philosophical Society, and author of, "Coffee Nation: How One Commodity Transformed the Early United States."

Music 9:22

Hi, Michelle. Thanks so much for joining me today.

Dr. Michelle Craig McDonald 9:53

Thank you for having me on the show. I appreciate it.

Kelly Therese Pollock 9:56

I am a little bit obsessed with coffee. Have been addicted for many, many decades now. So it was really exciting to read about some about the history of coffee. I'm wondering what got you interested initially in doing this research?

Dr. Michelle Craig McDonald 10:12

Well, in addition to my own desperate love of the drink, it was, I will say it was a, it was a topic that I came upon almost by accident, when I started graduate school. So this was a number of years ago. For the listeners who can't see me, I now have white hair. But it was the confluence of two classes. So I took a class in early modern British history, and I was at that time I thought I had applied to graduate school to say I was going to study the emergence of public education after the Civil War in the United States. That is clearly not what I chose to study. But I was still really interested in ideas about literacy. And so I thought I would look at places where people could get their information if they couldn't read or write. And so I was focusing on inns and taverns, and especially coffee houses, where news and events were frequently discussed out loud, discussed in groups. And so that was the first thing that sort of caught my eye in the coffee realm. The next semester, I took a class on Atlantic world history, which looks at how the Americas and Africa and Europe are tied together. And I thought, well, I can't look at coffee houses again, but I can look at coffee plantations and see what I could learn about how coffee was grown and how it was distributed. And what I realized in these two classes is that there was one really interesting set of books that were looking at the history of coffee houses, mostly in Western Europe, but for them, the coffee just sort of showed up, ready to be consumed. And then in books about coffee plantations, and they were far fewer, really, for the 18th century, most of the focus was on sugar. But where I could find references to coffee, they end pretty much at the port of the island or the colony ready to be exported. But these books weren't talking to each other. And so that's where the idea for this project came about, a history that looked at how and when coffee came to the Americas, how it was grown, how it was traded, and ultimately, how it was consumed, how it was drunk by the people who came to love it.

Kelly Therese Pollock 12:16

And what are some of the sources that you're able to look at? I assume if you go into like a newspapers.com and type coffee, you're going to get way too many results to be useful. So how did you go about figuring out what what to look at?

Dr. Michelle Craig McDonald 12:29

Advertisements are helpful. But you're right. You have to have parameters, because there's a lot of them, especially as we get closer to the 19th century. But I used a range of sources. I lived in Jamaica for about a year and a half to do research there. And so in that place, I was looking at plantation records. I was looking at wills and probate inventories to get a sense and maps, to get a sense of where coffee plantations were located and what kinds of people owned them, what sorts of labor was used to grow coffee. And then when I moved into the trading section, I'm spending a lot more time with customs papers and with naval office shipping lists and with merchants account books to get a sense of when coffee is shipped and where coffee is shipped and in what quantities. And then for the consumer side of the story, I spend a fair bit of time, definitely with advertisements, but also in letters and diaries, because it's one thing to know that people are drinking coffee, but that's not the same as knowing why they're drinking coffee. So I was interested in all of those questions, and then finally, I would be remiss if I didn't add that I had a before I became a historian, I had a career for about eight years in museums as a curator and educator. And for me, material culture is still really powerful as a resource base. And so I spent a lot of time looking at coffee pots and coffee cups and coffee grinders, coffee spoons, everything that's related to how you prepare coffee, and how you serve coffee. So all of those are the kinds of research resources I was interested in.

Kelly Therese Pollock 14:07

I think one of my favorite tidbits in the book was that the first coffee grinder to come to what's now the US was on the Mayflower.

Dr. Michelle Craig McDonald 14:15

Yeah, yeah. I was trying to find as many touchstones as I can. And when I found that mortar and pestle for grinding coffee. And it's not surprising, actually, because many of these religious refugees were coming through Amsterdam, and Holland actually became very interested. The Dutch became very interested in coffee trading in the 17th century. So I shouldn't have been surprised, but I thought, the more I can link it to the Mayflower or to Jamestown, there's another reference to those who are living in Jamestown as well, the better I can try to position this in a narrative that people think they already know.

Kelly Therese Pollock 14:45

Let's talk a little bit about the way that coffee is grown, and it's so striking that you're focused on the Americas, on especially what becomes the US, and within the whole British Colonies of North America, you cannot grow coffee. How? How is coffee grown? How is it different than the way sugar, for instance, which is also often a tropical product, is is grown, is maintained?

