All in the Family

When All in the Family premiered in January 1971, CBS was nervous enough about the content that they added an advisory message at the beginning. Despite their fears, the show was a success, quickly garnering both awards and top Nielsen ratings. All in the Family not only changed television in the United States but also the practice of politics. Joining me in this episode is Dr. Oscar Winberg, Postdoctoral Fellow at the Turku Institute for Advanced Studies and the John Morton Center for North American Studies at the University of Turku, and author of Archie Bunker for President: How One Television Show Remade American Politics.

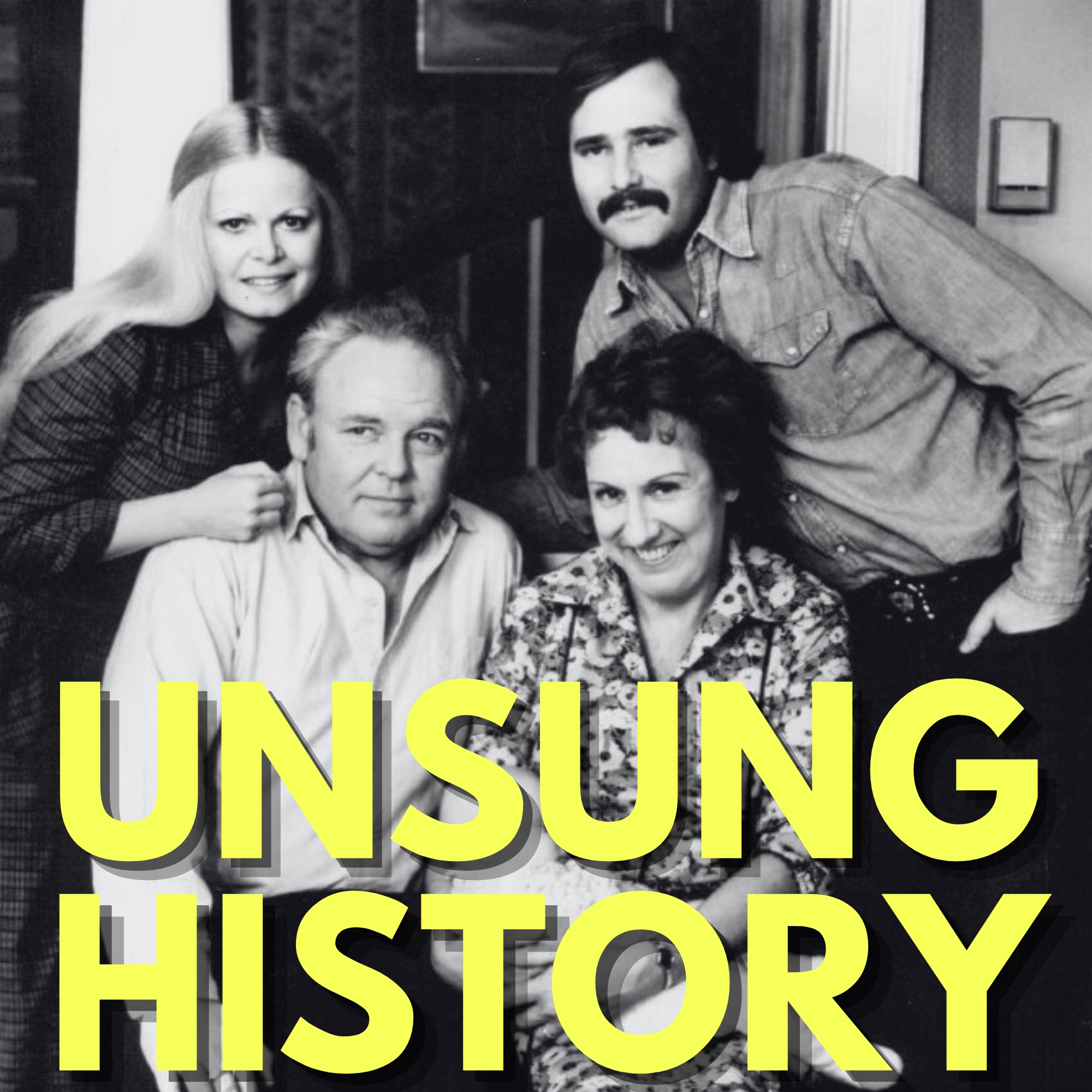

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The mid-episode music is “I Don’t Like Your Family,” composed by Joseph E. Howard, with lyrics by Will M. Hough and Frank R. Adams; this recording, from October 4, 1906, is in the public domain and is available via the Library of Congress National Jukebox. The episode image is a photo of the Cast of the television program All in the Family from a press release dated March 12, 1976; the photo is in the public domain and is available via Wikimedia Commons.

