Genealogy in Early America

Both Abigail Adams and Benjamin Franklin took trips in England to trace their family histories, and they weren’t alone among 18th century Americans, many of whom took a keen interest in genealogy and family connections. Joining me in this episode is Dr. Karin Wulf, Director and Librarian of the John Carter Brown Library, and Professor of History at Brown University and author of Lineage: Genealogy and the Power of Connection in Early America.

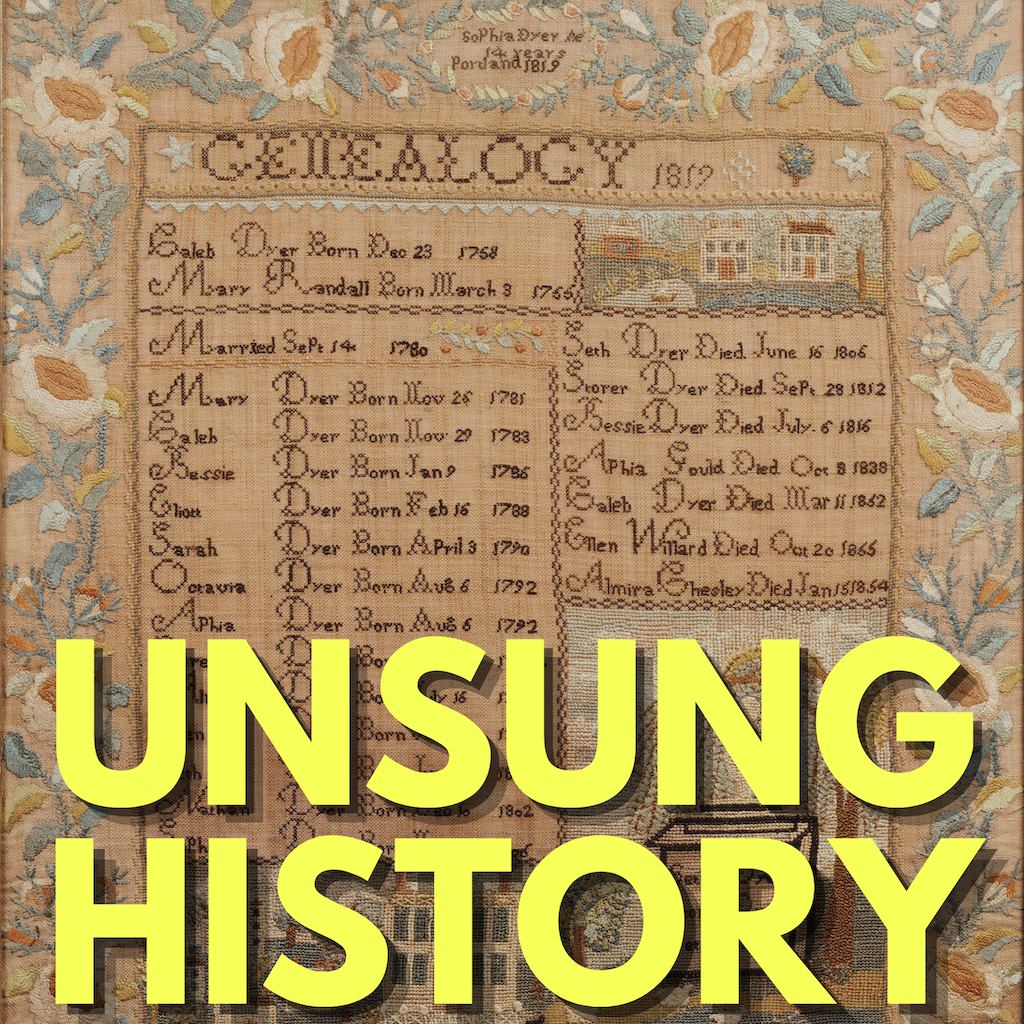

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The mid-episode audio is “Nothing like that in our family,” composed by Seymour Furth with lyrics by William A. Heelan and performed by Billy Murray on April 24, 1906; the audio is in the public domain and is available via the Library of Congress National Jukebox. The episode image is “Sampler,” by Sophia Dyer, 1819; the image is in the public domain and is available via the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Additional Sources:

- “Crossings- Abigail Was Here (Devonshire),” KathleenBitetti.com.