Dr. Michelle Craig McDonald 15:13

So there are some similarities and there's some differences. Those are two commodities that they do grow up, you know, adjacent to each other. But there are some important distinctions too, and the first one is timing. So sugar comes over to the Caribbean through British imperial channels, but also through French and Dutch and Spanish. All European empires are interested in sugar, but it comes over earlier in the 17th century, and it is a fantastically profitable industry, and that's one of the reasons why it's gotten, I think, so much attention from historians, as opposed to other commodities that were grown in the West Indies. But it favors low lying regions, so coastal regions, for the most part, in Caribbean colonies. And it needs a lot of sun, it needs a lot of rain, and it processes, it requires being processed very quickly. Once sugar cane is cut, you have a you've opened a time window in which it needs to be processed or it will begin to ferment. And once that happens, you can't use it to produce raw or refined sugar. So that's a 17th Century story. It has huge implications for the Caribbean and the peopling of the Caribbean, because sugar is grown pretty much exclusively by enslaved labor. It is the genesis of the transatlantic slave trade that repopulates the West Indies and the legacies of which you can still see today. So that is, is a story that I think has been beautifully captured by many really strong histories. Coffee is similar in the sense that it is reliant on enslaved labor as well. But it comes later. It arrives in the early 18th century, in the 1720s, and it requires very different circumstances for growing. So coffee grows best at above 2000 feet above sea level, even better still, 4000 feet above sea level. And so there you're looking at places in the Caribbean that have mountain ranges. And there are a lot, because these are many of these are legacies of volcanic islands. So places like Jamaica or San Domain, which is now Haiti, or the Dominican Republic, which at that point was Santo Domingo, a Spanish colony, Cuba, many of the Eastern the smaller Antilles, those have mountainous elevations where coffee grows well, but you're not going to see it in other places. So coffee in the Bahamas right out. Coffee in Barbados, not a good bet, because it doesn't have the right climate. It doesn't have the right growing conditions for coffee to thrive. But I will say that what these two commodities have in common is very much a reliance on enslaved labor to make them work. But the scale, sugar plantation is usually very large. Coffee farms traditionally much, much smaller, but both dependent on chattel bondage.

Kelly Therese Pollock 17:56

There has been a lot, of course, in the news recently about tariffs in general, and tariffs and how they are affecting coffee and coffee prices. But one thing that's really interesting about what you're writing about is the way that tariff and price protections have been so important to really the whole history of coffee in the Americas. Could you talk a little bit about that, and the ways, that sort of unexpected ways that we see that really affecting how coffee as an industry progresses?

Dr. Michelle Craig McDonald 18:28

I'm gonna, I'm gonna make you wait for Brazil, even though I know that that has the closest resonance with today's conversation. But I will bring it up. Let me give you three touchstones to think about with coffee and pricing. So the first is going to be how coffee first became an important British imperial project. So because there were other empires that were competing, and because it was not undertaken, for the most part, by planters with the same level of means as sugar planters, early on, it needed protection if it was going to grow. So one of the characters I introduce in the book is Sir Nicholas Lawes, who was a governor in Jamaica. And when he retired, he becomes interested in different botanical experiments, and coffee is one of them. He planted the first 28 trees, in coffee trees in Jamaica. And when he passed away, or soon after he passed away, a number of planters got together and petitioned parliament for basically tax protection. What they wanted was which they received. Parliament agreed. What they wanted was that for coffee that was grown and sold within the British Empire to be tax free, and for a heavy import tax to be placed on any coffee that came in from a colony other than the British Empire. And they succeeded, and that's part of what gave them the financial buffer to be able to grow the industry as well as they did. The second moment I'm going to give you, I'm going to fast forward. So we're so used to thinking about the American Revolution as fighting against, and it was, I'm not going to say it wasn't, but fighting against efforts by Parliament to control economic activity in what becomes the United States. So it's sometimes surprising when I tell people that during the Revolutionary War, because of scarcity and increasing price inflation as a result, it's not surprising that during war, prices would go up. There's disruptions in trade, there's efforts by both the British and the American army to secure supplies, and so there's fewer and fewer goods to buy. Prices are naturally going to go up as supply goes down, but there were a number of goods that the Americans by then states, felt were necessary for everyday life, and so they initially began, started in New England, in Massachusetts, in New Hampshire, Rhode Island, but then trickles down to New York and also Pennsylvania, almost all colonies enact various forms of price structures or limits. And they identify about 25 or 26 goods so they think are essential to daily life. coffee is among those. So to me, that's a really important piece of evidence, because it demonstrates that coffee has become so common. Tea was not on that list. Coffee has become so common that it is an expected part of daily life, and so as a result, like flour and corn and peas and beets, it's going to be protected with a price cap, so that people can't start charging higher and higher rates. And the third example, which does bring us up to today's thoughts on coffee and tariffs, is closer to the end of my book. So most of my book focuses on North American, West Indian commerce, but my last chapter, I had to take a turn, because by the 1830s, Brazil had really begun to emerge as this leading powerhouse in coffee production. And in 1832, I think it became effective in 33, there's a group that have joined together to petition Congress to abolish all taxes and tariffs on imported coffee and they're doing it for two reasons. First, the coffee importers are seriously interested because this will give them a global advantage. But they're joined, interestingly enough, by temperance movement, who are trying to find an alternative to alcohol that is a beverage that can be broadly embraced, right and promoted. So these two groups come together and successfully petition for the United States to become the only nation in the world that did not tax coffee, and it was that combination of US importation and increasing Brazilian production that created, candidly, a partnership that persists to this day.