All in the Family streaming:

- Meet the Bunkers (Season 1, Episode 1) on YouTube

- Seasons 2 and 3 on Pluto TV

- Seasons 7 and 8 on Tubi

Additional Sources:

- “Till Death Us Do Part, 6 June 1966,” History of the BBC.

- “Norman Lear, Whose Comedies Changed the Face of TV, Is Dead at 101,” by By Richard Severo and Peter Keepnews, The New York Times, December 6, 2023.

- “For Good or Bad, Norman Lear Helped Erase Rural America from TV,” by Jeffrey H. Bloodworth, The Daily Yonder, February 22, 2024.

- “How Archie Bunker Forever Changed in the American Sitcom,” by Sascha Cohen, Smithsonian Magazine, March 21, 2018.

- “Looking Back on the Legacy of ‘All in the Family’ 50 Years Later,” by Tim Gray, Variety, January 12, 2021.

- “Looking Back on “All in the Family,” the Sitcom That Reshaped America,” by Tim Brinkhof, The Progressive Magazine, May 30, 2024.

- “Rob Reiner was more than a Hollywood liberal. He was a sophisticated political operator,” by Melanie Mason, Politico, December 15, 2025.

Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brands

Kelly Therese Pollock 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app so you never miss an episode, and please tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers, to listen too. In 1965, the BBC aired a pilot episode of a series that would become a long running British hit called, "Till Death Us Do Part." The sitcom, written by Johnny Speight and produced by Dennis Main Wilson, focused on the bigoted working class character of Alf Garnett and his relationship with his wife, his daughter, and especially with his son-in-law, Mike Rawlins, a socialist from Liverpool. American television director Bud Yorkin, saw the show and brought it to the attention of Norman Lear, with whom he had co founded Tandem Productions. Lear bought the rights to the show and developed an American version for ABC. After two pilots in 1968 and 1969, both starring Carroll O'Connor as Archie Bunker and Jean Stapleton as Edith Bunker, ABC passed on the show. In 1969, CBS named a new president of the television station, Bob Wood. Wood had previously run the CBS affiliate in Los Angeles, and then had run the division in charge of all five affiliates that were directly owned by CBS, all in major markets. He knew that the shows most profitable to CBS weren't always those with the best national ratings, but rather those most popular in the major markets where CBS owned and operated the affiliates. The Federal Communications Commission, FCC, limited the number of those markets. Wood's innovation was to purge the network of some of the longest running shows popular in the rural markets, including Hee Haw, Green Acres, and the Beverly Hillbillies, to make room for shows that would appeal to a younger, more urban audience. It was against this backdrop that Wood screened All in the Family, at the urging of his programming department. Wood was ready to take a risk on the controversial show, and set about convincing the regional affiliates to air the show. It still starred O'Connor and Stapleton, but now added Sally Struthers as their daughter, Gloria Stivic and Rob Reiner as her husband Mike. On January 12, 1971, the first episode of All in the Family hit the airwaves, starting with an advisory message, "The program you are about to see is All in the Family. It seeks to throw a humorous spotlight on our frailties, prejudices and concerns. By making them a source of laughter, we hope to show in a mature fashion, just how absurd they are." The network was prepared for a barrage of complaints about the show, but that first week, there were fewer than 1000 calls, a much lower volume than expected, and more than 60% of those had positive things to say about the show. Part of the minimal reaction was because very few people had even seen the show. It didn't break the top 40 in Nielsen ratings that week. For their part, critics were conflicted. Although most thought the show was clearly different than what they had seen before in its willingness to tackle topics that most other TV wouldn't touch at the time, some were offended, with one AP reviewer calling it, "a half hour of vulgarity and offensive dialog." Countering that view, Jack Gold, one of the most respected TV writers of the time, wrote in the New York Times, "Some of Archie's words may chill the spine, but to root out bigotry has defied man's best efforts for generations, and the weapon of laughter just might succeed." In May, 1971, just four months after it launched, All in the Family won the Emmy for Outstanding Comedy Series, and within a month, it became the number one show in the country. During its nine season run, All in the Family would garner 55 Emmy nominations and 22 wins, with all four lead actors taking home Emmys, in addition to wins for writing and directing. Audiences liked the show as much as critics did. It topped the yearly Nielsen ratings from 1971 to 1976, the first show in Nielsen history to do so for five consecutive years. The show was so popular that multiple shows spun off from it, including Maude, which followed Edith's liberal cousin, Maude, played by Bea Arthur. Maude, which also tackled controversial issues, ran for 141 episodes across six seasons, from 1972 to 1978. The Bunkers' African American neighbors, the Jeffersons had their own spin off, which ran 11 seasons and 253 episodes, making it perhaps even more successful than the original. Maude and the Jeffersons spawned their own spin offs, Good Times and Checking In, respectively. And after the end of All in the Family, two continuation shows followed, Archie Bunker's place and Gloria. There was even a show in the 1990s that was set in the Bunkers' house at 704 Hauser, though, without any of the original characters. One critic of All in the Family was none other than President Richard Nixon, who stumbled across the show while trying to find a rained out baseball game. He called the show, "the damnedest thing I've ever seen," and fumed over a gay character, ranting to White House Chief of Staff, H. R. Haldeman and domestic affairs advisor John Ehrlichman, "God damn it. I do not think that you glorify on public television, homosexuality. You see homosexuality, dope, immorality in general. These are the enemies of strong societies." Today All in the Family is generally regarded as one of the best American TV shows of all time, with several best of lists ranking it in the top 10. While the Smithsonian doesn't have a ranking of TV shows, the National Museum of American History does display Archie and Edith Bunkers' easy chairs in the museum, demonstrating the show's importance to our national history. Joining me in this episode is Dr. Oscar Winberg, Postdoctoral Fellow at the Turku Institute for Advanced Studies and the John Morton Center for North American Studies at the University of Turku and author of, "Archie Bunker for President: How One Television Show Remade American Politics."

