Black History Month

One hundred years ago, Dr. Carter G. Woodson created and launched the inaugural Negro History Week after his professors told him that Black people didn’t have a history worth studying. Negro History Week built on the success of Douglass Day and quickly spread through Black communities in the United States. Fifty years later, at the urging of the Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History, President Gerald Ford called for Americans to celebrate Black History Month, which was finally ordered by Presidential Proclamation in 1986. Joining me in this episode is Dr. Jarvis Givens, Professor of Education and African and African American Studies at Harvard University and author of I'll Make Me a World: The 100-Year Journey of Black History Month.

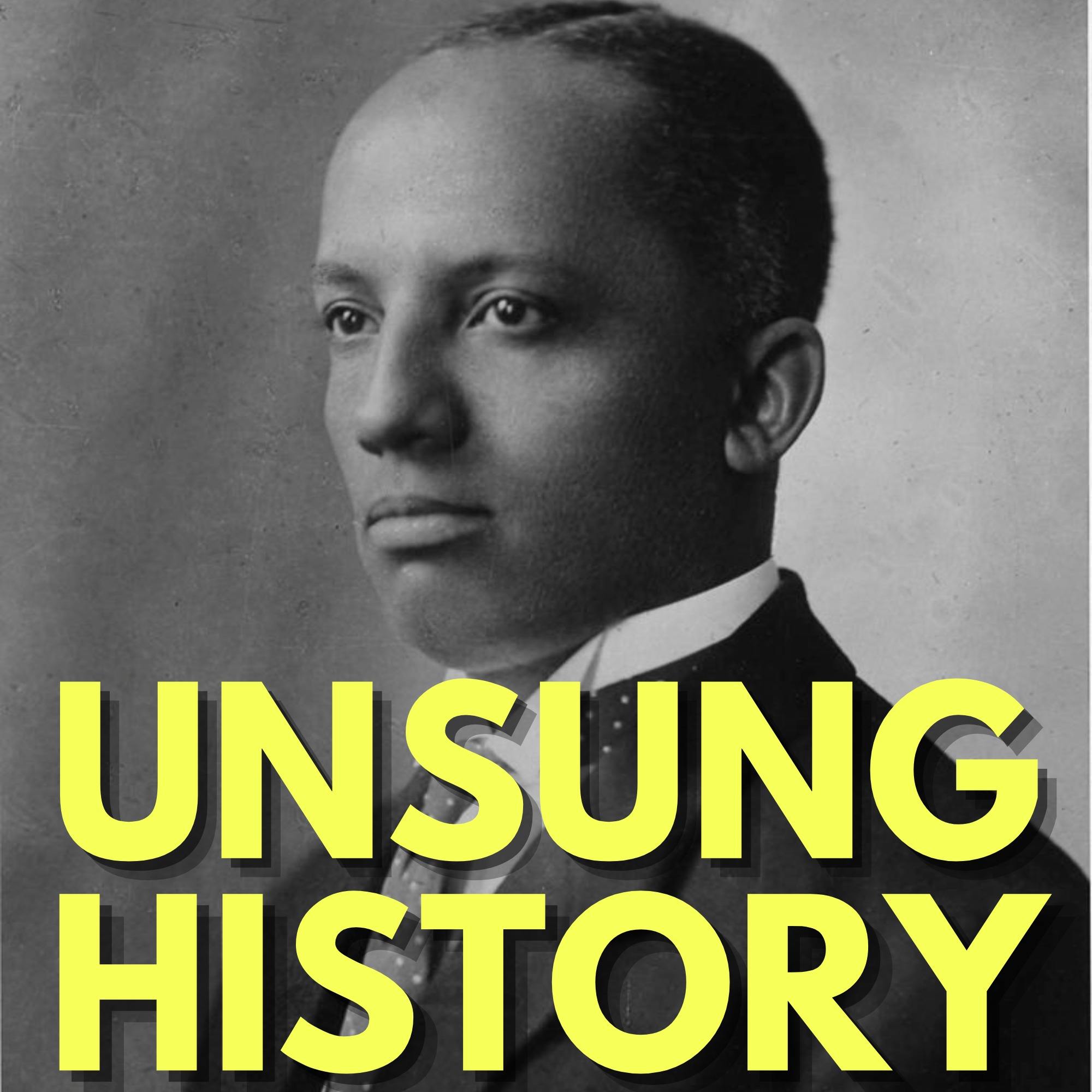

Our theme song is “Frogs Legs Rag,” composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The mid-episode audio is “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” with lyrics by James Weldon Johnson and music by Jon Rosamond Johnson; this public domain performance is by the United States Army Field Band and the 82nd Airborne Chorus and features Staff Sgt. Kyra Dorn. The episode image is a portrait of Carter G. Woodson taken on 19 December 1915 by Addison Norton Scurlock; the image is in the public domain and is available via Wikimedia Commons.

Additional Sources:

- “The Origins of Douglass Day,” by Jennifer Morris, Smithsonian Digital Volunteers, February 14, 2023.“The story behind the Frederick Douglass birthday celebration,” by Scott Bomboy, National Constitution Center, February 14, 2024.

- “Black History Month: A Commemorative Observances Legal Research Guide,” Library of Congress.

- “The Origins of Black History Month,” by Daryl Michael Scott, The Association for the Study of African American Life and History.

- “Here's the story behind Black History Month — and why it's celebrated in February,” by Jonathan Franklin, NPR, February 2, 2022.

- “W. E. B. Du Bois and Black History Month,” by Phillip Luke Sinitiere, Black Perspectives, February 18, 2016.

- “Message on the Observance of Black History Month, February 1976,” by Gerald Ford, February 10, 1976.

- “Proclamation 5443—National Black (Afro-American) History Month, 1986,” by Ronald Reagan, February 24, 1986.

- “Proclamation: National Black History Month, 2026,” by Donald Trump, February 3, 2026.

Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brands

00:00.031 --> 00:08.820

[SPEAKER_02]: This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention.

00:09.720 --> 00:12.543

[SPEAKER_02]: I'm your host, Kelly Theresa Pollock.

00:12.563 --> 00:19.430

[SPEAKER_02]: I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do.

00:20.591 --> 00:27.658

[SPEAKER_02]: Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app so you never

00:27.638 --> 00:32.845

[SPEAKER_02]: Tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers to listen to.

00:37.932 --> 00:43.980

[SPEAKER_02]: Abolishnessed and statesmen Frederick Douglass never knew when his birthday was.