- “Benjamin Franklin to Deborah Franklin, 6 September 1758,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-08-02-0034. [Original source: The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 8, April 1, 1758, through December 31, 1759, ed. Leonard W. Labaree. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1965, pp. 133–146.]

- “Genealogical Chart of the Franklin Family, [July 1758],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-08-02-0029. [Original source: The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 8, April 1, 1758, through December 31, 1759, ed. Leonard W. Labaree. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1965, p. 120.]

- “Eliot’s Bible,” by Neely Tucker, Library of Congress Blog, August 6, 2024.

- “Isaiah Thomas Folio Bible, 1791,” Houston Christian University Dunham Bible Museum.

- “How Genealogy Became Almost as Popular as Porn,” by Gregory Rodriguez, Time Magazine, May 30, 2014.

- “Why Are Americans Obsessed with Genealogy?” by Libby Copeland, Psychology Today, October 13, 2020.

- “Our Story,” Ancestry.com.

Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brands

Kelly Therese Pollock 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app so you never miss an episode, and please tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers, to listen too. In the summer of 1787, Abigail and John Adams traveled from London to Devon in the southwest of England. At the time, John was the first United States minister to Great Britain, and Abigail was living with him in London. Abigail was not fond of London, and her doctor had advised her to travel for her health. She wrote that the visit was, "one of the most agreeable excursion I ever made," remarking, "The country is like a garden, and the cultivation scarcely admits any other improvement." It wasn't just a vacation, though. It was also a chance to see the county where her Quincy ancestors had lived, including a possible ancestor, the Saer de Quincy, Earl of Winchester, who was a signer of the Magna Carta. Although Abigail couldn't prove for certain that she was related to the Earl, she had reason to think she might be, because of the similarity between the Quincy Coat of Arms in Britain and those of her American Quincy family; and also because of family documents that had said that her family line traced back to William the Conqueror. Abigail and John Adams, like most of the founders, were keenly interested in genealogy. Abigail remembered amusing herself as a child with the genealogical table her grandmother had possessed. 29 years before Abigail Adams's genealogical journey, Benjamin Franklin took his own trip through England with his son to research family history for both the Franklin family and the Read family. Benjamin Franklin's wife was Deborah Read. With information he gathered from gravestones and parish records, along with what he already knew, Franklin wrote out a genealogical chart on a 15 inch by 20 inch piece of paper, tracing his line back to his great great grandfather, Thomas Franklin, who lived in Ecton in Northampton, in the mid 16th century, although the family may have lived there for a long time before that, as he wrote to his wife that Ecton was, "the village where my father was born and where his father, grandfather and great grandfather had lived, and how many of the family before them, we know not." From his success and eventual wealth, you may assume that Franklin was an oldest son, but as he wrote to a cousin, "I am the youngest son of the youngest son for five generations, whereby I find that had there originally been any estate in the family, none could have stood a worse chance for it." Inheritance, of course, was one major reason for people to track their family histories. But it wasn't the only reason, and long before Franklin and the Adams's traveled to trace their family stories, American colonists were recording family histories, often on whatever paper they had available, including in accounting books, almanacs and Bibles. Most of the Bibles in the colonies were Geneva or King James Bibles printed in England. Bibles were printed in the Americas, though, with the first being the Indian Bible, printed in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1663, by Puritan minister John Eliot. Eliot hoped that by translating the Bible into the previously unwritten Wampanoag language, he could convert Native Americans to Christianity. Rising tensions between the colonists and the Wampanoag people slowed conversions,and most of the copies of the Indian Bible were destroyed during King Philip's War. More recently, though, the Wampanoag Language Reclamation Project, founded by MIT trained linguist Jessie Little Doe Baird in 1993, has used the Indian Bible to bring back the Wampanoag language, which went extinct in the 19th century. Through the American Revolution, Americans were still reading British Bibles, but after the war, began printing their own Bibles in larger numbers. In 1791, Boston printer, Isaiah Thomas, publisher of the newspaper Massachusetts Spy, printed an American Bible with all of the engravings done by American engravers. Benjamin Franklin, called Thomas "the Baskerville of America," after the famous printer and type designer John Baskerville of Birmingham, England. Thomas put a lot of time and effort into deciding on the correct text for the Bible, and he also included an innovation, pre printed pages at the front of the Bible, for families to record their genealogical data. Prior to that, people had simply been using blank pages or open spaces to keep these records, but now Thomas gave them columns for Family Record of Marriage and Births of Children, and Family Record of Deaths. Families used these pages differently, even with the pre printed columns. Ebenezer Lamson's Bible of 1794 included not just the dates of his children's births and their marriages, but also a self portrait he drew.Thomas's own children had copies of the Bible and recorded family information in them. Some of these early Americans may have been just as genealogy obsessed as their modern counterparts, but they couldn't have predicted how big of a business genealogy would become. After Alex Haley published "Roots" in 1976, interest in genealogy skyrocketed, and by 2014, genealogy was the second most popular hobby in the United States, after gardening. One of the largest of the genealogy websites, Ancestry.com, began in the 1980s as Ancestry Publishing, producing genealogy reference guides and family history magazines. It now boasts over 30 billion records in its online database, and millions of users. In 2020, the Blackstone Group, a global asset manager, acquired a majority stake in Ancestry.com in a deal worth $4.7 billion. Joining me in this episode is Dr. Karin Wulf, Director and Librarian of the John Carter Brown Library, and Professor of History at Brown University, and author of, "Lineage: Genealogy and the Power of Connection in Early America."