Speaker 1 9:33

Hi, Oscar. Thanks so much for joining me today.

Dr. Oscar Winberg 10:15

Thank you for having me.

Kelly Therese Pollock 10:17

I would love to hear a little bit about how you got started on this project and decided to write what I believe was first a dissertation and then a book on All in the Family.

Dr. Oscar Winberg 10:30

Yeah, it was indeed first my dissertation and but to really understand the roots of it, we need to go all the way back to my childhood, because I grew up in Helsinki, Finland, and in the afternoons, having gotten home from school, television was, of course, a presence in my life and in my sort of early teen years, there started a new television, commercial television channel in Finland, and they bought up a lot of old American shows so that they could run them in sort of syndication in the afternoons, just to have programming. And that was where I first came across All the Family. I found it really interesting, the show, the way talked about issues of the day, the political conversation, the arguments, and it turned out that my parents had watched that show back in the day when it originally aired, so it became sort of a topic of conversation at the dinner table for us, even though the show had been off the air for for decades at that point. And so, you know, I had this connection to All in the Family. And then, when I started thinking about doing a dissertation, originally, I just wanted to understand the relationship between mass media, and especially entertainment media and politics in the US. But the more I read, the more I sort of scraped the surface, I understood that All in the Family is the show to understand, if you want to understand how television entertainment became such a critical part of political life in the US.

Kelly Therese Pollock 12:08

So interesting to me that you grew up in Helsinki and saw this show, and I grew up in small town, Ohio, and had never seen this show. I'd heard of it, of course, but had never seen it. So obviously, I'm sure you've seen every episode, probably multiple times. But that's clearly not all you do to write a book like this. Can you talk some about the kinds of archives and materials and things that you looked at when you were writing this book?

Dr. Oscar Winberg 12:32

Sure, and so the big challenge often when working with with media history, and especially entertainment, media and television, in a very real sense, is the feeling of, where are your archives? And this is partially because television entertainment was seen as sort of low brow, not important. So you're not necessarily going to find the papers of television writers in a university library or an archive. And so this was something that I came up at when I when I started doing this research, and Norman Lear, the producer of All in the Family, his papers weren't available. He was still among us at that point, although he was in his 90s. And so I sort of tried to understand this story by looking first at what I would call traditional political history archives, so presidential libraries, the papers of political activists, the papers of members of Congress and so forth. And it's quite striking how often this entertainment television show or some connection to it pops out in the archives of Nixon or the Rockefeller Archives or senatorial papers and so forth, or even the Congressional Record for that matter. But then my sort of big break was when I was able to connect with Norman Lear whilst doing the dissertation, and he then invited me over to Beverly Hills to look at his archives. So it turned out that he had a private archive, and had been working for years and years with an archivist to sort of keep track of it. So there was this immense treasure trove of there were letters from from from audiences. There were letters from political activists. There were memos from program practices, the censors at the networks and so forth. So that really changed the way I was able to tell this story, gaining access to that that collection.

Kelly Therese Pollock 14:36

At this point, of course, it's sort of anything goes on TV, and so it may be a little difficult for listeners to understand just how groundbreaking this show was. Can you talk some about what TV looked like before Norman Lear came on the scene and started making not just All in the Family, but several spin off shows as well?