00:45.262 --> 00:54.675

[SPEAKER_02]: There was no written record of his birth, and his previous since slavers had told him it might

00:55.904 --> 01:08.300

[SPEAKER_02]: He wrote in a letter in 1891, quote, it has been a source of great annoyance to me, never to have a birthday on quote.

01:08.320 --> 01:13.707

[SPEAKER_02]: He chose to celebrate his birthday on Valentine's Day, February 14th.

01:15.270 --> 01:24.021

[SPEAKER_02]: After Douglas' death in 1895, prominent black individuals sought to commemorate his remarkable life.

01:24.929 --> 01:47.258

[SPEAKER_02]: Educator and activist, Mary Church Terrell, suggested to the District of Columbia Board of Education on which she served that black children in DC should celebrate February 14th as Douglas Day to learn about his life into here his speeches.

01:48.470 --> 02:09.134

[SPEAKER_02]: in her remarks at the first Douglas Day celebrations, to rel describe Douglas as a leader, quote, who set a high standard of life and dared to live up to it in spite of opposition, criticism, and persecution on quote.

02:09.154 --> 02:16.182

[SPEAKER_02]: By the time Carter G. Woodson earned his PhD at Harvard University in 1912,

02:17.360 --> 02:20.665

[SPEAKER_02]: Douglas State was already observed nationally.

02:20.706 --> 02:43.924

[SPEAKER_02]: Woodson was born in 1875 to formerly enslaved parents, and he worked as a coal miner in West Virginia before attending Beria College in Kentucky, and then the University of Chicago where he earned his MA in European history in 1908.

02:45.170 --> 02:55.463

[SPEAKER_02]: at Chicago and at Harvard, Woodson's professors made it clear that they did not believe the black people had a history worth studying.

02:57.065 --> 02:58.206

[SPEAKER_02]: Woodson disagreed.

02:59.448 --> 03:06.217

[SPEAKER_02]: And in 1915, he founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History.

03:07.338 --> 03:12.865

[SPEAKER_02]: Now known as the Association for the

03:14.127 --> 03:18.011

[SPEAKER_02]: His co-founders were George Cleveland Hall, W.B.

03:18.051 --> 03:22.715

[SPEAKER_02]: Hartgrove, Alexander L. Jackson, and James E. Stamps.

03:24.317 --> 03:31.223

[SPEAKER_02]: In 1916, Woodson and the Association launched the Journal of Negro History.

03:32.645 --> 03:40.152

[SPEAKER_02]: And addressed by Woodson, helped to kick off an initiative by the Omega sci-fi fraternity chapters.

03:40.604 --> 03:46.831

[SPEAKER_02]: to celebrate Negro History and Literature Week from 1921 to 1924.

03:48.113 --> 04:02.089

[SPEAKER_02]: But Woodsen recognized that an initiative run through the association for the study of Negro Life and History would have broader reach than one organized by a fraternity.

04:03.284 --> 04:18.475

[SPEAKER_02]: In February of 1926, woods in created and launched the inaugural Negro History Week to counter anti-black narratives and to study and preserve black achievements.

04:19.577 --> 04:22.643

[SPEAKER_02]: And not just those by luminaries like Douglas.

04:23.888 --> 04:34.519

[SPEAKER_02]: Situating Negro History Week in February though was a direct nod to the tradition of Douglas Day that had already been established.

04:36.000 --> 04:50.875

[SPEAKER_02]: The celebration of Negro History Week grew quickly as it spread through existing communities, including black newspapers, black teacher networks, historically black colleges and churches.

04:52.120 --> 05:06.163

[SPEAKER_02]: By the early 1930s, Negro History Week was widely celebrated in Black segregated schools, and generations of Black students grew up with these commemorations.

05:07.426 --> 05:13.000

[SPEAKER_02]: In February 1949, Scholar and activist W.E.

05:13.081 --> 05:24.169

[SPEAKER_02]: B. DuBoys in a speech to the Workers Fellowship of the Society for Ethical Culture in New York City, praised Woodson's efforts.

05:24.149 --> 05:45.229

[SPEAKER_02]: saying, quote, this man standing almost alone has virtually compelled the people of the United States, at least once a year, to recognize the fact that a tenth of their population has developed a history worth knowing, unquote.

05:46.424 --> 06:05.817

[SPEAKER_02]: He further noted that Negro History Week brought vote to the attention of Negroes themselves to let them know that despite the silences and omissions and the distortions of history, Negroes in America have done a remarkable job.

06:06.252 --> 06:09.636

[SPEAKER_02]: in the personalities in which they have given to the nation.

06:09.697 --> 06:21.652

[SPEAKER_02]: In the contributions they have made to the nation's culture into the expressions which they have contributed to American art, unquote.

06:21.672 --> 06:35.871

[SPEAKER_02]: At the annual meeting of the Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History in October, 1875, noting that both the 50-year

06:36.425 --> 06:42.354

[SPEAKER_02]: and the 200th anniversary of American independence would fall the following year.

06:42.374 --> 07:01.504

[SPEAKER_02]: The association decided that in 1976, they would expand the celebrations to the entire month of February declaring the theme in 1976 to be America for all Americans.

07:02.733 --> 07:07.843

[SPEAKER_02]: In fact, in some places, Black History was already a month-long celebration.

07:07.883 --> 07:18.565

[SPEAKER_02]: For instance, the Black Students at Kent State University in Ohio had established their own Black History Month in 1969.

07:19.861 --> 07:46.813

[SPEAKER_02]: J. Rupert Pickod, a professor of history at Virginia State University, and executive director of the Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History, drafted a proclamation that they sent to President Gerald Ford's administration in hopes that he would issue a

07:47.840 --> 07:50.944

[SPEAKER_02]: such a proclamation requires congressional support.

07:52.466 --> 07:58.112

[SPEAKER_02]: And instead, Ford offered a presidential message on February 4th, 1976.

08:00.515 --> 08:12.109

[SPEAKER_02]: Although the message confused Woodson's birth year with the Year of the Association was founded and it failed to acknowledge the harm's done to black people in the United States.

08:12.663 --> 08:28.512

[SPEAKER_02]: For did write, quote, I urge my fellow citizens to join me in tribute to Black History Month, and the message of courage and perseverance it brings to all of us, unquote.

08:28.532 --> 08:36.426

[SPEAKER_02]: In February 1986, President Ronald Reagan issued Proclamation 5443.

08:37.115 --> 08:46.812

[SPEAKER_02]: which declared National Black, Afro-American History Month, as requested by Congress in Senate Joint Resolution 74.

08:48.755 --> 09:01.637

[SPEAKER_02]: The 1986 Proclamation opened by describing Black History as, quote, a book rich with the American experience, but with many pages yet unexplored, unquote.