Dr. Karin Wulf 8:38

Hi, Karin. Thanks so much for joining me today.

Dr. Karin Wulf 8:45

Thank you so much for having me on the podcast. I'm delighted to be here.

Kelly Therese Pollock 9:27

I would love to start with just hearing a little bit about how you got started on this project. You, of course, have written several other books. So what got you started on this one?

Dr. Karin Wulf 9:37

I suspect that my story is like a lot of historians. I started out pulling one archival thread and then continuing to pull it. And in my case, I started pulling that thread a long time ago. This book took a long time to write, and I've done some things in the meantime, but that archival thread, or I guess it's fair to say, it was really a scrap, was really little bits and pieces of paper, 18th century scraps of genealogical research that I was finding in families that I was looking to for other information. I was researching other subjects, and I kept finding these little bits and pieces of what looked a lot like the kind of genealogical research that many of the folks, in fact, who were sitting at tables right next to me in the same libraries and archives were producing where we're working from. And I thought, What are these 18th century people doing? Don't they know, as I thought I did know, that genealogy doesn't really get going as a kind of practice until the 19th century? Don't they know that in the 18th century, they're living in the world of increasing individualism and nuclear families, and why would they possibly care about these kind of extended kin and lineage connections? Or at least that's what I thought then, and I just was curious, and just kept kind of digging. And I think part of what happened is that, for me, genealogy becomes the subject that is absolutely everywhere in the 18th century archive. And once you see it, you kind of can't unsee it. And it's in so many different kinds of archival material that pulling that thread became more like loading a backhoe and feeling like, "Oh my gosh, there's so much. And how do I even begin to think about this in a comprehensive way?"

Kelly Therese Pollock 11:28

How did you go about doing that research, then? Because a lot of what you're finding is hidden inside people's account books or their Bibles. How do you go about finding it?

Dr. Karin Wulf 11:39

Yeah, it's so it's kind of funny, because in some ways it's like hidden in plain sight. The account books are a great example. So thanks for mentioning that. People have often asked me, How do you know how to find people's family records from the 18th century if they're not stored in the places that we might typically think of, like in family Bibles, which aren't really a major phenomenon until much later in the eighteenth century, really at the end of my period. So how did I find them? And so one thing that happened is I started identifying kind of genres and formats where family history could be found. And rather than being described as genealogies, they were described as something else. So an account book's a great example. I would go to a library or an archive, and I'd ask, "Can I see basically all your 18th century account books?" And I would know that I could mostly open those account books, either to the middle or to the end, and find a family record there. I mean, not always, but very regularly, but in the in the cataloging, in the subject description, in the description of the particular item, genealogy didn't show up there. So that family history was there the whole time. It wasn't hiding, except insofar as our understanding and description of the item sort of kept it a little submerged.