Dr. Oscar Winberg 14:56

Sure, and I think the first thing to sort of point out is that television really was broad broadcasting. It was mass, mass media. And so what I mean by that is we're talking about a time where there were three networks. Almost every household, virtually every household, had television sets, and they were in use several hours a day, and with the three networks dominating the market, it meant that the ratings, so the number of households you had watching shows for the most popular shows, were talking about like 30 or higher percent of all the households in the US watching a show. And that was very much the case with All in the Family and and we're at, like the the peak of that era, you could have over 50% of of the people watching television at that point of time, watching the same show. So it was really, really a mass medium in in that sense. But the other part, the part where All the Family is breaking boundaries, is and here it's, it's important to remember sort of the Red Scare of the 1950s, how that had impacted television entertainment, and the result of that, sort of the red channels publications and blacklisting of certain writers and talents was that a lot of political, almost all political stories had disappeared from entertainment television, and especially stories about civil rights, stories about feminism, gender equality, these kind of stories just weren't talked about on on on television entertainment. You know, there's some examples that I mentioned in the book. In the 1960s you couldn't mention a Bar Mitzvah on a sitcom because it sort of had that Jewish sense that they wanted to avoid. You know, on The Dick Van Dyke Show that aired in the early 1960s, the married couple at the center of the show could not sleep in the same bed and so forth. So this was a very sort of restricted environment in terms of what you could deal with, and then All the Family comes in and sort of breaks all of these taboos and introduces completely new norms in terms of what you can talk about and how you can talk about it.

Kelly Therese Pollock 17:21

And why did Norman Lear want to do this, like what? What was driving him in creating this kind of television?

Dr. Oscar Winberg 17:30

So Norman Lear is really when, when we get around to the late 60s, early 1970s Norman Lear is a very successful writer and producer, but he's also a veteran of television. So in the 1950s he has worked with Dean Martin, Jerry Lewis. He has worked with Martha Raye. He has worked with all of these sort of traditional performers in television that were forced into these restrictions that I mentioned earlier, of what you could talk about on television, but then he had broken out from the world of television into the motion picture industry, and had enjoyed success there as well, including an Academy Award nomination for a film he wrote called Divorce, American Style, and he had a three picture deal with United Artists at this point. So he was really about to make it in the movies, so to speak. But when he heard from his producing partner, Bud Yorkin, and heard about this British show called Till Death Us Do Part, and how it was introducing completely new themes, how it was engaging political conversations, and in particular how it was about a relationship between a father, a bigoted father, and sort of a bleeding heart son-in-law, he in that he sort of recognized his own childhood, his own family dynamics, and especially his relationship to his own father. So I think that is why he was so committed to doing this show, even though a lot of people were telling him, this won't be a success on television and you've got these movies waiting for you. Just go ahead and make movies, leave television behind. But I think this emotional connection that he had to the material, including sort of, you know, Archie Bunker on the show calls his son-in-law "meathead," which is something that Norman Lear's father would call him, or he calls his wife "dingbat," again, something Lear brought from his own personal, personal background to the show. So I think this personal connection, really was the reason that he kept at it, even though the first network that ordered pilots of it, ABC passed on the project.

Kelly Therese Pollock 19:50

I want to talk a little bit more about this idea of bringing the personal because that's one of the things I found so interesting that you write about is that in the writers' room, the writers were encouraged to sort of bring what happened to you, you know, what are you talking about in your own family? What's going on? Could you talk some about that? And I mean, that seems like it would be obvious that, of course, you write what you know, but that this is actually something that was innovative about what they were doing.

Dr. Oscar Winberg 20:18

Yeah, absolutely. And I think again here, let's keep in mind most of the writers on this show, especially in the early seasons, are these veterans of television, people who wrote for Jack Benny, Bob Hope, Lucille Ball, and so forth. So it's not that it's a new generation coming in seeing the sort of let's tell new stories, but it's rather they are being told you now have the freedom to tell those stories, to engage in those materials that you know so well, but hasn't been allowed on network television before. And Norman Lear really sort of pushed this on to the writers he had, he told them to tell the stories of them, like the stories they knew, as husbands, as fathers, as as sons and so forth. The writing room was mostly male at this point, but he also provided them with the New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, you know, magazines to get them interested in real life when writing, and you have some of the stories, some of the famous stories on the show are plucked from the headlines in the sense of they have conversations about issues in the newspapers, connect those to their personal life. One of these stories is a story about the plight of the elderly in the 1970s, which came from both a personal experience of one of the writers, or actually the director, talking about how his mother was having a hard time making ends meet, and then stories in the Los Angeles Times about a rise in shoplifting among the elderly. And so that got the conversation going, and it turned out to become a very funny sitcom script, but a script with a clear message. We're talking about this issue that that seems to be of relevance and have sort of political implications as well.