09:02.798 --> 09:09.412

[SPEAKER_02]: Unlike Ford's earlier message, it acknowledged the suffering of black people in American history.

09:09.472 --> 09:23.642

[SPEAKER_02]: Explaining the purpose of black history month was, quote, to make all Americans aware of this struggle for freedom and equal opportunity, unquote.

09:23.622 --> 09:35.202

[SPEAKER_02]: And also, quote, to celebrate the many achievements of blacks in every field from science and the arts to politics and religion on vote.

09:36.397 --> 09:56.514

[SPEAKER_02]: In this 1986 proclamation, Reagan wrote, quote, the American experience and character can never be fully grasped until the knowledge of black history assumes its rightful place in our schools and our scholarship, unquote.

09:56.534 --> 10:05.982

[SPEAKER_02]: On February 3rd, 2026, President Donald Trump continued the tradition of presidential proclamations

10:07.109 --> 10:33.133

[SPEAKER_02]: Although the language returns to that of 50 years ago, ignoring the suffering and sacrifice of black Americans, and focusing instead on, quote, the contributions of black Americans to our national greatness, and their enduring commitment to the American principles of liberty justice and equality, unquote.

10:34.295 --> 10:52.793

[SPEAKER_02]: Joining me in this episode is Dr. Jarvis Givens, Professor of Education and African American Studies at Harvard University, and author of, I'll make me a world, the 100-year journey of Black History Month.

10:56.840 --> 11:12.739

[SPEAKER_05]: song, full of the faith that the darkness has told us, see the song, full of the hope that the crescent has brought.

11:18.457 --> 11:41.471

[SPEAKER_04]: Facing the rising sun, I'm a new day begun, let us march on to victory, is one.

11:41.491 --> 11:43.534

[SPEAKER_02]: I Jarvis, thanks so much for joining me today.

11:44.376 --> 11:45.898

[SPEAKER_00]: Absolutely, thanks for having me, Kelly.

11:46.216 --> 11:55.737

[SPEAKER_02]: I know you've written a lot of books, including one that came out fairly recently, so I want to hear a little bit about this book, what got you started on it, what your inspiration was.

11:56.948 --> 12:17.456

[SPEAKER_00]: Yeah, so I'll make me a world as it's about the 100 year journey of Black History Month, but the book is not just about, kind of, it's that chronically, you know, the development of what happened one year after another when it comes to the story of Negro History Week, which began in 1926 growing into Black History Month.

12:18.017 --> 12:26.348

[SPEAKER_00]: But it really, I was really using this

12:26.446 --> 12:49.365

[SPEAKER_00]: black history commemorations in February to take some time to reflect on the black historical tradition and African American intellectual traditions that informed the creation of Negro history week that became black history month because that thought it was important to engage readers and a conversation about what's at stake in the preservation of

12:49.345 --> 13:07.827

[SPEAKER_00]: on marginalized histories, particularly black history, and I thought that kind of going back to the origins of how something like black history as a field came to be and how this popular black history movement that was taken place by the 1920s that gave birth to Negro history week.

13:07.807 --> 13:25.258

[SPEAKER_00]: you know how something like that came about what it was responding to what the work that it was trying to do in the world at that time in the world of the future right and that's what this book was about especially in a moment where we're seeing all kinds of attacks on critical interpretation of history I thought it was important for me.

13:25.238 --> 13:53.997

[SPEAKER_00]: To try and seize this moment to talk about a tradition of scholarship that I've been I've been I've been a fit it so much from when I think about my own educational journey from a young student even to now the scholar and professor And I wanted to honor the best of that tradition and to write about it in a way that could invite new audiences to come in and to appreciate it and to understand why it's important to continue fighting for and protecting and expanding on this tradition in the current moment

13:54.584 --> 13:57.069

[SPEAKER_02]: You just mentioned your own educational journey.

13:57.289 --> 14:00.796

[SPEAKER_02]: Could you talk some about the teachers that you had along the way?

14:00.856 --> 14:14.402

[SPEAKER_02]: You say in the acknowledgments at one point, it was going to be like a collection of letters to your teachers, but they're obviously prominent in the book and they're clearly not just the people who taught you black history, but they themselves lived black history.

14:14.442 --> 14:15.865

[SPEAKER_00]: Absolutely.

14:16.225 --> 14:17.588

[SPEAKER_00]: Yeah, thank you for that, Kelly.

14:17.888 --> 14:43.069

[SPEAKER_00]: Yeah, when I, when I began working on this book and I actually have to say it's to get when I began working on this book, but also my first book, right, I think it's important to to name, you know, a fugitive pedagogy, cardogy, what's in the art of black teaching, that book was about me working to recast the narrative that we have about the history of black teachers

14:43.049 --> 14:48.539

[SPEAKER_00]: From my understanding, am I reading of the historical record, Black teachers played an essential role in the Black Freedom struggle?

14:49.020 --> 14:55.452

[SPEAKER_00]: But until very recently, they hadn't really been thought about as important shapers of that movement, right?

14:56.414 --> 15:03.167

[SPEAKER_00]: And when I was studying this history, you know, the story of Negro history, we can Black Kishimont became really important because,

15:03.147 --> 15:14.103

[SPEAKER_00]: It only expanded across the country when Carter G. Woods created in 1926 because of this networked world of African-American teachers living in the context of Jim Crow America.

15:14.804 --> 15:23.716

[SPEAKER_00]: So I'm saying all that to say is that for my education of journey, you know, I grew up in Compton, California, began going to school in the early 1990s.

15:23.776 --> 15:32.749

[SPEAKER_00]: And I attended a small black independent school, a small black croquio school in Compton, California,

15:32.729 --> 15:54.973

[SPEAKER_00]: And I didn't appreciate what I was born through the experience, but all of the students at the school were black and all of the teachers and administrators were black, both from the US and also from various parts of the diaspora and my preschool year, my very first schooling experience, you know, I write about this in the book, like history month was one of the kind of, was one of the,

15:54.953 --> 16:02.048

[SPEAKER_00]: really one of my big introductions into school and the kind of academic culture of this institution that I attended.

16:02.068 --> 16:11.308

[SPEAKER_00]: In my teacher I write about her a woman named Miss Myron Rook Butterfield who still lied to his day and she came to early childhood education very later in life.

16:11.288 --> 16:28.318

[SPEAKER_00]: But I'll never forget how she prepared us as pre school students to recite excerpts from Martin Luther King Jr.'s, I have a dream speech and how far we rehearsed for this performance before our schoolmates, our community members, our parents, right now it's just this huge event.