Kelly Therese Pollock 13:01

I suppose there's a more basic question. If we think of genealogy as something that didn't start until the 19th century, but you found that, in fact, people were doing this in the 18th century, what is genealogy and what is its relationship with the academic study of history?

Dr. Karin Wulf 13:18

You know, it's funny, because a friend of mine recently said, "Oh, Karin, I love how you describe that. Like genealogy is like the kind of formal recording, but family history is like the stories people tell". And I was like, "Did I say that? I don't know that I said that." I think that, you know, I sometimes use genealogy and family history almost interchangeably. Genealogy is the dictionary definition of it is an account of ancestry. So when people talk about parents, my grandparents, my great great grandparents, all of that is genealogical. And as you know, in the book, I talk a lot about, in fact, one of the chapters is titled, "Vernacular Genealogy," which is also the title of my Instagram account, where I put a lot of stuff too. But I use that term vernacular genealogy because I think it captures a way of thinking about less formal genealogical production than we may think of as became slightly stereotypical and probably not even the real story in the 19th century either, but when people started organizing geological societies and started producing enormous family volumes with some of the kind of old settler families and their longer lineages that could be discovered and then documented and then printed. Thank you, you know print revolution of the 19th century, cheap print revolution of the 19th century, but what people were doing in the 18th century by tucking something in their account book, or by keeping a little record with an object, or any one of the other myriad number of ways that I've described here, that was also genealogy.

Kelly Therese Pollock 14:53

Many of the records that we have, of course, are written by men, because most of the records that we have period, are written by men, but you have found genealogies from the 18th century by women as well. Can you talk some about the different ways that men and women were approaching genealogy?

Dr. Karin Wulf 15:11

Yeah, you know, it's kind of a tricky question, because, of course, as with all things archival, it matters a lot, what we're left with and what we think the whole, the totality was before the selection process of preservation, cataloging and institutional records production. So what did the whole picture of genealogical production look like? Like, was there a difference between how many men versus how many women kept these records? Maybe in the sense that one clear pattern I identified was that men who had what I would call chronicling lives, men who were ministers, or men who were town clerks, or lawyers, or school teachers who had lives in which they wrote a lot and they were expected to keep records in another way, often also kept family records, and women didn't often, or as often, have that same opportunity. So maybe there's a real difference there, but I think there's a real similarity in many of the formats that I see when women have account books, they keep family records in them too, these little hand sewn family records. Women created those too and of course, you know, women are really centrally important to genealogy in all kinds of ways. Women create genealogies and lineages through having children. And of course, in the cruelest inversion of this kind of very patriarchal society, heritable slavery, the status of slavery inheritable through the makes women, in many ways, the originating lineages for enslaved people, but women's lineages are important for all people too, free people as well. So there's a sort of like, "Do women produce genealogies and the records that we have differently? Are women different subjects of genealogy" These are kind of different questions, both hard to answer. I think the clearest thing I can say is that gender matters so much in genealogy, in the way that it does in almost everything in the 18th century, how people understand what's important, what kind of weight they give to certain things, and of course, how they hierarchically arrange people and ideas and objects, and then ultimately, archival stuff.

Kelly Therese Pollock 17:30

The modern genealogist, of course, can like go on Ancestry.com and say, "Find a birth certificate for me." How did these people in the 18th century, know so much about their lineage, about where they came from? There's no records for them to go look at in some cases, or at least no official legal records for them to go look at. There's no internet. How did they know what they knew?