Kelly Therese Pollock 22:47

Yeah, it's a it's a fascinating history, and I think you know what you just said about the temperance movement, I mean, it's really interesting to think about how little moralizing there is about coffee compared to alcohol, when they're both highly addictive, they're both, as you mentioned, reliant on enslaved labor. And you know, in this case, it's a product that does not even grow within the continental US. Was it just that they're looking for sort of non alcohol sources? Is it just the losing battle to try to fight against coffee? Like, what's your sense of what was going on there?

Dr. Michelle Craig McDonald 23:25

Well, there is some pushback. First of all, let's talk about addiction. There's fairly early on, I mean, by by the late 16th, even 17th century in Europe, there's a recognition that coffee has an impact on the body. Mind you, some of the accounts from that early are amusing in terms of what they think how coffee impacts the body. And there's various kinds of medical literature. Some of those who support coffee as consumption are saying it's, you know, great for everything from typhoid to flatulence. I'm not joking. But then there's a whole other range of pamphlets and writers who are arguing that coffee causes infertility, that coffee causes impotence. And there's even a recognition that, because it's an imported good in Western Europe and then certainly in North America, that coffee causes dependence. It becomes associated with this word dependence, really early on. So you have, you definitely have practitioners who are, who are not necessarily always fans of coffee as early as that, but even in in North America, in the United States, that reappears. Cookbooks don't become regularly published in North America until the 19th century. There are some late 18th century examples, but for the most part, they've been using imported books that were coming from England primarily. But even there, you have people who are beginning to distinguish between coffee, coffee brewed for children, coffee brewed for people who are ill, coffee brewed for the elderly, because there's a recognition that caffeine can have a different impact depending on who you are and what your health is like. But I wanted to return to one other aspect of that, which is this question about, about the association of coffee with with slavery. Because it it is. There's a wonderful, if I had more time, and it might be another project, I published one article about it, but it could use a book. Their coffee does become not quite as prominently as sugar, but certainly with sugar, one of the primary targets of the pre produce movement of the early 19th century. So it's an arm of the abolition movement, and they're looking for ways that you can try to find coffee that's not produced by enslaved hands. Now it's easier for something like tea, which is produced in China or India, not by what I would call free labor, but not by enslaved labor. Coffee is more challenging. It's not until after the Haitian Revolution and Haiti gains independence for the French empire, that you really have a large potential producer of free coffee. The challenge there is that the United States, like most of Western Europe, chooses to boycott Haiti because it is the first Black Republic, and so that does not become a viable alternative. But you will find them trying to promote things like chicory or everything is I mean, there really are efforts to try to grow coffee in North America to lessen our dependence and have a free a free labor option, but they're trying to burn rye and wheat and and and create a com as one as one abolitionist pamphlet says, they give all of these various options. You can try burning rye, you can try roasting wheat. None of these are very good,is how it concludes, because none of them really are coffee.