16:28.298 --> 16:31.927

[SPEAKER_00]: But that wasn't the only time of the year that we learned about Black History.

16:32.167 --> 16:38.583

[SPEAKER_00]: Every single morning before we went to school, part of the morning devotion we had to recite, arms by Black writers.

16:39.084 --> 16:43.013

[SPEAKER_00]: Like dreams by links and shoes, every single day from preschool to eighth grade.

16:43.454 --> 16:44.637

[SPEAKER_00]: We had to, you know, you know.

16:44.617 --> 16:45.858

[SPEAKER_00]: Do the pledge of allegiance.

16:45.878 --> 16:47.940

[SPEAKER_00]: We also had to sing Lift Every Voice Insane.

16:47.960 --> 16:56.609

[SPEAKER_00]: So from the time I was a very small child, I thought that part of going to school meant, you know, you have to say the pledge of allegiance, but you also sing Lift Every Voice Insane.

16:56.669 --> 17:01.613

[SPEAKER_00]: You also recite these poems that you, you're supposed to recite with all this emphasis and all this energy.

17:01.914 --> 17:03.315

[SPEAKER_00]: And that's how you begin the school day.

17:03.956 --> 17:04.176

[SPEAKER_00]: Right?

17:04.716 --> 17:13.645

[SPEAKER_00]: But when I interviewed her more recently, I had the wonderful opportunity for her to talk to me about her own early education growing up in Grenada, Mississippi,

17:13.625 --> 17:22.180

[SPEAKER_00]: and the way Negro history week was so central to her educational experiences in the 1940s and in early 1950s, right?

17:22.320 --> 17:31.937

[SPEAKER_00]: And then I started to think, you know, so many of the teachers that right at the school were black southern migrants from the south who had also experienced a similar kind of academic culture.

17:31.917 --> 17:52.686

[SPEAKER_00]: where black history and black literature were integral parts of the curriculum, even when it wasn't formally offered or prescribed by local school boards, but because these were black teachers who understood it to be important for the socialization and the academic development of the young, and they carry a lot of that over when it came to my educational experience.

17:53.067 --> 18:00.878

[SPEAKER_00]: And so I write, I bring these everyday ordinary teachers into the book because I see them as a part of

18:01.381 --> 18:05.487

[SPEAKER_00]: Negro history, we can Black History Month has been sustained for so long, right?

18:05.507 --> 18:08.392

[SPEAKER_00]: I talked about some of my college professors as well, right?

18:08.472 --> 18:13.640

[SPEAKER_00]: You know, who also grew up in the Jim Crow South, you know, became early Black studies professors, right?

18:13.780 --> 18:18.567

[SPEAKER_00]: Where Black studies in the university was not the first time they were introduced to these things, right?

18:18.587 --> 18:27.220

[SPEAKER_00]: Because many of them were demanding something that they knew existed because they have been introduced to it by teachers and other community members.

18:27.200 --> 18:30.785

[SPEAKER_00]: the various places that they came from in these segregated black communities, right?

18:31.146 --> 18:34.251

[SPEAKER_00]: I thought it was important to bring all those people into this story.

18:34.551 --> 18:53.359

[SPEAKER_00]: In addition to people like Carter G. Woodson and Mary McLeod, but do more recognizable figures because, you know, black history might dissomething that exists because of this kind of collective effort in black communities early on well before it's recognized by, you know, you know, government officials and president forward in 1976.

18:54.402 --> 19:01.033

[SPEAKER_02]: It's common this time of year in February to see a whole bunch of social media posts that are like black history as American history.

19:01.314 --> 19:05.862

[SPEAKER_02]: And you know, you talk in the book about how, you know, that's not quite it.

19:07.164 --> 19:08.747

[SPEAKER_02]: There's something more important here.

19:08.787 --> 19:10.770

[SPEAKER_02]: So could you expand upon that way?

19:10.991 --> 19:18.283

[SPEAKER_02]: What you mean by that and why it's not just like, we're adding some black important black figures to the narrative.

19:18.601 --> 19:19.042

[SPEAKER_00]: Yeah.

19:19.162 --> 19:19.523

[SPEAKER_00]: Thank you.

19:19.624 --> 19:20.546

[SPEAKER_00]: Thank you so much for that.

19:20.606 --> 19:23.273

[SPEAKER_00]: You know, I absolutely agree it every year.

19:23.353 --> 19:23.974

[SPEAKER_00]: We hear that.

19:24.015 --> 19:34.180

[SPEAKER_00]: We also hear, you know, we got the shortest month of the year and all this sort of stuff and and every time I hear that, you know, I I cringe a little bit because

19:34.160 --> 19:52.304

[SPEAKER_00]: you know, when people, and sometimes these are, you know, advocates are obviously advocates of, you know, studying black history, but it exposed to the fact that they, you know, for whatever reason haven't been invited to sit and think about the origins of how Black History Month came to be because no one gave us the shortest month of the year, right?

19:52.784 --> 19:57.210

[SPEAKER_00]: Because Black History Month is something that was created in black communities.

19:57.250 --> 20:01.956

[SPEAKER_00]: And it began as Negro History Week, and before that we have to think about Douglas Day,

20:01.936 --> 20:08.466

[SPEAKER_00]: in February that Mary Church to Real established in 1897, two years after Douglas passed the way.

20:08.506 --> 20:18.983

[SPEAKER_00]: That's the celebration of Douglas Day and the celebration of Lincoln's birthday in February is part of the reason that Carter G. Woodson chose the weekend's February that he did.

20:18.963 --> 20:37.663

[SPEAKER_00]: And so, when people say we got the shortest month of the year, they're participating in the erasure of the agency of people like Woodson, Black Stollers and Black Community members, who worked at a grassroots level to mobilize people to celebrate this, to create this early Black History movement that scholars write about.

20:38.124 --> 20:39.587

[SPEAKER_00]: To this other point,

20:39.567 --> 20:47.937

[SPEAKER_00]: I absolutely understand what people mean when they say black history is American history and it shouldn't be kind of, you know, taken out and only treated alone.

20:48.398 --> 20:57.589

[SPEAKER_00]: And I understand that absolutely black history and digitalist history need to be thought about as integral to thinking about the formation of the United States, right?

20:57.609 --> 21:08.022

[SPEAKER_00]: Because there is no way to think about the development of the nation without the way it developed through the disposition of black and

21:08.002 --> 21:14.271

[SPEAKER_00]: Part of what's in in these early black scholars who created Negro history week and black history much absolutely understood that.

21:14.974 --> 21:15.717

[SPEAKER_00]: However,

21:16.540 --> 21:20.306

[SPEAKER_00]: Black history is an integral part of American history, but it's not reducible to it.