Dr. Karin Wulf 17:57

So that's another great question that I think is so informed, and certainly my approach to it was really informed by the kind of idea that records and a modern record system really came out of nowhere in the 19th century, and in the mid 19th century in particular, and then the birth certificate and the birth certificate movement in the late 19th and early 20th century comes out of like, you know, the tatters of no record system. But the thing is, in the 18th century, people, of course, had record systems. It's just theirs look so different to ours. So let's start with one, which is people telling one another you're related to this person and that person. And that kind of oral testimony shows up in court records in all kinds of ways. Maybe one of the clearest examples is in freedom suits, or manumission lawsuits, where enslaved people want to document their descent from a free woman in order to kind of change their own status and the status of their children. And in many of those cases, it's really extraordinary the extent to which they can recount their lineages, particularly their maternal lineages, in quite detailed ways, and sometimes bring in testimony from folks to say," Yes, I knew that person. Yes, I knew grandmother. Yes, I knew them in the neighborhood," and so on. So, you know, we can never underestimate the value of families telling one another stories. That's just super valuable always, and we have the that kind of captured in those court records. And then secondly, every single colony required, and then state required keeping records in one way or another. They weren't always the same. So like in Pennsylvania, for example, there's this, like, great reference in the original Pennsylvania colonial law that just says, like, every denomination has to keep these records, and they're responsible for its births, marriages and deaths, what we think of as basic files, got to keep that stuff. And in other places, in New England, for example, they would say the town clerk is responsible for keeping these things in the town. But everyone had a requirement. Now, were they perfectly kept? No. Were they centralized? No, but people had a sense that there was a record system and that they could go to it and retrieve things. So, you know, I have found great examples of people writing to ministers, for example, and saying, "I would like to know, you know, what date my grandparents were married. Could you tell me?" Or Quakers, like famously fantastic record keepers for very specific reasons, but writing to the clerk of the meeting and saying, "I would like to know even about this aunt or uncle" You know where we might think like, that information may not be immediately critical, but for them, it was because they were doing this kind of genealogical framing. You know, this is not just like immediately, you know, my mother and my father. It's a kind of a wider thing. And then I guess just last, you know, as you know, I've had a hard time letting go of the research for this project to keep kind of going with it, which is part of why that Instagram account exists, so I can just keep putting stuff there. And I loved, especially finding more material here in Rhode Island, where I just moved, you know, three or so years ago. And I love to use an example from the Rhode Island Historical Society of a minister, this is in 1770, a minister who documented a marriage in his church. He wrote out details, this person married that person, and here's my information. But on the backside of that scrap of paper, which really is an extraordinary like little clue and it might not otherwise have survived. On the back of it, the town clerk recorded, "I got it, and I put it in the town record on this page." And then then I went and verified, yep, it is, in fact, on that page, and that's a fantastic thing, because it shows us this kind of process of record keeping. So there, there were records and people, people could use them, not perhaps in the fullest way that we think now, but truthfully, is there any record systemthat's perfect?

Kelly Therese Pollock 21:58

I have been doing some family research of my own, and my grandfather, so this is not that long ago, there is a dispute of what his birth date is. It's within one one week, one way or another. But, you know, he grew up thinking one thing, found a birth certificate later that said something else. And so I've done sort of a deep dive into well, this record says this. Well, this record says this, and which one should we trust and what's actually true?

Dr. Karin Wulf 22:22

Yes, I mean, I think that's such a great example, because, you know, we could so easily fall into the trap of thing that modern records are, you know, infallible when we know that, of course, they're not like, even when we think about like, the pressures on people to produce like census information now. You think about the kinds of ways that people feel resistant to information, very personal information that's being elicited from them or even extracted from them, and they may not want to provide it, you know. And they may, they may provide something that's not always like 100% accurate. Let's think about, you know, when people are being asked to authenticate their ages for certain things, and they don't always. So I think those record systems in the past were not perfect and were not complete and were not centralized, yes, but it's also not true that what we have replaced them with is somehow infallible.

Kelly Therese Pollock 23:12

You mentioned the Quakers and how much they did to trace family histories. Can you talk a little bit about why that was important to them, and how that then serves as a basis for us, in some ways, of keeping records going forward.