Kelly Therese Pollock 22:19

Archie Bunker, of course, is famously very bigoted, very outspokenly bigoted. And you talk some about this interesting dynamic of people saying, well, you know, this is just terrible. Other people saying, but you know, they're making fun of it. So this is good to shine a spotlight on it. What? What's happening in culture? How are people reacting to the show, both as it first comes out and then, you know, the it had a fairly long run. So what does that look like in the way that people are responding to it?

Dr. Oscar Winberg 22:52

Yeah, this is, this is the big debate when All in the Family comes on, on the air, what, how are we understanding Archie's bigotry? And I think, considering it's it's been quite a while since the show was on the air, it's important for for, you know, younger audiences, when they find the show, to to realize that Archie was bigoted because they wanted to make fun of or like deal with bigotry, and they wanted to show that bigotry is a losing strategy in life, so to speak. They they very deliberately came in to mock the idea of of bigotry. And so the initial reviews, I would say that it's a pretty even split between television critics who are saying, "This is great, it's doing it's doing something new, and this is actually smart and funny." And then about an equal number of television critics who are saying, "This is complete garbage, and it's it's hurtful. This will not solve any problems, it would only add to the problems that we already have." But then this conversation then moves from the television pages in the newspaper to the op ed pages to conversations in in various activist organizations, in living rooms, in schools, in churches, so forth. And as this conversation grows, you see that there seems to first of all, that means you have more sort of contextualizing of the message. So we know that audiences aren't watching All in the Family in a vacuum. If they are also following along these debates, whether it's in church or it's on Johnny Carson or in school, you have this contextualizing conversation that very clearly says you were meant to understand this as satire. You were meant to laugh at Archie Bunker, not with Archie Bunker. Sure. So that's first of all. The other thing is, there isn't really a consensus. Again, there's this split. The sort of activist groups that are most worried about this is the Jewish civil rights organizations and rabbis, whereas the traditional Black civil rights organizations, with the exception of Whitney Young of the Urban League, are actually quite happy with the show. They're saying stuff like, I don't think it has a huge impact, but if it has, it is doing more good than harm. And in fact, you can see also a lot of organizations, including the NAACP giving awards to Norman Lear and Bud Yorkin, the producers behind the show, because of this idea that that they are combating bigotry in a new way, using satire. But this conversation is really never settled. There is some audience response surveys and stuff like this, but it's very contradictory the results in those and so even today, I think the number one understanding among scholars and critics of All in the is that you came in with your attitudes and you left with those attitudes. It's not necessarily changing minds, but it's definitely not turning people into bigots or curing people from bigotry. I think that is kind of misleading in the sense of it's missing that contextual message where you have these conversation conversations all around you in the 1970s guiding you towards an understanding of Archie as the fool on the show. And of course, you know, a sitcom can make that message in many ways, which they did on all the family, Archie was famous for these malapropisms, making him not a figure of authority. You know, you have a laugh track that sort of guide the understanding of the shows. You can do, close up shots, reaction shots of Archie's face and Carroll O'Connor, the actor playing him, was really good at playing around just with expressions. So I think for the most part, and previous research also suggests that for the most part, the number of people who found Archie to be a hero and his bigoted views to be to be the right message were a very small minority.

Kelly Therese Pollock 27:31

As you write about in the book, the one area that they didn't do as well in at least at the very beginning of the show is in representing women and women's stories and feminism until they brought in an advisor, Virginia Carter. Can you talk about sort of how that came about, how they realized, no, we need to do a better job and and work to make the the women characters a little more well rounded and their stories better represented?

Dr. Oscar Winberg 27:58

Yeah. Because one of the things that is really striking if you watch the pilot episode or the first couple of episodes of All in the Family, is that while it is groundbreaking in so many areas, especially regarding politics and race and so forth, the gender dynamics are very old fashioned. So Archie is the breadwinner. Edith, his wife, played by Jean Stapleton, stays at home. The daughter, Gloria, she doesn't have a job, nor does she study, whereas her husband Mike is studying at college. So it is this very sort of old fashioned understanding of gender, and a lot of feminists actually did not like this at all, and complained and wrote letters to the producers, and perhaps most importantly, Bud Yorkin and Norm Lear's wives were both committed feminists and active feminists in the women's movement in Hollywood, and they didn't really appreciate this either. And so you can see that after that initial success of the show, where it becomes the number one show in the nation, and you have a lot of conversations around it, Norman Lear and Bud Yorkin determined that they actually need help to make sure that they're on the right side of history when it comes to the women's movement, and part of this is the fact that there aren't very many female voices in the production process. Most of the writing room is older or middle aged men, middle aged white men, I should perhaps add. And so what they do is Norman Lear hires the president of the National Organization for Women's chapter in Los Angeles, Virginia Carter, who is a former physicist, has no experience of television at all, but her job is to come in and make sure that the message is right on these shows. So for her, of course, this is a once in a lifetime opportunity as an activist to actually get to talk to an audience of 15 million people and more when when all of these spin offs and other shows become successful as well. And the remarkable thing is that her opinion actually matters. So she comes in, she reads the script, she comments, and she researches storylines, and she works with outside activists and advocates in terms of, how can we tell different stories? And the remarkable thing, again, when I was researching this, is finding how often they were willing to sort of compromise on the comedy, or at least rework the comedy, so that the message the agenda, is not lost. And that meant cutting lines that were funny but wasn't promoting the right kind of message. And so that work of Virginia Carter at Tandem is really quite, quite unique in television at that point. She becomes almost a standards and practices department within the production company, rather than at the network. And that is a lot of power and a lot of opportunity to determine what kind of messages about women and the women's movement people see.