21:20.746 --> 21:43.881

[SPEAKER_00]: And that's one of the things that I'm trying to lift up when I say that is that we can't contain Black history to only be about the United States because the early Black scholars of African American history understood that the kind of experiences of disposition and second class citizenship that Black people experienced in the United States was also connected to a much more broader African diasporic experience.

21:43.861 --> 21:57.530

[SPEAKER_00]: The Witcher Witch is why, when we go back to these early textbooks written by people like Carter G. Woodson, we look at the writing of people like the boys or, you know, Lila Amos Pendotin, she was a black woman's school teacher who published the textbook in 1912.

21:58.612 --> 22:02.781

[SPEAKER_00]: Before Woodson, they all integrate important elements.

22:02.761 --> 22:19.944

[SPEAKER_00]: of light history from the Caribbean and Latin America as well and also from the continent of Africa because they understood the way in which the disposition of black people and other parts around the world were also connected to the experience of anti-blackness and disposition that black people experience in the US.

22:20.324 --> 22:26.372

[SPEAKER_00]: And so a critical part of black history has always been about making these kind of international

22:26.352 --> 22:28.236

[SPEAKER_00]: links about the Black experience.

22:28.256 --> 22:41.445

[SPEAKER_00]: So when we say Black history of the American history, we leave it there, we're restricting the work that Black history is actually supposed to be doing when it comes to the kind of corrective work and the descriptive work about Black life as well.

22:41.465 --> 22:46.656

[SPEAKER_00]: And it requires much more broader understanding about Black life and in the Atlantic world.

22:47.513 --> 23:09.049

[SPEAKER_02]: One of the things I found really interesting about the development of Negro history week in what Carter Woods and was trying to do is that it's not just what we often see in especially elementary schools right now, which is like, now we're going to talk about me, Jamison, but it's actually trying to talk about the everyday experiences of black people and

23:09.029 --> 23:17.097

[SPEAKER_02]: You know, I wonder if you could talk a little bit more about that, that's kind of the whole point of this podcast is, you know, who, who, who, what are the people we don't know a lot about?

23:17.157 --> 23:19.719

[SPEAKER_02]: What are the experiences that, that we haven't heard more about?

23:20.199 --> 23:27.166

[SPEAKER_02]: So, what did that look like in what Carter, what some was trying to do, and what does that continue to look like through the present day?

23:27.186 --> 23:36.775

[SPEAKER_00]: Yeah, but I think about that question, I think about who Carter G. Woodson was at the

23:36.890 --> 23:54.527

[SPEAKER_00]: part of his motivations for building and fighting to kind of create a field of, you know, Negro history now, black and African American history that we have today is that, you know, Carter G. Woodson's trajectory into kind of, you know, academic scholarship.

23:54.507 --> 24:01.578

[SPEAKER_00]: is not the typical trajectory that we think of when we think of early 20th century important scholars in the academy.

24:02.319 --> 24:05.584

[SPEAKER_00]: Part of what's in was the child in student of formerly enslaved people.

24:05.985 --> 24:08.769

[SPEAKER_00]: And I intentionally say student also, right?

24:09.049 --> 24:14.137

[SPEAKER_00]: His first teachers in a one-room schoolhouse where his formerly enslaved uncles, right?

24:14.438 --> 24:21.308

[SPEAKER_00]: And he learned early on, even when it was not written in formal curriculum, he learned

24:21.288 --> 24:26.214

[SPEAKER_00]: through oral traditions about the experiences of his mother and his families enslaved.

24:26.234 --> 24:31.280

[SPEAKER_00]: And he learned from his uncles at the age of 20 years old, right?

24:31.640 --> 24:35.725

[SPEAKER_00]: Would go to a school in Huntington, West Virginia, called the Frederick Douglass School, right?

24:35.745 --> 24:45.757

[SPEAKER_00]: There's the high school he attended, the naming of the school itself, you know, suggests the kind of learning objectives and commitments that the teachers at this school would have.

24:45.777 --> 24:50.603

[SPEAKER_00]: And we know this for a fact also because the principle of that school,

24:50.583 --> 25:14.025

[SPEAKER_00]: was eventually fired because of views that he expressed in a local black newspaper and Huntington West Virginia, part of what's in also worked in the coal mines alongside illiterate civil war veterans and he talks about how these men who were illiterate would pay him in the evenings to read to them from newspapers from books that they themselves could not interpret, you know, could not decipher and read.

25:14.005 --> 25:24.000

[SPEAKER_00]: but they can't, but they wanted to interact with the literary world and he was their opportunity for them to do that and they were speaking back to these written texts about things that were being left out.

25:24.040 --> 25:39.945

[SPEAKER_00]: And so he became formed through these kind of stories about Black History such that when he went to a place like the University of Chicago and then ultimately to Harvard where he gained his PhD in 1912,

25:39.925 --> 25:48.081

[SPEAKER_00]: where his professors told him that there was no such thing as black history or our culture, or at least not worthy of respect in study, right?

25:48.301 --> 26:00.364

[SPEAKER_00]: He had all of this evidence from these communities that he had worked and operated in, that he had been shaped and cultivated in, that gave him the confidence to insist that

26:00.344 --> 26:09.032

[SPEAKER_00]: Black history was a legitimate field of study, and that it needed to be studied in order to understand the United States better and to understand the modern world better, right?

26:09.432 --> 26:12.975

[SPEAKER_00]: I say all that to say that those were ordinary people, right?

26:13.075 --> 26:23.364

[SPEAKER_00]: Who were, who carried on this legacy of Black memories and Black historical knowledge, even when it was not respected in the context of the academy.

26:23.684 --> 26:30.250

[SPEAKER_00]: So, Carter, you would always knew that we had to be much more expansive in terms of where we look,

26:30.230 --> 26:42.988

[SPEAKER_00]: for meaningful history, for meaningful sources of history to inform our historical scholarship, and he modeled this throughout the work that he did, and this also carried over to how he invited people to celebrate Negro history week.

26:43.329 --> 26:55.967

[SPEAKER_00]: He didn't just say hold up the stories of prominent, you know, men and women of black history, that was important, but he also invited people to say, looking at your local communities for things that have not been studied.

26:55.947 --> 26:57.488

[SPEAKER_00]: and write to us about them.

26:57.909 --> 27:04.455

[SPEAKER_00]: Find ways to organize in your local community to bring people in to be able to talk about things about local history.

27:04.535 --> 27:13.323

[SPEAKER_00]: Find ways to organize to preserve sources so that they can continue to be studied because we need these things in order to continue to expand and build the field.