Dr. Karin Wulf 23:29

Yeah, it's such an interesting story. So that little archival thread that I really began with was when I was working on a group of Quaker women who were writers in 18th century Delaware Valley. I was really interested in them. And many of them are related, one to the other. And so, of course, I was like, always looking at they would refer to one another as cousin, and I'd be like, well, which kind of cousin? So I was trying to fill out family trees and so on. So I knew that Quakers would be important. And you know, I kind of had information from this group to start with. But what I hadn't counted on was that understanding the depth and the infrastructure of Quaker record keeping would be so revealing, and it's really important to understand that for Quakers, that record keeping practice originates in the late 17th century, and their founding as a really beleaguered, in fact, vulnerable denomination. You know, when the Quakers are founded in the late 17th century, they are under an enormous amount of pressure. In fact, they're being imprisoned for their beliefs, and part of what they're doing is they're starting to keep records, because they feel like that will make them less vulnerable to the state authorities in in England in particular. So they will say, one to the other, the Quaker founders, George Fox and then his his later wife, Margaret Fell, would say, "We must keep these records. You keep a separate record of marriages, just in case, and keep a record of births born to that marriage just in case." Now this goes to the point about like, why record keeping to so important for people and there are a whole variety of different reasons. Some of them are deeply emotional, but some of them are deeply practical. If a marriage is not recognized as legitimate, then the property from that marriage cannot necessarily be inherited by the children of that relationship. So keeping their own separate records, documented, witnessed, this is a huge thing for Quakers. Making sure everything is witnessed is really important. And so that thick Quaker record really begins right from the beginning, and they're very clear about that. Now there's another piece to this, which is that the Quakers are a birthright denomination. So knowing that a person was born to Quaker parents was equally important. And Quakers begin to move out into the wider kind of British imperial world and beyond, and establish different meetings. They also need to say, "Yes, you can be a member of the Quaker meeting because you're a Quaker. And we know you're a Quaker because you were born to this person and that person." So there's that, there's that dynamic too, but it really is this idea that they need to create a record system that makes them less vulnerable, basically, to the government, and that, I think, really interesting. And they, they so fit a broader British American practice. But even within that there, they have this distinctive quality.

Kelly Therese Pollock 26:24

You mentioned earlier, the hereditary nature of slavery in America. And of course, that goes through the maternal line. I think some people might have a thought in their mind that, well, enslaved people never knew where they came from, or it was impossible to trace back records. And of course, what you show in this book is that that may be true for some, but is is often not the case that they do very much know what their family line is. Could you talk some about that and the ways you mentioned freedom suits the way that that shows up and is important?

Dr. Karin Wulf 26:56

Yeah, you know, I often reference this because it was, was an important moment for me, but I had the opportunity to share a lot of this work with different groups as I was developing the project over this period of time. And one of the best questions I got was essentially about the nature of positive versus negative evidence. And it was like, "Okay, so Karin, you've got all these examples of people who produce genealogical information. What about people who didn't? Like are they like the silent majority? Kind of you know, how do you know that genealogy is so important if so many people, you know, you don't have evidence about their participation?" And my answer to that, really, is that people, some people, may not have cared about genealogy, per se, but genealogy always cared about them. That is that the structure of British American law and society and governance was so deeply and profoundly structurally committed to genealogy in all these kinds of ways. The law was so fundamentally about inheritance and property, including around slavery, that knowing one's family relationships was extraordinarily important, or knowing someone else's family relationships, or insisting on the documentation of other people was really important. So when it comes to enslaved people, of course, and this is true for indigenous people too, or even to a lesser degree, from other kinds of European kinds of cultures like the Dutch or the French or whatever, who had slightly different legal systems than the British. These were, nonetheless all groups that had to participate within a British American genealogical context, which was really framed by the particularities of its law, which is really patriarchal, very focused on lineage and very focused on on property and inheritance rights. So I know this is like a long way around answering your question about like, "But what about enslaved people?" So it is absolutely the case that enslavers kept records of how people were related one to the other, because that documented their property and both their property access, their property rights, and even when there were disputes. But through so many of these cases, we hear the evidence of enslaved people's understanding of their family relationships. Now we also know that, you know, transatlantic slavery ripped families apart and in one of the cruelest things, which I think extraordinary group of feminist scholars have shown, I think about Jessica Marie Johnson and so many others, Marisa Fuentes and so many others, one of the cruelest pieces of transAtlantic slavery is to really rip kinship from its meaning and yet to ask people to reconstruct, or to expect people to reconstruct, emotional connections and family connections within this unbelievably cruel context. But we know that people, some people, really did, and we know that they were able to recount those relationships, and that those relationships were both emotionally meaningful and also had instrumental value, just as they did for all people existing within this kind of British American genealogical regime.

Kelly Therese Pollock 30:03

As the American colonies become the United States, and there's theoretically this focus on, you know, we don't have kings and a lineage doesn't matter. We don't have royalty. One might expect that there would be less interest in genealogy. But of course, as you show all of the founders were also super interested in genealogy. How do we explain that or understand what's going on there?