Kelly Therese Pollock 31:23

We've been talking about politics in terms of, like political ideas and this activism of Virginia Carter, but as you write about in the book, All in the Family gets involved in, like, explicit politics, presidential politics, presidential campaigns. So what? What is happening there? Nixon obviously doesn't like the show a whole lot. Nixon doesn't like a lot of things, you know. So what? What happens when Carroll O'Connor, for instance, decides I'm going to get actively involved in campaigning, not just as Carroll O'Connor, the actor, but as Archie Bunker?

Dr. Oscar Winberg 32:02

Yeah, this is the really, really special thing. And I think it's the perfect storm. It's a moment in politics where the system is changing. The structures are changing. You're moving away from the sort of party system to a primary system and a more media or mediated system with consultants and strategists, rather than sort of party figures determining policy and strategy for campaigns. It's also a moment where television is changing, right? So you have this, this newfound political message on TV. And then you also have not only Norman Lear being an incredibly bold figure in wanting to address new conversations, wanting to make new things on television, both on the screen and sort of outside the screen. But then you have Carroll O'Connor, who, while he's playing the reactionary bigot, is actually a very, very liberal, almost radical left in his politics, and he's determined to use this newfound fame as Archie Bunker, the most recognized face in the nation, to advance his own political convictions. And so in 1972, the presidential primaries, he ends up endorsing John Lindsay. John Lindsay is this liberal mayor of New York who has recently switched from Republican to Democrat, and so as he's running in the primary, he doesn't have this strong base within the party, but rather is reaching out to media figures to try to navigate a successful campaign. And so he gets the endorsement of Carroll O'Connor. And in these ads that they make for for the media market, they sort of play around a little bit with this actor character distinction. But it is clearly O'Connor, the actor endorsing him, and then sort of signaling at his character at the end of the television spots. But when the fall campaign comes around, Lindsay obviously doesn't get the nomination, isn't even close to it, in fact. When the fall campaign comes around, George McGovern is the nominee of the Democratic Party, and he's struggling with sort of this, you know, the white working class that had been the backbone of the New Deal coalition for decades. His core, core base is students and anti war activists and minorities, much more so than this white working class, male working class, I should probably add. And so in the fall campaign, McGovern turns to to Carroll O'Connor, or, I should say, turns to Archie Bunker, because the ads that Carroll O'Connor is making for McGovern is no longer the liberal actor O'Connor, but rather he presents himself as a concerned conservative for McGovern. And this is actually a quite interesting strategy in a media environment that is fixated on entertainment and celebrity and so forth. Not only do you see McGovern, the candidate himself, saying, all we're asking for is that everybody who likes Archie Bunker votes for us. You know, tongue in cheek, of course, but still. But the endorsement is reported in newspapers all over the US as Archie Bunker endorses McGovern. And in fact, it is often in the headlines, tops the news that the former vice president and primary challenger Hubert Humphrey is endorsing McGovern so that in the old party system, the rival, the sort of stalwart of the party, endorsing McGovern would have been the big news, in this news mediated system, the endorsement of Archie Bunker is what tops the headlines, and then Nixon is a whole other story. We remember Nixon as as hating All in the Family, which he did. He hated most entertainment, television entertainment. He hated most media, in fact. But in in 1972, he becomes convinced by a good friend, a television producer in Hollywood that he knows very well. He becomes convinced that the satire isn't working, that people are actually cheering on Archie Bunker, and as Nixon understands Bunker to be a representation of his base, his political base, the silent majority, he sort of sees an opportunity here and tries to win the endorsement of Archie Bunker. He talks about how he wants to to cover the nation with images of him shaking hands with Archie Bunker in the Oval Office in the weeks leading up to the election. Of course, that doesn't happen. O'Connor is not the reactionary bigot. He is the liberal actor, and so he ends up endorsing McGovern. But you this, I think the fact that it's not just John Lindsay sort of trying out something new, but it's also McGovern, it's also Nixon. And then this continues in '76 and in 1980 as late as 1992, which is more than 12 years after the show ended, you still have Democrats turning to Archie Bunker for working class credibility and endorsement in ads.