27:13.643 --> 27:18.147

[SPEAKER_00]: So black history and black history commemorations with the action-oriented project.

27:18.647 --> 27:23.592

[SPEAKER_00]: It wasn't just about watching good films and eating good food, right?

27:24.473 --> 27:25.954

[SPEAKER_00]: Which is,

27:25.934 --> 27:43.865

[SPEAKER_00]: I think there are a lot of opportunities for people to rethink how they participate in black history commemorations because there is so much work still to be done when it comes to preservation, on covering important historical narratives and local history and beyond, right that we don't really hear about.

27:44.185 --> 27:49.113

[SPEAKER_00]: There's a lot of work that needs to be done to help us understand familiar figures and unfamiliar ways, right?

27:49.154 --> 27:50.035

[SPEAKER_00]: Because we've

27:50.015 --> 27:55.985

[SPEAKER_00]: Austin got into the habit of teaching about particular individuals in black history in very sanitized ways.

27:56.827 --> 28:10.690

[SPEAKER_00]: And so I think that's one of the things I wanted to introduce in the book is to demonstrate all these ways that people were using early Negro history week in black history on programs in ways to contribute to the like

28:10.670 --> 28:13.193

[SPEAKER_00]: to the tradition, not just observe it, right?

28:13.213 --> 28:14.855

[SPEAKER_00]: It's not just an observance, right?

28:14.875 --> 28:22.966

[SPEAKER_00]: But it's an invitation to participate in the work and the labor that's required to maintain something like this for a century and beyond.

28:23.667 --> 28:25.930

[SPEAKER_02]: So let's talk about some of that labor then.

28:26.010 --> 28:39.327

[SPEAKER_02]: You yourself are part of the black teachers, archive, and there's a lot of work, as you mentioned, that still to be done in terms of making sure that both physical archives don't get physical,

28:39.307 --> 28:44.037

[SPEAKER_02]: pieces of history that can get into an archive aren't lost.

28:44.438 --> 28:46.021

[SPEAKER_02]: Oral histories aren't lost.

28:46.322 --> 28:55.020

[SPEAKER_02]: So talk some about not just what was done in the past, but what's being done today to ensure the future of Black History.

28:55.878 --> 29:11.836

[SPEAKER_00]: Yeah, you know, there's, there's a lot of work that's being done, and in, and some of that work is being challenged when we think about the kind of current funding landscape, which is also part of the reason why I think it's important for people to understand the role that they can play to continue to help supporting this work.

29:12.217 --> 29:22.729

[SPEAKER_00]: But you know, I think about wonderful projects like the Color Prevention Project that the Gabrielle Fwerman has done and is continuing to do preserving this important rich political

29:22.709 --> 29:46.000

[SPEAKER_00]: history and organizing work that Black folks did, Black men and women did in the 19th century with these color conventions where they were organizing around important issues with then Black communities and institution building in order to create networks to kind of advocate for the rights of Black people and to try to push for this kind of social transformation that was necessary for the more

29:45.980 --> 29:56.660

[SPEAKER_00]: You know, the fuller inclusion of black folks, but the black teacher archive is a project that's also that's inspired by that kind of rich kind of digital humanities work that had recently been done.

29:56.700 --> 30:05.878

[SPEAKER_00]: So just to give a little bit of backstory that I was working on my first book and working to document Carter G. Woodson's partnership with black teachers nationally.

30:05.858 --> 30:16.671

[SPEAKER_00]: I started to realize that these formalized networks called color teacher associations that existed across all of the kind of former confederate states and some of the border states as well.

30:17.212 --> 30:30.769

[SPEAKER_00]: And a couple of states in the north also these were black teacher professional organizations that existed because black teachers had historically been excluded from the professional organizations that that white teachers were in.

30:30.749 --> 30:59.457

[SPEAKER_00]: It was through these formalized institutions that things like Negro history, textbooks written by Carter G. Woodson, information written by people like Du Bois, were able to circulate because people like Vermicell Petone was the president of this national coalition of all of these organizations and they were in partnership and they were able to disseminate this information around the country in a very efficient way because of this kind of

30:59.437 --> 31:02.121

[SPEAKER_00]: kind of black and networked black segregated world.

31:02.722 --> 31:09.873

[SPEAKER_00]: But when I was trying to find the records of these color teacher associations, I found that to be more challenging than I expected.

31:10.774 --> 31:15.842

[SPEAKER_00]: And I started to realize that the journals, the serial publications,

31:15.822 --> 31:25.077

[SPEAKER_00]: of color teacher association, so like, you know, the Louisiana color teachers association, the, you know, the Tennessee association of teachers in Negro schools, right?

31:25.437 --> 31:39.079

[SPEAKER_00]: They have various different names across states, but they had regular, quarterly meetings, right, and statewide meetings, and district meetings, and they kept lots of records, and they also published journals to disseminate information.

31:39.059 --> 31:52.074

[SPEAKER_00]: And I will think what to find, lots of early coverage of Black History and Negro History Week celebrations in local school communities being encouraged through the leadership of these Black teachers.

31:52.615 --> 31:55.178

[SPEAKER_00]: But finding the records were difficult.

31:55.378 --> 31:57.560

[SPEAKER_00]: Some of them existed in bits and pieces.

31:57.961 --> 32:02.406

[SPEAKER_00]: Some of them were scattered and various individuals, kind of their personal papers.

32:02.927 --> 32:04.088

[SPEAKER_00]: Sometimes,

32:04.068 --> 32:17.839

[SPEAKER_00]: I was told that, you know, certain places didn't have the records, but law and behold, they were in the archive found a way, but like unprocessed and inaccessible and unsearchable, we kind of search through kind of library databases and things like that.

32:18.240 --> 32:22.650

[SPEAKER_00]: And this was for me a realization that this is how

32:22.630 --> 32:49.684

[SPEAKER_00]: This is contributed to the erasure of black teachers and the role that they played in the black freedom struggle and we haven't really been able to appreciate the role that this networked world of black educators played in shaping so many generations of black leaders so myself and my colleague Emani Perry who also use these records for her book on the black national anthem decided to come together and work to seek out you know all of the journals that still exist in bits and pieces in different places.

32:49.664 --> 33:00.943

[SPEAKER_00]: catalog them and make them available digitally so that we can continue to kind of revise the narrative about this aspect of black educational history and asking American history in the 19th and 20th century.

33:01.684 --> 33:05.631

[SPEAKER_00]: And that's a part of how I've been able to kind of recover and write about.