Dr. Karin Wulf 30:29

Yeah, thank you. That's a great question. You know, I have said that I had kind of two aims with this book. I wanted people to begin to think about genealogy differently, both not as this kind of private hobby sort of entertainment thing, but as something that is just much more deeply, profoundly and publicly important, and having obviously a longer history. And I wanted people to think about early America differently, too, because those two narratives, as I suggested in one of our earlier exchanges, those two narratives about like genealogy really starts in the 19th century, and, you know, early America, the 18th century is like this great age of democratic individualism and so on. Those narratives worked against my understanding of this, of this topic. And I think they, they work against it for all of us, like we would expect people like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson and so on to be like, " Why would I care about lineage? I'm like, you know this new man. I'm this, like, you know, new emblem of democracy." But Ben Franklin, he writes this autobiography that we often talk about as emblematic of the new American, and yet that autobiography begins with an account of doing a genealogical research trip with his son. So we have just really seen past it. It's, I guess, the power of these narratives is really profound. You know, it was really hard for me to find any of the so called founding fathers who weren't interested in genealogy. I have yet to find one. You know, really, I can just amuse myself by finding yet another one, and then just, you know, kind of scrub around a little bit, and you find that, of course, they were, because they needed to. They needed to understand their family relationships in order to understand their own situation in the world, whether that was financial or otherwise. Just the other day, I was reading it, just as an exercise, and I was trying to find something from the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. And I read a series of exchanges of a woman with her brother, who's a soldier in 1775 to 77 and she says to him, she's in Philadelphia. It's a merchant family, relatively recent immigrant, Irish immigrants. And she says to him, "Hey, you know what? Our relatives actually are related to General Washington's wife. And you might just subtly drop that hint, like I'm going to tell you all the ways that we're related. So it's like from him to him to him, and ultimately, it's like a second cousin thing. You don't have to say all that. You can just say casually that you may know from a manuscript of your grandfather's that, you know, yes, there was this shared name." So it's like, it's a kind of a currency. It's a language that people adopt to explain their connections one to another. And they're not always so kind of openly instrumental about it, but it is. It is so thick in the culture that maybe we should never expect these so called founders to have not been invested, to have not been fluent in that language.

Kelly Therese Pollock 33:33

I loved the the part about Abigail Adams also going on a genealogical trip to England, and I saw in there that she was from or her family was from Devon. And I was like, "Well, I've got family from Devon too" And I looked it up, and I was like, "Oh, that was only, like, five miles away. Maybe I'm related to Abigail Adams." I think it's more likely my family, like, worked for her family. But you know.

Dr. Karin Wulf 33:56

All the connections, all the connections, yep, yep. That's one of fun things, actually, in just getting to talk to people about the book, finally, and not just talking in my own head or to my, you know, my my peer reviewers for the press or so on, is that so many people have fantastic stories of their experience of doing genealogical research, of thinking about what genealogy means to them, of how they've encountered people, of how they're connecting with this kind of 18th century practice, both in its kind of fantastical qualities, but also in its horrifying quality, frankly, too.

Kelly Therese Pollock 34:28

Maybe we could talk just more broadly about why family history is important, why more people should be thinking about family history instead of just maybe institutional history or something. You know, when I started this podcast, I always joked that, like, "I want to know everything else, not just the presidents. So obviously the presidents show up here, but it's a much bigger, more important, more monumental story, I think, than what you might get if you just sort of follow the presidents.

Dr. Karin Wulf 34:57

Yeah, thank you. I keep telling myself that one of these days, I'm actually going to start doing on social media what I do with my newspaper every day, which is to highlight all the ways that family is either a subject of policy or is a subject of a story. So family history, or an individual family's history, or the history of how we have thought about families is so deeply important. It's in some ways, like the failure of our discipline right to have said for centuries that what's important in history is like politics and economics and war, but not the thing that frames most people's existence, which is families in one context or another, sometimes a warm and supportive one, sometimes a really violent one, but also that governments have shaped themselves so profoundly around thinking about and trying to understand and trying to shape and restrain families for so long, it's really a loss not to be thinking about that. And, you know, I start to think about, like, "Okay, if, if these are the subjects that are so obvious in the archives, and yet we've kind of overlooked them, is that the same thing we're doing, like, with with family now?" And I think, yes, basically, yes.