Kelly Therese Pollock 37:32

When I texted my parents to ask if they had watched All in the Family, and of course, they had watched it, you know, every week when it was on, my mom said Archie Bunker was the original Donald Trump. And I thought, "Well, that seems a little unfair to Archie Bunker," but you make a compelling case in the book that All in the Family and the way that it starts to blur politics and entertainment leads to where we are today. I wonder if you could talkus through that.

Dr. Oscar Winberg 38:00

Yeah, so I think you know, Norman Lear would agree. Before he passed, he said that Archie Bunker was always a man sort of out of place, uncomfortable with society changing, but at his heart, he was a kind and a decent man. That's not how Norman Lear understood the current president, and said so openly, in fact, but I still think that Archie Bunker sort of paved the way for Donald Trump. And as you say, it's not about even if there are similarities between the two characters, sort of, who's the most famous bigot from Queens in the 1970s that was Archie Bunker. Today, it perhaps might, might be Donald Trump, but I don't think that connection is the reason that Archie Bunker paves the way for for Donald Trump, but more so this blurring of, you know, entertainment and politics, and especially television entertainment and politics, and that is something that All in the Family and Archie Bunker and Carroll O'Connor and Norman Lear are all set in motion by trying to use television to engage in conversations of political and social relevance. And they sort of, they try to use it for good. But over the years, what happens is, you know, if you if you look at the 1980s you already start to see politicians making guest cameo appearances on popular sitcoms such as Cheers or other other shows. This continues in the 1990s where you have Bob Dole on on Suddenly, Susan, I think, and you have Newt Gingrich on Murphy Brown, and you also have a political debate with between the vice president Dan Quayle and the show Murphy Brown, the character Murphy Brown, played by Candice Bergen. So this, this is shifting already in the 80s and 90s, and it's very much shifting sort of based on the example set by All in the Family. And then Donald Trump is perhaps the one who is most adept at using television entertainment to build an image. And he's of course, in the 90s on all kinds of comedy shows, from the Fresh Prince of Bel Air to The Nanny to Sex and the City and so forth, and that is why he's chosen to play the billionaire on The Apprentice, and then he leverages that into a political commentator role on conservative media, especially on Fox News, and that is the credibility that he stands on when he decides to run for president. And I think it's a it's an aspect we don't talk about enough, is how much that media representation of Donald Trump as this success story, how much that played a role in the 2016 primaries, and how many people were openly saying this to journalists at various Trump rallies were saying, you know, we've seen him on television being this successful businessman. Surely, that's who he is, and that's why we need him in the White House. So I would say that there is a clear line from Archie Bunker to Donald Trump, but it's not necessarily the one we immediately think of. It's more about structures and sort of how the lenses of political media and political storytelling change.

Kelly Therese Pollock 41:35

We are speaking just over a week after the tragic murders of Rob Reiner and his wife, and of course, you spent a very long time studying Rob Reiner as a subject. I wonder if you could talk some just about what, what he meant as an actor, as a director, as an activist, and what what he meant to you.

Dr. Oscar Winberg 41:59

Yeah, sure. So it was a really, really hard morning to wake up last Monday to the news that not only had Rob Rob and Michelle Reiner passed, but in such a violent and tragic way. I never met Rob Reiner. I should say I did have the chance to meet with Norma Lear and Virginia Carter, but we've never met with Rob Reiner, but he was this figure at the center of my my research, and I have spent hours and hours not only watching All in the Family, but oral histories with Rob Reiner, and, you know, reading news articles about him and correspondence that were in the Lear archives relating to him and his role. So it did feel like, while not a friend, not, you know, there's, there's a distance of course, but it still felt, felt like losing somebody, not not a friend, but losing somebody that you have studied for for, you know, a decade at that point, and it got me to thinking, because Rob Reiner was not only this great comedic talent and actor, but he was then became a very successful and respected director. And I think in many ways, he followed in the footsteps of both Norman Lear and Carroll O'Connor in his his interest and his commitment to engage political activism as well and political movements. And this is clear, you know, in my book. He endorses McGovern in '72. He works for the Equal Rights Amendment in the mid 1970s, but especially in the work after that, and how he spent in the 1990s and especially in the 21st Century, spent so much time and energy on political campaigns, and that's often forgotten, or it's seen as something, you know, some form of just celebrities trying to to meddle in politics, in a certain sense, but Reiner was really a key figure, for example, in the drive for same sex marriage in California, as well as other campaigns. And I think we need to understand this as as part of of his legacy, not only him being a director, not only him being an actor, but all of this tying together into these political campaigns as well.