33:05.611 --> 33:22.675

[SPEAKER_00]: This very early rich story of Negro History Week and the work that everyday black teachers played and spreading it because I'm able to trace it across this more than 50,000 pages of written material by black teachers representing their kind of professional associations in ways that we haven't had access to before.

33:23.718 --> 33:33.828

[SPEAKER_02]: You've also been working with high school students and helping them see this study of black history as not just passive, but an active process.

33:34.068 --> 33:46.420

[SPEAKER_02]: Could you reflex them up on that and what maybe we should be doing more in schools largely to tell people understand this active process of memory keeping in black history?

33:46.460 --> 33:49.843

[SPEAKER_00]: Yeah, thank you for that.

33:50.785 --> 33:57.013

[SPEAKER_00]: I've been working with a group of high school students in the Long Beach 75 school district for about three years now.

33:57.855 --> 34:03.262

[SPEAKER_00]: And these are students who decided to form a district wide black literary society.

34:03.643 --> 34:13.536

[SPEAKER_00]: Similar to how black student unions work, but they created this one to be kind of not just as face for kind of social, emotional, development, and support, but also based in

34:13.516 --> 34:24.929

[SPEAKER_00]: reading and study of black literature, and that's relevant to their experience as black students, but that's also connected to skills needed for success in core subject areas, right?

34:25.470 --> 34:34.420

[SPEAKER_00]: And so this began with them reading my previous book, School Clothes, which is about black student experiences in the American School, using sources that prioritize black student voices.

34:35.161 --> 34:41.008

[SPEAKER_00]: And when talking with them about this, the book, and various occasions,

34:40.988 --> 34:58.436

[SPEAKER_00]: Just hearing them respond in terms of what they gained from the book, what they gained from their studies in this black literary society versus what they did not get in black history education in their traditional curriculum, they expose a lot of things like, you know, they never talked about slavery outside of the south.

34:58.457 --> 35:00.600

[SPEAKER_00]: So the nears, the parts of the narrative in the book.

35:00.580 --> 35:18.165

[SPEAKER_00]: where they're learning about these early histories of kind of, you know, of slavery and in the north, or the capture of fugitive slaves in the north and sending them back south, we're thinking that that troubled the way that they had been taught to think about this part of history, right?

35:18.506 --> 35:26.858

[SPEAKER_00]: So, so they're both exposing some of the limitations and in some of in terms of way black history is taught in schools, but then they also talked about the fact,

35:26.838 --> 35:36.970

[SPEAKER_00]: that rarely did they learn anything about historical figures from the 19th century other than maybe occasional references to Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman, of course, right?

35:37.030 --> 35:54.651

[SPEAKER_00]: But so learning about people like Charlotte Fordon or learning stories about Alexander Krummel and Henry Highland Gardenet, they were like, this is it was like stretching their imagination in ways that they started to call out and notice the absences.

35:54.631 --> 35:57.635

[SPEAKER_00]: and the history, the black history that they were being taught.

35:58.136 --> 36:14.379

[SPEAKER_00]: But then when they started to learn about the black teacher archives, you know, they also talked about the fact that they didn't know what an archive was that in all of their education and social studies in history, they had never been invited to think about the production of history, right?

36:14.620 --> 36:16.943

[SPEAKER_00]: But more so had just been taught

36:16.923 --> 36:29.922

[SPEAKER_00]: names, dates, and events, which are, it's important to study those things, but it's also important to invite students to think about how we know what we know about particular people and particular events in history.

36:30.423 --> 36:38.675

[SPEAKER_00]: To give them the resources to think, to be critical and vigilant kind of consumers of history and not just passive consumers of history.

36:39.376 --> 36:46.626

[SPEAKER_00]: And it also led to them naming the fact that they don't know anything about the local history and the cities that they live in,

36:46.606 --> 36:51.817

[SPEAKER_00]: So they decided, you know, that, so we've been working to do this kind of local Black History project.

36:51.837 --> 36:53.801

[SPEAKER_00]: That's an inquiry-based project that they're leading.

36:54.162 --> 37:03.602

[SPEAKER_00]: A lot of it is focused on local Black educational history in the city that they live in, but doing things like going back and look and analyzing early school year books of the schools that they're at.

37:03.582 --> 37:14.392

[SPEAKER_00]: looking at local newspapers for coverage of various different events thinking about how you know desegregation efforts were similar or different to other cities in the state and other parts of the country.

37:14.733 --> 37:19.566

[SPEAKER_00]: Those kinds of questions that they just had never been invited to think about.

37:19.985 --> 37:48.827

[SPEAKER_00]: Yeah, that's I think those are some of the things that I think we need to get back to doing are start doing when it comes to the way we commemorate Black History Month and the way that we integrate Black History into our curriculums year-round and working with these young people have helped me think in a lot more practical ways about some very clear things that can be done to reshape people's exposure and education when it comes to Black History.

37:49.330 --> 38:11.061

[SPEAKER_00]: You know, the fact that everyone knows Black History Month, but it's supposed to know one knows anything about Carter G. Woodson, is also evidence of the fact that every year people are encouraged to do something about Black History Month, some sort of observance, but they're not taught about why something like Black History Month came to be in the first place.

38:11.081 --> 38:18.612

[SPEAKER_00]: Because there's no way of teaching that without having to think about the struggles that some of my Carter G. Woodson

38:18.592 --> 38:39.267

[SPEAKER_00]: in developing it in the first place right so there was a national poll that just happened within the past couple of months ahead of this anniversary it was a national sampling of thousands of people and there were acts identified a various figures in black history if they learned anything significant about this person and their educational journey learned a little bit so on and so forth.

38:39.247 --> 38:48.577

[SPEAKER_00]: That's at a percent of the people that were that were pulled said that they recognize Carter J. Woodson's name or it learned anything significant about him in school, right?

38:48.958 --> 39:02.132

[SPEAKER_00]: That exposes the very thin engagement with the Black Historical Tradition that students are being exposed to in school that they can recognize so many people can everyone can recognize Black History Month in the U.S. and around the world.

39:02.112 --> 39:14.807

[SPEAKER_00]: But no, so little about Carter G. Woodson, and that exposes the fact that they're not learning about the what's politically at stake in something like Negro history week in Black Kishima because you can't appreciate that without understanding its origin story.

39:16.089 --> 39:31.427

[SPEAKER_02]: We're talking, of course, at a time of a lot of legal challenges to the teaching of Black history and lots of other critical history and I've seen various people on social media say, well, we got to go read a fugitive pedagogy for.

39:31.407 --> 39:34.292

[SPEAKER_02]: to learn how we can push back.