Kelly Therese Pollock 26:42

No, nothing is like coffee. You mentioned the material aspect culture. I wonder if you could talk some about that. And I mean coffee, of course, is striking, because people of all social classes eventually drink it and drink it in huge numbers, but the way they're preparing it, the way they're consuming it, the thinking around coffee and the rituals that go with it can be very different.

Dr. Michelle Craig McDonald 27:08

Can and that that is what I hope is one of the big takeaways from the book. My argument is that, because coffee is less expensive per pound than tea throughout the colonial period, or than chocolate, for that matter significantly less, many, many more people drank coffee than drank those other beverages. But how they drank it varied significantly. At the top end of the scale, I was looking at a range of different materials and price points. At the top of the scale, you have something like sterling silver, which is extremely expensive, right? A very small percentage of North America's population could afford a sterling silver set. And I but I will point out, and I do in the book, that if you were going to have a full sterling set, you would have a coffee pot, a teapot, a creamer, a sugar, sugar tongs, a tray. There's a wide range of accompaniments that can come with it. It's an expensive investment, but bearing in mind that a coffee pot is usually about twice the size of a teapot, the coffee pot will always be the most expensive object in that set, because it just takes that much more metal to create, right? But there were other options after plating became very commonplace. Metal plating, you could have silver plated coffee and tea services, and candidly, by the end of the 18th century, you wouldn't be able to tell the difference once they come across a process called Sheffield plating that bonds silver with other metals to a base metal, you can not only coat the outside, but the exterior, the underneath, really only if you picked it up and you knew the weight difference, would you know that you're not holding sterling in your hands. But coffee pots also come in imported ceramics, in stonewares, in painted tinware, really, any price point along the line, you can find coffee equipage that's going to match it. So I will also add there are these moments in the archive. You probably get this from from other speakers. There are these moments in the archive when you find something you think that's going to make an amazing story. The letters of Mary Shippen are one of those for me. She was married to Joseph Shippen. The Shippen family is very prominent in Philadelphia, very, very doctors, lawyers, very well off. But she's visiting a family, a relative, in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and she writes back to her husband Joseph, that for the most part, she's found the visit to be lovely, but she did notice that her hostess, when she is setting out afternoon coffee and doesn't have enough cups for everyone in the room, will add tea cups so that everybody has a vessel, right? And she's she's a little appalled by it, and she reminds her that her own coffee service set is chipped, and she implores Joseph to buy replacements. And the reason I love this story so much is it tells me a couple things. It tells me that there are families who are already invested enough in coffee and coffee consumption that they need and want a full set. And they recognize the difference when they don't have it. But it also tells me that people in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, her family, are just making do. They all serve coffee with what they have. So it's not required that you have all the equipage, but if you have the means and you feel like you have the social standing that that kind of etiquette is expected, it has become important.

Kelly Therese Pollock 30:20

And of course, that's all the same today. People drink coffee at all sorts of different price points with all sorts of different equipment. And so I want to go back to talking about coffee houses where we began. You know, I think that certainly many of us know how important and ubiquitous coffee shops are now. I've worked in several myself when I was in grad school, but I think what what we think of as the coffee shop now, while it may have connections to the the coffee houses that you're talking about in the pre revolutionary and revolutionary time, they are not exactly the same kind of place. So could you describe what that was like? The importance of those places, not just as a place to get and drink coffee, but as a an actual social space.

Dr. Michelle Craig McDonald 31:07

And that's a question that I grappled with a lot when I was writing this book. What is the distinction? What is the difference between an inn, a tavern, and a coffee house? And again, it was this really lovely letter that was written by an uncle to his nephew when he first moved to Philadelphia in the 1760s and he, I'm paraphrasing slightly, but he says, "Don't trifle your time away at the tavern. Don't trifle your time away at games of chance. If you want to be taken seriously as a man of business, get yourself to a coffee house." And there was a reason why. When you called yourself a coffee house, you were conveying something to the public about what you were and the kinds of activities you supported. All of these places serve food and beverage, and please don't misunderstand. Coffee houses didn't just serve coffee. That's that's not how they were like today's coffee houses. They had a full range of beverages, usually including alcohol. I only found one coffee house that didn't have the liquor license. It closed in two years. They had a full menu of food. Sometimes they offered accommodation as well, in the same way that inns and taverns did. But the ways that they were different is that coffee houses, and they call themselves a coffee house, because they were associating themselves as a place of business. They housed many of the activities that ultimately would become different industries, but weren't in the 18th century, in the in a colonial period. So coffee houses are places where currency exchange was compared. They would have regular exchange days. So currency from around not only the Empire, but around multiple empires, right? These are places of trade where merchants and traders are meeting, would be posted so that you would know, you know, with their relative value. They were places of information gathering. They kept business directories. They kept newspaper subscriptions. One coffee house is advertising that they spend over 400 pounds a year on newspaper subscriptions so that their members can be aware of what's happening around the world, where there's political unrest, where there might be environmental events or hurricanes, what's in fashion, right? These are all things they need to know. They served as places of maritime insurance. There wasn't a separate insurance industry. So if you wanted to get insurance for your ship, usually you were brokering it at a coffee house. So by setting themselves up this way, by calling themselves by that moniker, they were basically saying we are places of business, and that is our primary set of activities.