Kelly Therese Pollock 44:32

Your book is fantastic. It's a really great read, even if people haven't watched a whole lot of All in the Family. I admittedly have only watched a, you know, handful of episodes and that in the past week. So I really want to encourage people to read it. Can you tell the listeners how they can get a copy of the book?

Dr. Oscar Winberg 44:50

So it's out from UNC Press and you can find it online, or, you know, just go to your favorite bookstore and ask them to order a copy.

Kelly Therese Pollock 45:01

And I'll put in the show notes as well a link to the book, but also a link to where you can watch some episodes of All in the Family, if this has encouraged people to want to watch or re watch. Is there anything else you want to make sure we talk about?

Dr. Oscar Winberg 45:16

I think we could talk a little bit about conservative campaigns against All in the Family, because All in the Family becomes this symbol of a certain type of entertainment. And when you talk about political issues, when you talk about social issues, that is always going to be appealing to some people and sort of off putting to others and from the get go, there are especially conservative, conservative viewers, but also conservative, you know, columnists and activists who are complaining about this bound, these boundaries that All in the Family is breaking. They sort of viewed them as as proper, proper boundaries for for such a broad medium as television. And this actually culminates in the mid 1970s with Congress pressuring the FCC, the Federal Communications Commission, to deal with violence and sex. And this is a very curious campaign, because the violence is mostly or the concern about violence is mostly coming from liberals and intellectuals. And it's important again here to note sort of historical context. This is only a couple of years after the assassinations of Robert F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King of John F. Kennedy before that and so forth. And there is this, this grave concern that television violence is adding fuel to the fire. And there are studies showing that young Americans growing up are watching numbers of murders every week on television. So that's the concern about violence. But then more conservative interest is able to sort of use this conversation to also talk about sex on television. And there really isn't any sex on television. I mean, no explicit sex on television in the 70s, even if All in the Family is breaking boundaries, also in that area, by sort of innuendo. There certainly is is no explicit sex on television. And then, after this policy is passed, it quickly becomes apparent that sex is not intercourse, but rather is conversations about pregnancy, conversations about contraceptions, conversations about birth control, conversations about homosexuality, conversations about women's rights. This is what conservative activists sort of are targeting when they want to stop immorality on television. I'm using scare quotes here, or when they want to go after improper sexual conversations, and because All in the Family is not only the most popular show, but the show that sort of symbolizes this turn to open conversations about these sort of themes. Norman Lear, the producer and and the actors of the show become very engaged in this court battle over this, this, what they call censorship, government censorship, of television entertainment. So I should say the policy that is enacted is called the family viewing hour. It says that the first hour of prime time will be reserved for entertainment suitable to a family audience, whatever that means, right? And so because of this policy, CBS has to move All in the Family out of its eight o'clock spot on the prime time lineup. And ultimately, this, this policy shakes up the whole whole prime time schedule. And so the Screen Actors Guild, the Directors Guild and the Writers Guild all together join in a lawsuit against the FCC and all the three networks over this policy, and they ultimately win. And part of that is part of their argument is always that we are now in the business of censoring ideas about sex, or themes ideas related to sex, and so obviously, Norman Lear is a towering figure in these conversations, as are other producers, such as Larry Gelbart of MASH and others as well. But it's really is striking how a lot of these conversations that we see today about, you know, panics about trans rights, for example, or other sort of conservative attack lines against against sexual minorities, against gender equality and so forth, are very much already happening in the 1970s and are proving to be immensely successful in recruitment and fundraising in the 1970s and so that's part of the legacy of All in the Family as well, is it's it proves to be a very lucrative bete noir for conservative activists.

Kelly Therese Pollock 50:16

Oscar, thank you so much for speaking with me today. I really enjoyed learning more about All in the Family. I enjoyed having the opportunity to go watch a bunch of episodes. So thank you.

Dr. Oscar Winberg 50:29

My pleasure.

Teddy 50:43

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. Please subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app. You can find the sources used for this episode and a full episode transcript @UnsungHistoryPodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on Twitter or Instagram@Unsung__History, or on Facebook @UnsungHistoryPodcast. To contact us with questions, corrections, praise, or episode suggestions, please email kelly@UnsungHistoryPodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate, review, and tell everyone you know. Bye!

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

I am a political historian, author of Archie Bunker for President: How One Television Show Remade American Politics, and currently a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Turku Institute for Advanced Studies and the John Morton Center for North American Studies at the University of Turku. I hold a PhD in history from Åbo Akademi University. In the United States, I have been affiliated with the American Political History Institute at Boston University.

My work has appeared in a variety of journals and popular outlets such as the Washington Post, The Conversation, and on NPR.