Kelly Therese Pollock 36:18

I wanted to ask too, you were one of the founders of Women Also Know History, which I love, and I've used a lot when trying to find people to talk to on Unsung History. So I wonder if you could just talk about the impetus behind that, and what it what it works to do?

Dr. Karin Wulf 36:34

Yeah, I'm super proud of Women Also Know History, and a special shout out to Katy Telling who has been our social media manager for the couple of years, and done an amazing job. Keisha Blain and Emily Prifogle and I started Women Also Know History quite some years ago now. We were inspired by a political science group led by Christina Wolbrecht at Notre Dame called Women Also Know Stuff, which was profiled, I think, in the Washington Post, and I read it like I want to say, you know, was it in 2011, 2012, I don't know, something like that. And we read about their work to really highlight the work of women political scientists and to kind of create a kind of media tool. So we got in touch with Christina and said, "Could we do Women Also Know History?" And now there's like, Women Also Know Law too, which is very cool. And em has been involved in that as well, but it's a media and curriculum tool for highlighting the work of women and minority historians, and we feel like it's been really important, because, though things are getting better, the typical stereotypical idea of a historian has long been a white, older guy wearing tweed, you know, and elbow patches, actually, I think it was always like Harrison Ford in those movies, right? It's like, actually, he's an anthropologist, but, but anyway, so we wanted to create a site where people could build profiles and share their expertise, and then journalists and others, including other folks who were trying to find other people for like, conference proposals and stuff like that, could locate one another. And it's been great. You know, there's, I don't even know how think it's like 6000 scholars who are listed on the site now, which is, is pretty great.

Kelly Therese Pollock 38:12

I want to encourage listeners to read, "Lineage." Can you tell them how they can get a copy?

Dr. Karin Wulf 38:17

Oh, thank you so much. So you can order directly from Oxford University Press, your local independent bookstore, highly encourage your local library. Some of the most fun things I've heard from folks recently over the last several weeks, since the book was published on July 2, is people telling me that their library had a couple of copies, but it's got a waiting list. I was completely thrilled. Anyway, that's that's absolutely the best. So thank you all very much.

Kelly Therese Pollock 38:45

Is there anything else you wanted to make sure we talk about?

Dr. Karin Wulf 38:49

I'm just I'm so happy to have a chance to rattle on about this thing that has been in my head for so long. And I'm so happy to have like readers and listeners to talk to. People you know have been contacting me through my website, karinwulf.com, and that is super fun, too. I've been learning so much about people's thoughts about genealogy. It's been great,

Kelly Therese Pollock 39:07

Karin, thank you so much for speaking with me. Thank you for having me. It's been great.

Teddy 39:33

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. Please subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app. You can find the sources used for this episode and a full episode transcript @UnsungHistoryPodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on Twitter or Instagram @Unsung__History, or on Facebook @UnsungHistoryPodcast. To contact us with questions, corrections, praise, or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistoryPodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate, review, and tell everyone you know. Bye!

I’m a historian. And I know how important our sense of the past is to how we understand ourselves, our communities and our society in the present, and what we imagine for our collective future. Here on this site and elsewhere I am writing and speaking about how the essence of history– exploring and revealing the past–is so vital for us all.

My research has long focused on how gender and family intersected with political ideas, practices, and structures in early America– and how that intersection is reflected in what and where and why people wrote. My research materials are mostly texts, but often text that appeared not in printed books of the period, or not even in letters or diaries, but in other formats and genres. Like commonplace books, account books, almanacs, notebooks.

My new book Lineage: Genealogy and the Power of Connection in Early America was published by Oxford University Press in the summer of 2025. Lineage is about how early Americans represented their family histories and what that tells us about that foundational era. I’m working on several projects now, including another on genealogy that is both more capacious –genealogy across time and space–and quite brief; it’s for OUP’s Very Short Introductions series.

I’ve also researched and written academic articles that extend some of the work I did for Lineage. And I’m finishing research for a project about Esther Forbes, and her books including Johnny Tremain.

I write regularly for public audiences including ten years on the Scholarly Kitchen, and my writing has appeare… Read More