Kelly Therese Pollock 33:33

We've mentioned that coffee is not something that is grown within what becomes the US, but you do demonstrate that there are coffee brands that are US brands that start to really deliberately sell themselves as all American. That's a big part of their advertising. Can you talk some about that? What it is that they're trying to do there, and how they're succeeding in that with a product that, of course, has grown somewhere else.

Dr. Michelle Craig McDonald 33:59

The interesting thing is, so if I was going to take coffee, where coffee production, and put it into three big chapters, these would be they. In the colonial period, for the most part, when North Americans are drinking coffee, they're drinking coffee from the British Empire, primarily from Jamaica, or after the Seven Years War, when Britain gets the ceded islands from France, from places like Dominica or Grenada or St Vincent, right? But if you had coffee from somewhere else, you were sure to advertise it, particularly if you had coffee from the East Indies, from places like Java or Bourbonor from French San Domain. So there you do get to see a moniker associated in advertising with coffee. Normally, in an ad from this 18th century, coffee is literally just coffee, one of 60 goods that a shopkeeper is listing. But if they had French coffee, or if they had Java coffee, they would make sure to tell you, because that price was going to be higher. In the post revolutionary period, I'm going to get to your American branding in a moment, I promise. In the post revolutionary period, when the United States is no longer a part of the British Empire, they're looking around for different partners. And so then again, naming is important, because if you're importing coffee from Cuba or from or from San Domain before the Haitian Revolution, or from Puerto Rico, you're going to actually advertise where it comes from, because, again, people have already begun to distinguish differences in taste and sophistication in terms of brewing technique or roasting techniques from these different places. But by the 19th century, and again, particularly after the 1830s and the United States' very close affiliation with Brazil, almost all of our coffee, well over 90% of our coffee, is coming from that one supplier. But what you see in the advertising is a really interesting shift. Rather than focusing on Brazilian coffee, coffee itself becomes remade as an American product for two reasons, I would argue. Number one, we're not just importing coffee for ourselves, right? For the United States, we're importing coffee to re export around the world. So we're taking a Brazilian commodity and we're remaking it into an American export. To do that, right? You need to have faith in the American companies that are importing it, packaging it and selling it to you. So in that repackaging, it's very important for these merchants to emphasize their United States origins, but then by extension, that same overlay spills out onto the domestic coffee scene as well. Coffee becomes literally promoted as this all American beverage, and you see that in the advertising language, you see that in the advertising imagery, this affiliation of coffee, with with past presidents, with eagles, with other sites of nationalism, other signs of nationalism. And it's a very deliberate effort, and it's repeated in company after company after company, so that rather than saying we are proudly selling you Brazilian coffee, it is we are proudly selling you American coffee. Even though there was one, there's one beautiful coffee box I found, tin box I found that says United States coffee from its own provinces, Hawaii, Puerto Rico and Guam. and I thought at the moment, at first I saw it, I thought to myself, "That's because you couldn't grow coffee in the United States until you redefine what the United States was, and then you could claim that we had a domestic source of coffee," but it could never compete with something like Brazil.

Kelly Therese Pollock 37:37

I know that public history is really important to you. I wonder if you could talk about the the different forms that takes. And you know, do you, do you find that studying things like coffee helps with the ability to sort of connect with the public?