39:34.372 --> 39:50.277

[SPEAKER_02]: I wonder, are there lessons that we can learn from the past from the people who were challenging up against what was going on at society to try to teach important history, things that we might be able to sort of take into the future?

39:51.573 --> 39:51.893

[SPEAKER_00]: Yeah.

39:52.554 --> 39:52.874

[SPEAKER_00]: Absolutely.

39:52.914 --> 39:58.619

[SPEAKER_00]: I think one of the important lessons is that we have to realize that we have to fight this battle on multiple fronts.

39:59.220 --> 40:16.976

[SPEAKER_00]: That is has to happen that we have to continue to push to make sure that it's formally included and and and and truthful and honest ways and in the kind of curriculum in schools, right, because that's necessary for thinking about the democratic project of public schooling, right.

40:17.196 --> 40:21.580

[SPEAKER_00]: But we also have to make sure that we're

40:21.560 --> 40:38.387

[SPEAKER_00]: to make sure that even in the absence of kind of critical engagement in school that we're kind of still working and struggling there, that this information is being made available in community spaces and community education spaces and organizing spaces, and that we think about education in a much more broader.

40:38.367 --> 40:57.253

[SPEAKER_00]: in a much broader way, right in a much more expansive way because that's the only way we can kind of organize effectively around this project is when we invite people to understand that even if you yourself are not a historian at a university or a history teacher, history is something that has implications for all of our

40:57.233 --> 40:58.334

[SPEAKER_00]: all of our lives, right?

40:58.875 --> 41:12.132

[SPEAKER_00]: All of us are working with and thinking with historical scripts and more making decisions about who we are, how we identify, how we make sense of the world that we're living in, right, consciously and unconsciously, right?

41:12.152 --> 41:23.967

[SPEAKER_00]: And so we have to, we have to all cultivate a mature historical consciousness and that's something that the early Black History movement that led to the creation of Negro History Week did

41:23.947 --> 41:38.100

[SPEAKER_00]: everyday community members, right, people who were leading community institutions to understand that there was a connection between how we understand and remember the past and the way in which we understand our present lives and the world that we share today.

41:38.380 --> 41:50.832

[SPEAKER_00]: And history is one of the most important resources for thinking about what's the most effective ways of pursuing justice in the future to not kind of repeat certain harms that we have perpetuated in the past.

41:50.812 --> 41:56.980

[SPEAKER_00]: And, you know, Cardi G. Woodson has a very important line when he says there would be no lynching if he did not start in the school room, right?

41:57.000 --> 42:16.144

[SPEAKER_00]: And in the misjudication of the Negro, and I always read that line from Woodson to mean that he's making this very clear connection to the kind of social problems in the world that we live in today, as always connected with the scripts of history and literature and the kind of curricular foundation of schooling that shapes

42:16.124 --> 42:22.213

[SPEAKER_00]: All of our identities because we're all initiated into the world that we live in through schooling in some way, right?

42:22.513 --> 42:30.084

[SPEAKER_00]: And history is always at the foundation of that curriculum, even if you are not a formal historian or a formal history teacher.

42:30.144 --> 42:37.595

[SPEAKER_00]: And so we all have to understand what sets what's politically at stake and honest accounts of the past because it has implications for all of our lives.

42:38.897 --> 42:42.182

[SPEAKER_02]: I would love to encourage listeners to read your book.

42:42.382 --> 42:44.325

[SPEAKER_02]: Can you tell them how they can get a copy?

42:44.930 --> 42:45.611

[SPEAKER_00]: Absolutely.

42:46.112 --> 42:59.338

[SPEAKER_00]: So you can find a copy of I'll make me a world, the 100 year journey of Black History Month at any and all of your local independent bookstores, like to support independent bookstores and any major seller, you know, bookseller online as well.

42:59.378 --> 43:01.742

[SPEAKER_00]: You can also get a copy of the book there.

43:01.762 --> 43:04.828

[SPEAKER_00]: But I highly encourage you to support local bookstores.

43:05.247 --> 43:10.795

[SPEAKER_02]: Definitely, and if you're listening to this after Black History Month as past, you can still read about Black History Month.

43:10.815 --> 43:11.396

[SPEAKER_00]: Absolutely.

43:12.017 --> 43:15.402

[SPEAKER_00]: Yeah, one of the organizations I'm working with, Campaign Zero.

43:15.802 --> 43:25.737

[SPEAKER_00]: We've been doing a lot of work engaging teachers around the book this month, but then, you know, given that this is the 100th anniversary after February, there's going to be this, keep it 100 campaign.

43:25.717 --> 43:46.323

[SPEAKER_00]: to continue this conversation, especially as we think about the 250 of celebrations for American independence, because I think there's a really important conversation to be had about those commemorations that are coming up and the way in which this history of Black History Month needs to be in dialogue with that particular history and those celebration as well.

43:47.184 --> 43:47.465

[SPEAKER_02]: Great.

43:47.885 --> 43:50.308

[SPEAKER_02]: Jarvis, thank you so much for speaking with me.

43:50.549 --> 43:55.555

[SPEAKER_02]: I love reading this book and

44:04.057 --> 44:27.195

[UNKNOWN]: Thank you.

44:31.023 --> 44:47.327

[SPEAKER_04]: Lift every voice and sing Till art that heaven ring Ring with the harp on me

44:50.969 --> 45:11.155

[SPEAKER_04]: But in that our rejoicing runs high as the listening scans, that it resounds out as the rolling seas.

45:15.117 --> 45:31.725

[SPEAKER_05]: the song, full of the faith that the darkness has taught us, sing a song, full of the hope that the present has brought.

45:36.987 --> 46:03.889

[SPEAKER_04]: Facing the rising sun of a new day be gone Let us march on to victory Is one

46:07.733 --> 46:14.683

[SPEAKER_01]: Thanks for listening to Unsung History!

46:15.484 --> 46:19.009

[SPEAKER_01]: Please subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app.

46:19.490 --> 46:24.978

[SPEAKER_01]: You can find the sources used for this episode in a full episode transcript at unsunghistorypodcast.com.

46:25.599 --> 46:36.154

[SPEAKER_01]: To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain, or are used with permission.

46:36.505 --> 46:39.414

[SPEAKER_01]: or on Facebook at unsung history podcast.

46:39.434 --> 46:43.086

[SPEAKER_01]: The contact is with questions, corrections, praise, or episode suggestions.

46:43.548 --> 46:46.076

[SPEAKER_01]: Please email Kelley at unsung historypodcast.com.

46:46.838 --> 46:50.811

[SPEAKER_01]: If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate, review, and tell everyone you know.

46:51.152 --> 46:51.493

[SPEAKER_01]: Bye.