Dr. Michelle Craig McDonald 37:53

Absolutely, so public history for me, I should say so I mentioned I have a museum background. I've also spent a lot of time doing works with teacher education programs, with school groups, and all of that informs my current job. I now direct a library and museum, which is fantastic way of combining my past professional lives into one nice package. But to me, the distinction between public history and academic history, not as stark as it used to be, thank goodness, is about your audience and then your media. So academic history is your more traditional thinking about publications for K 12 teaching, or for college teaching or for other historians, whereas public history has, as its name implies, a mandate to think about as broad a reach as possible. To do that, I think it's especially helpful to start with a question that many people would find engaging, right? If I started with the question, you know, how does the United States restructure its trade networks in the early 19th century? That's not going to grab people as much as say, what is the history of coffee trading? Where does your coffee come from? How does that differ than where it came from in the past? That's a much more engaging interest point, I think, for a general public, about what is, in fact, a very complicated story.

Kelly Therese Pollock 39:11

I would like to encourage listeners to read your book and learn about that history of coffee. Can you tell them how they can do that?

Dr. Michelle Craig McDonald 39:19

Absolutely. The title of the book is, "Coffee Nation: How One Commodity Transformed the Early United States." And it was published by the University of Pennsylvania. So you can find it on their website, but you can also find it on Amazon, on Barnes and Noble, on many other any website that would sell books, that book appears. So I hope you do think about it. If you love coffee, or if you know somebody else who loves coffee, I'd like to think that it would make an excellent gift as we move through the holiday season.

Kelly Therese Pollock 39:46

I think everyone must know at least one person that loves coffee. Is there anything else you wanted to make sure we talked about?

Dr. Michelle Craig McDonald 39:53

The other reason I really like this topic, and I particularly like it as we're coming up to 2026, which is the 250th of course of the Declaration of Independence. And if you didn't know that by now, congratulations, next year is the 250th. It comes in a really nice time to think about some of our rethink, some of our American myths. So when people think about the American Revolution and these iconic stories, one that almost immediately comes to mind is the Boston Tea Party. And I'm not going to say that I don't like Boston, that I dislike the Tea Party. I'm just going to say I'm from Philadelphia, and Boston and Philadelphia, have a big rivalry when it comes to the 250th, but that's not why I'm making this argument. The Boston Tea Party is cast as this moment of American bravery, right, of this underdog going against the machinery of empire, breaking onto ships at night and destroying what had become a really hated commodity that represented parliamentary control. I start my book very deliberately and this was another aha moment in the archives very deliberately, with a story that I found in the letters from Abigail Adams to her husband John Adams. She was living in Boston at the time when he was in Philadelphia for the Continental Congress. And the story she recounted was of women lining up outside a warehouse owned by a man named Thomas Boylston, and demanding that he open it, because they knew he was keeping coffee. And this is when price controls had gone into effect. So he had removed his coffee, which stores for a very long time off of the market, so they didn't have to sell it at these deflated prices. But then they couldn't find any coffee at all to buy, and so they lined up. They demanded his keys. They went into his warehouse, they took the coffee out, and then they gave it to the city to sell it at the regulated prices. They didn't destroy it. They didn't steal it. They kept it and they distributed it for people to purchase at fair rates. And to me, when you line these two stories up side by side, they're interesting. One is a very in some ways, masculine story, right, of men who are under cover of night, conducting this secretive attack against the British Empire, but this was a group of women who in broad daylight, with no disguises, are demanding what they want, and what they wanted was coffee. To me, these two stories are a beautiful way to think about how much more diverse the impact of the American Revolution was on everyday people and how much more complex that story is, how much more there is to learn.

Kelly Therese Pollock 42:27

Michelle, thank you so much for speaking with me. I loved learning more about my beloved coffee, and it was really fun to read your book and speak with you.

Dr. Michelle Craig McDonald 42:37

It was my pleasure. Thank you so much for having me.

Teddy 43:02

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. Please subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app. You can find the sources used for this episode and a full episode transcript @UnsungHistoryPodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on Instagram @Unsung__History, or on Facebook @UnsungHistoryPodcast. To contact us with questions, corrections, praise, or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistoryPodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate, review, and tell everyone you know. Bye!

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

Michelle Craig McDonald is the Director of the Library & Museum at the American Philosophical Society. She has worked for nearly three decades as an educator and administrator in university settings as well as museums and historic sites.

Her research focuses on trade and consumer behavior in North America and the Caribbean during the 18th and 19th centuries—especially the history of coffee.